COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS INITIATIVES

Overview

A range of projects related to climate change adaptation are currently underway across the state of Massachusetts. Benefiting from a general political consensus in support of climate change planning, the state-level government has been able to harness and mobilize the financial resources necessary to begin confronting climate threats across the commonwealth. While these initiatives do not address the full range of ecologies and communities under threat, they nevertheless traverse a diverse range of landscapes and contexts. Additionally, many of the initiatives underway pay particular attention to the complexities of adapting landscapes imbued with ‘cultural significance.’ This fact makes MA a particularly interesting case study in how climate planning and design can, and should, intersect with questions of history, justice, and equity.

The four case studies included here exemplify long term planning for coastal and inland flooding, water quality, carbon uptake and energy production. While each project directly addresses the limitations of ambitious infrastructure projects throughout Massachusetts’ history, such as landfilling and dam building, they fail to fully confront past injustice. While indigenous and marginalized communities fight to bring histories of displacement, erasure, and disinvestment into the climate planning conversation, the current occlusion of these histories of injustice from the planning and design process risks their replication today.

• Changes to the Land, Harvard Forest

• Tidmarsh Wildlife Sanctuary

• Charles River Flood Control

• Climate Ready Boston

The four case studies included here exemplify long term planning for coastal and inland flooding, water quality, carbon uptake and energy production. While each project directly addresses the limitations of ambitious infrastructure projects throughout Massachusetts’ history, such as landfilling and dam building, they fail to fully confront past injustice. While indigenous and marginalized communities fight to bring histories of displacement, erasure, and disinvestment into the climate planning conversation, the current occlusion of these histories of injustice from the planning and design process risks their replication today.

• Changes to the Land, Harvard Forest

• Tidmarsh Wildlife Sanctuary

• Charles River Flood Control

• Climate Ready Boston

Organizations

Changes to the Land:

• Harvard Forest

• Harvard University

Charles River Flood Control:

• United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE)

• Charles River Conservancy

Tidmarsh:

• MIT Media Lab

• Interfluve

• Cape Cod Cranberry Grower’s Association

• Harvard Forest

• Harvard University

Charles River Flood Control:

• United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE)

• Charles River Conservancy

Tidmarsh:

• MIT Media Lab

• Interfluve

• Cape Cod Cranberry Grower’s Association

Climate Ready Boston:

• City of Boston

• Massachusetts Audubon Society

• Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) • Sasaki

• Halvorson | Tighe & Bond

• Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA)

• Boston Research Advisory Group (BRAG)

• W.D. Cowls, Inc.

• City of Cambridge

• City of Boston

• Massachusetts Audubon Society

• Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) • Sasaki

• Halvorson | Tighe & Bond

• Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA)

• Boston Research Advisory Group (BRAG)

• W.D. Cowls, Inc.

• City of Cambridge

Key Terms

CLIMATE IN CONTEXT

Contact between Native and non-Native people is often seen as a singular event at a particular point in time. Contact is in fact an ever occurring experience between those surviving indigenous peoples in a place and those who continue to arrive and settle within and around indigenous communities.

- Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe

Ecosystems, Ownership, and Climate

15,000 years ago, the Wisconsin Glacier receded, revealing the land which now makes up the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Since that time, the land has been variously inhabited, occupied, and colonized - first by indiginous peoples, then English colonizers (the pilgrims in 1620), and later, groups emigrating from across the world. Today, Massachusetts is divided into federal, state and municipal jurisdictions, few of which follow ecosystem boundaries.

The four climate change projects included in this dossier range in scale and scope, as well as the key climate challenges they tackle. Climate Ready Boston focuses mainly on coastal sea level rise and storm surge; Tidmarsh Farm and Charles River Watershed Project focus on inland flooding; and Harvard Forest’s Changes to the Land looks at statewide land use issues. While separated geographically, these four projects illustrate the reciprocal effects of climate change, in which coastal hurricanes can affect inland flooding, and upstream marshes can protect downstream urban areas.

MASSACHUSETTS TIMELINE

CHANGES TO THE LAND

Harvard Forest

Harvard Forest is a research forest located in Petersham, Massachusetts, owned and operated by Harvard University since 1907. At its founding, Harvard Forest was meant to serve as a field laboratory for students, a research center in forestry and related disciplines, and a demonstration site for sustainable forestry.

In 1914, Harvard Forest was made a graduate school for students studying forestry, which later moved to the Faculty of Arts and Sciences in 1932. In 1915, Harvard Forest changed its mission to serve as an example to the local community of the care and marketing of forests. Today, the Forest focuses on interdisciplinary research and educational programs that investigate the ways in which physical, biological and human systems interact to change the earth.

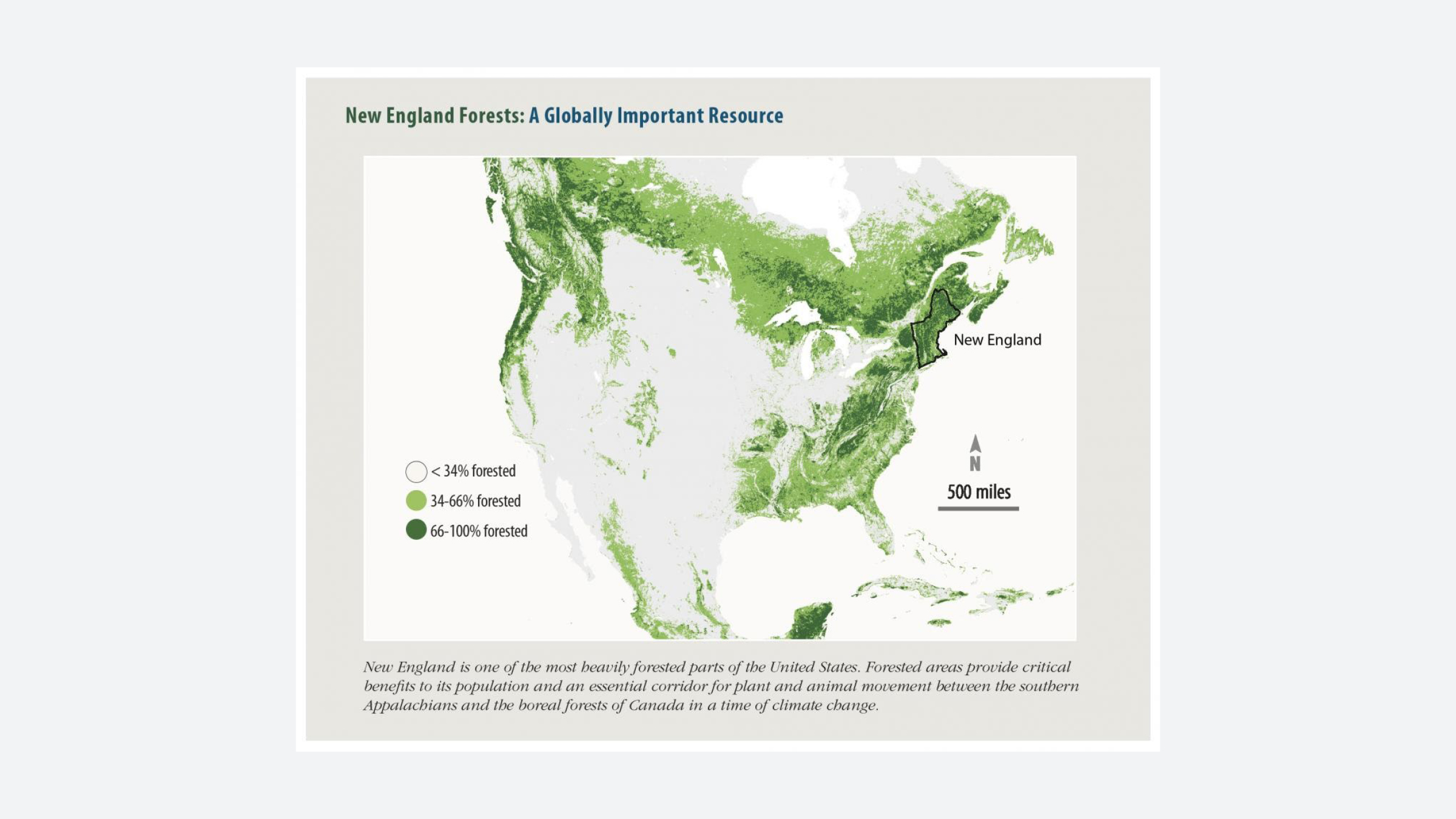

The Forest is a resource that enables long-term study of botanic biodiversity, composition and growth across generations, and offers experimental plots to test scientific hypotheses about species composition across the broader New England area. In 2014, Harvard Forest published “Changes to the Land: Four Scenarios for the Future of the Massachusetts Landscape,” a detailed study of risks and opportunities related to conservation and development within the state as part of their ongoing Wildlands and Woodlands initiative.

Wildlands and Woodlands

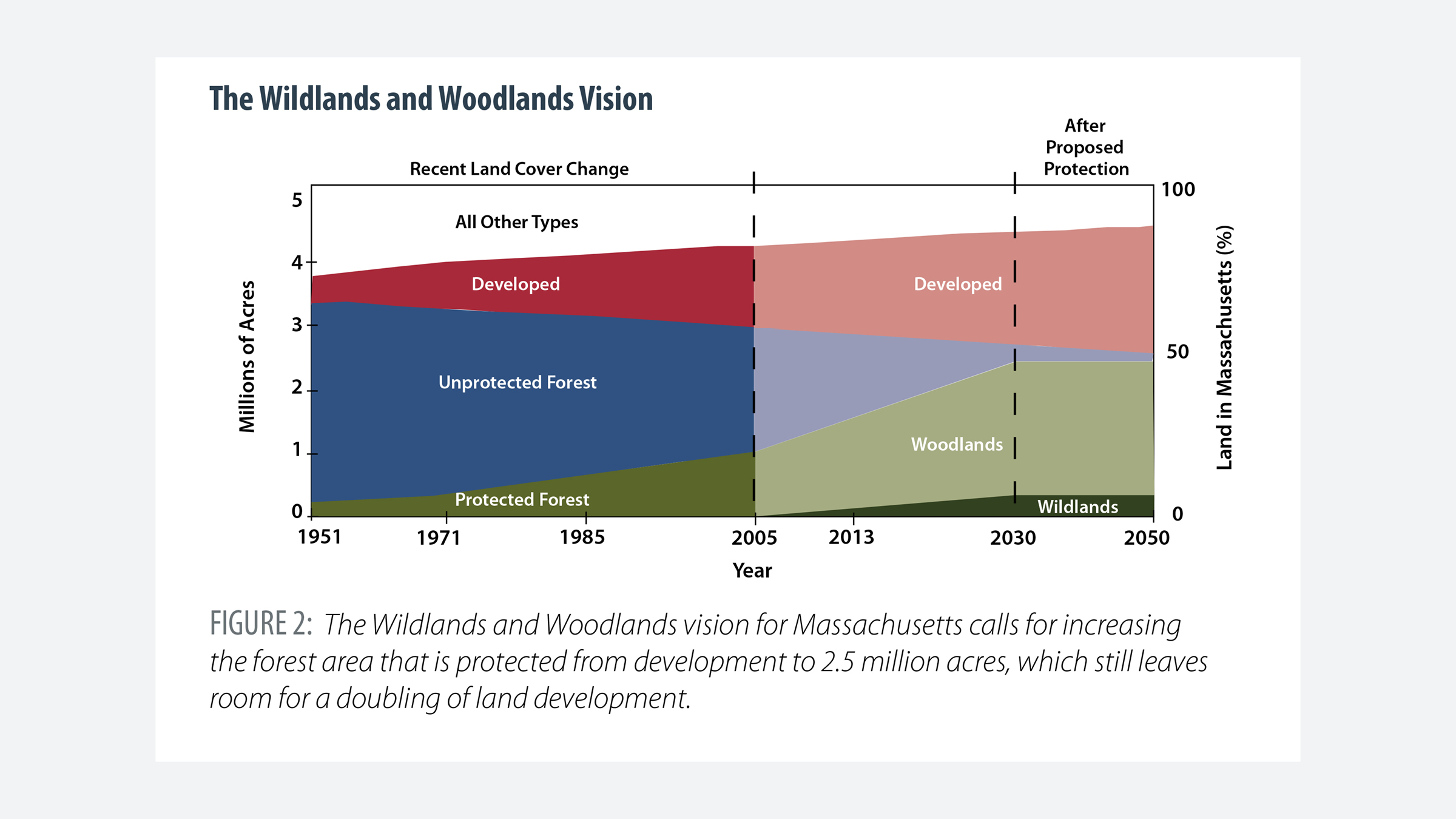

In its 2005 publication Wildlands and Woodlands: A Vision for the Forests of Massachusetts in 2005, Harvard Forest calls for the conservation of half of the Commonwealth as forestland, drawing on the strong tradition of private land-ownership in the state which began with colonization in 1620. The initiative is proposed as a 50-year conservation effort that also includes preserving 7% of New England as farmland.

Wildlands and Woodlands examines land cover change, using large-scale GIS mapping to identify existing forest blocks and potential wildland reserves in four key areas in southeastern, central and western Massachusetts. The resulting proposal calls for the state to protect 2.4 million acres from development, while also allowing for the amount of land development in Massachusetts to double. The publication notes that New England loses forestland at a rate of 65 acres per day to development, and public funding for land protection has declined since 2008.

Since its initial publication, the Wildlands and Woodlands vision has been updated and republished twice, once in 2010 and again in 2017 by scientists, conservations, urban planning experts, and environmental historians.

Changes to the Land

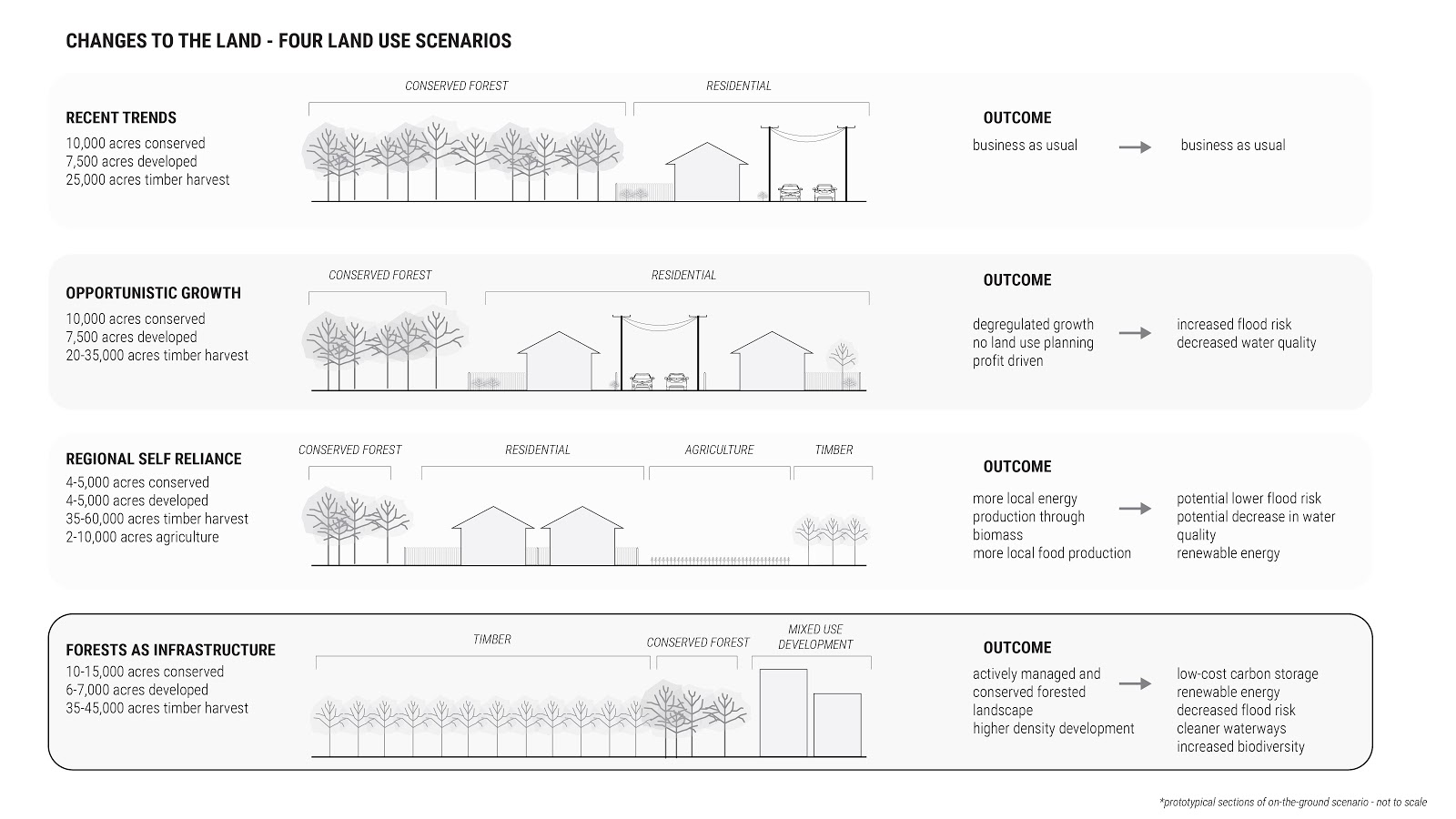

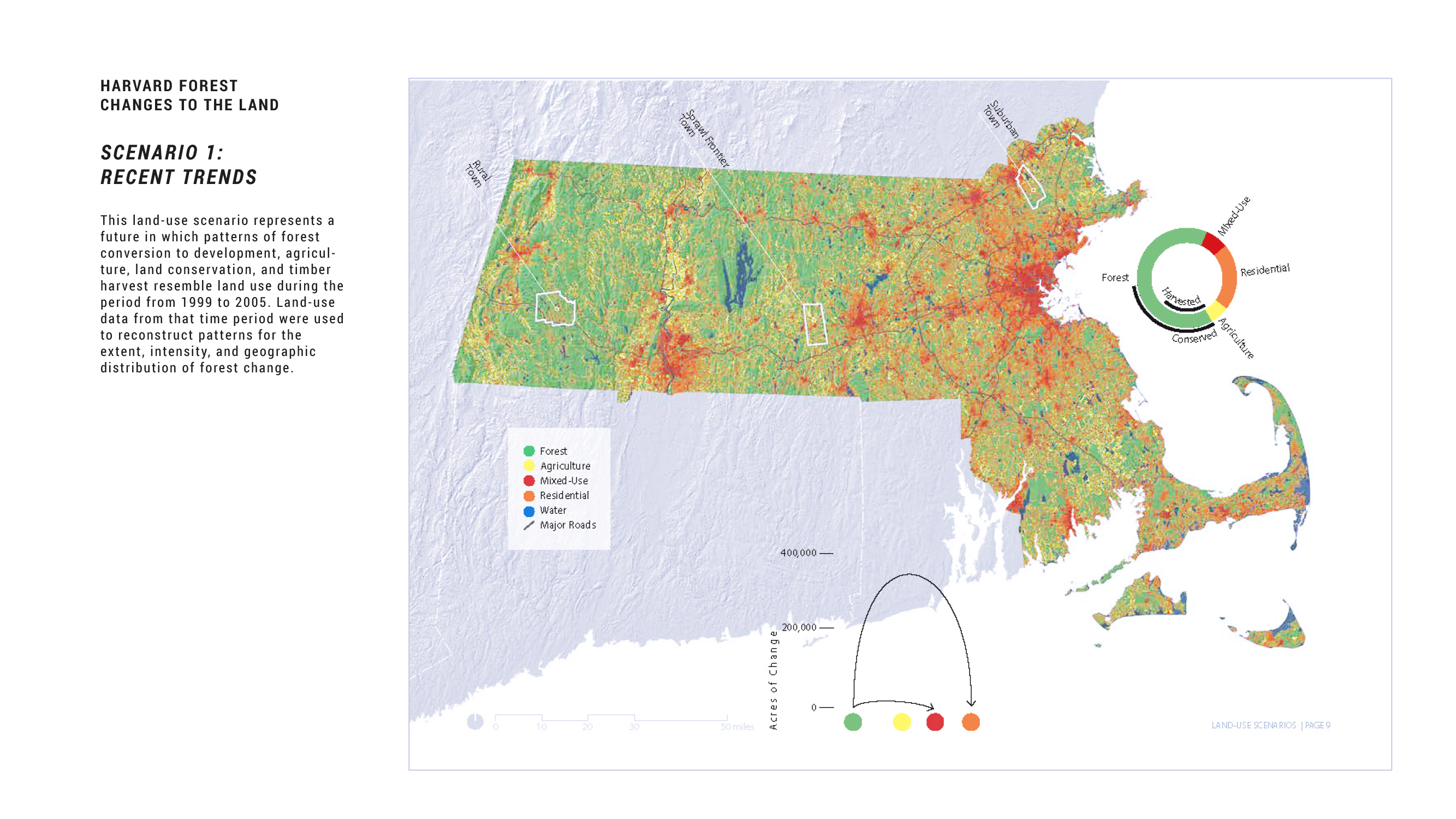

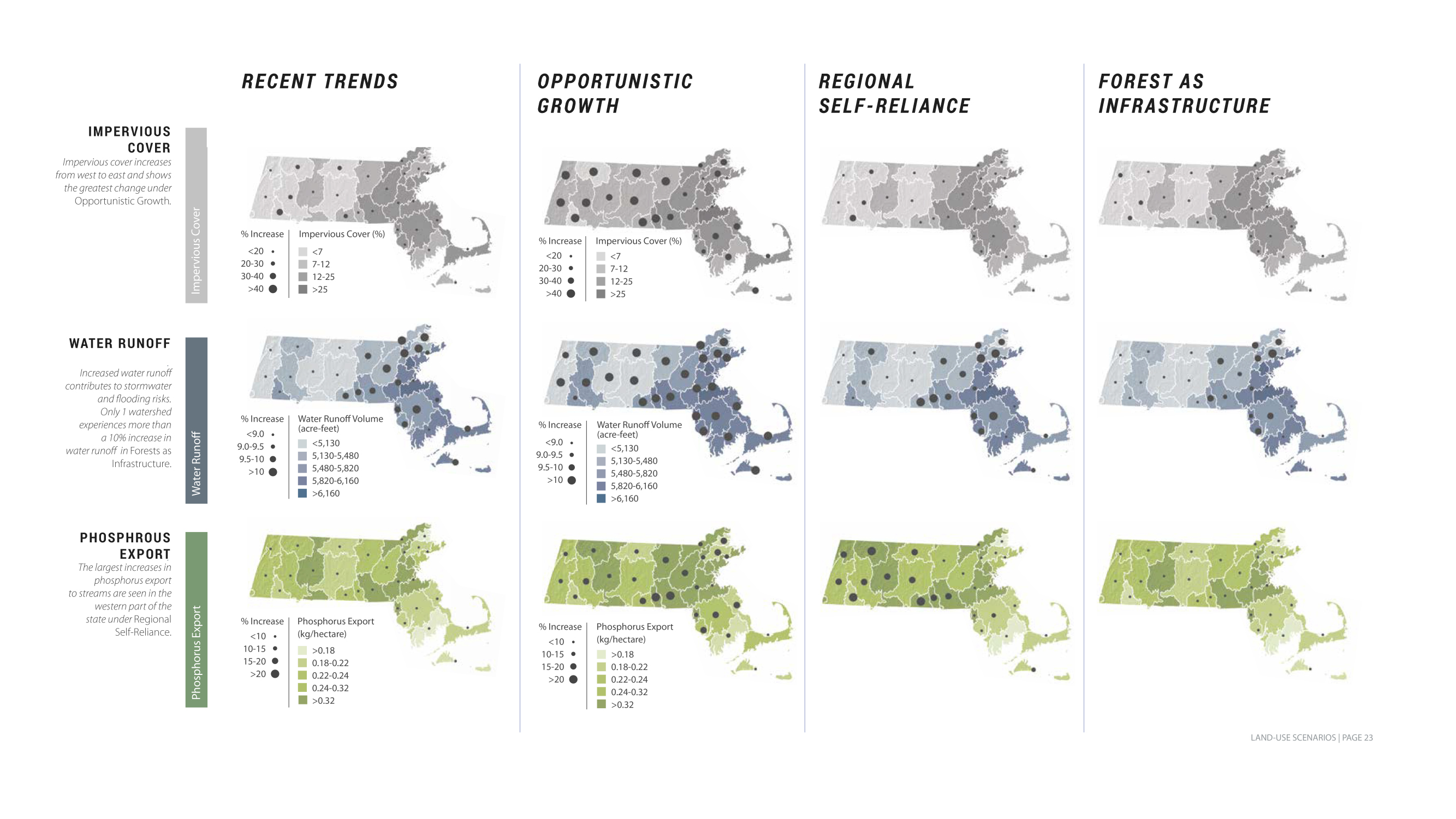

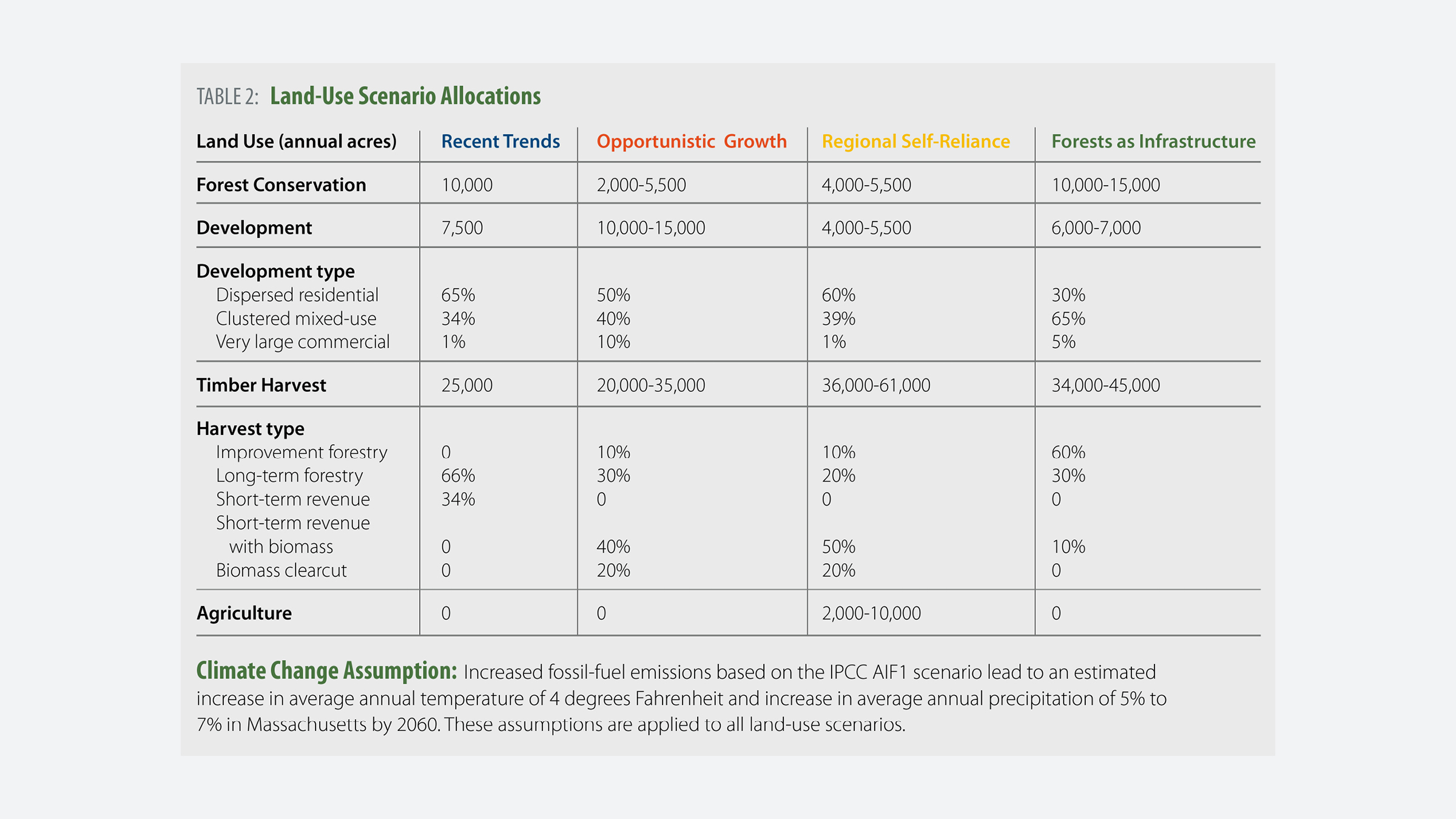

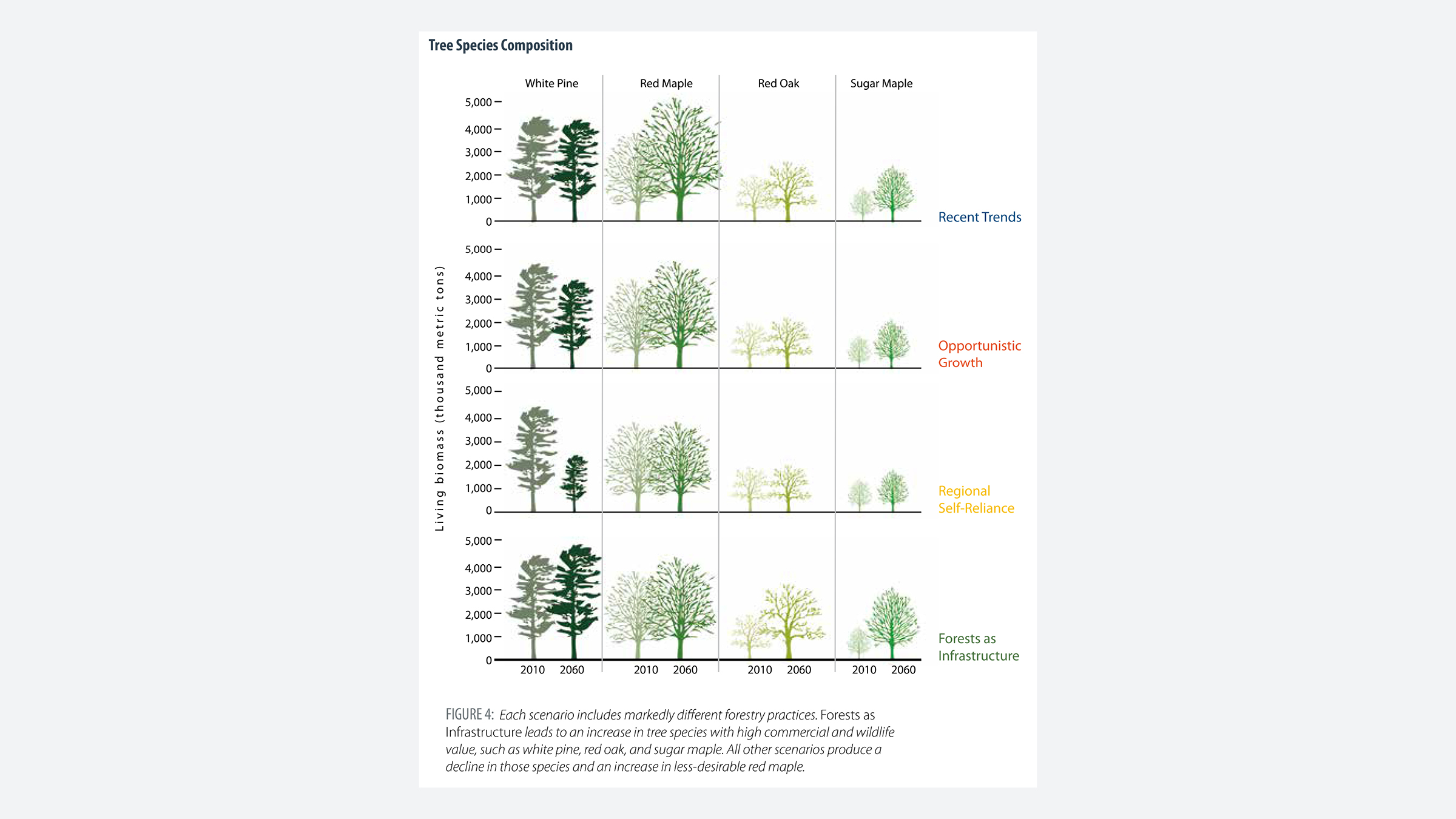

Changes to the Land: Four Scenarios for the Future of the Massachusetts Landscape was published by Harvard Forest in 2014 as a way to build on the previous Wildlands and Woodlands study. Changes to the Land offers four different scenarios for future land-use trajectories in Massachusetts. The document uses 50m x 50m aerial imagery classified with 50 land-use codes and four major categories: forest, agriculture, residential development and mixed-used development.

Three towns were chosen to characterize development patterns along an east-west corridor, from suburban North Andover to sprawl frontier Spencer and finally rural Becket.

Changes to the Land projects scenarios for Massachusetts land-use following four distinct models: recent trends; opportunistic growth; regional self-reliance; and a forests-as-infrastructure model. These scenarios include policy measures aimed at protecting the future of Massachusetts forestlands from development. The report also illustrates the benefits of intersecting land conservation planning with sustainable forestry and clustered development around cities.

Building off Changes to the Land, the Harvard Forest is currently collaborating with Kathleen Theoharides, the Massachusetts Secretary of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA), on the MA Decarbonization Roadmap. The roadmap seeks to identify the strategies, policies, and implementation pathways for MA to achieve an 80% reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, including multiple pathways to net-zero emissions (mass.gov, n.d.). Jonathan Thompson of the Harvard Forest serves as a consultant on the project and is working to produce ecological data for the state to make future land use decisions related to both climate change and forestry.

TIDMARSH WILDLIFE SANCTUARY

Cranberries in the Commonwealth

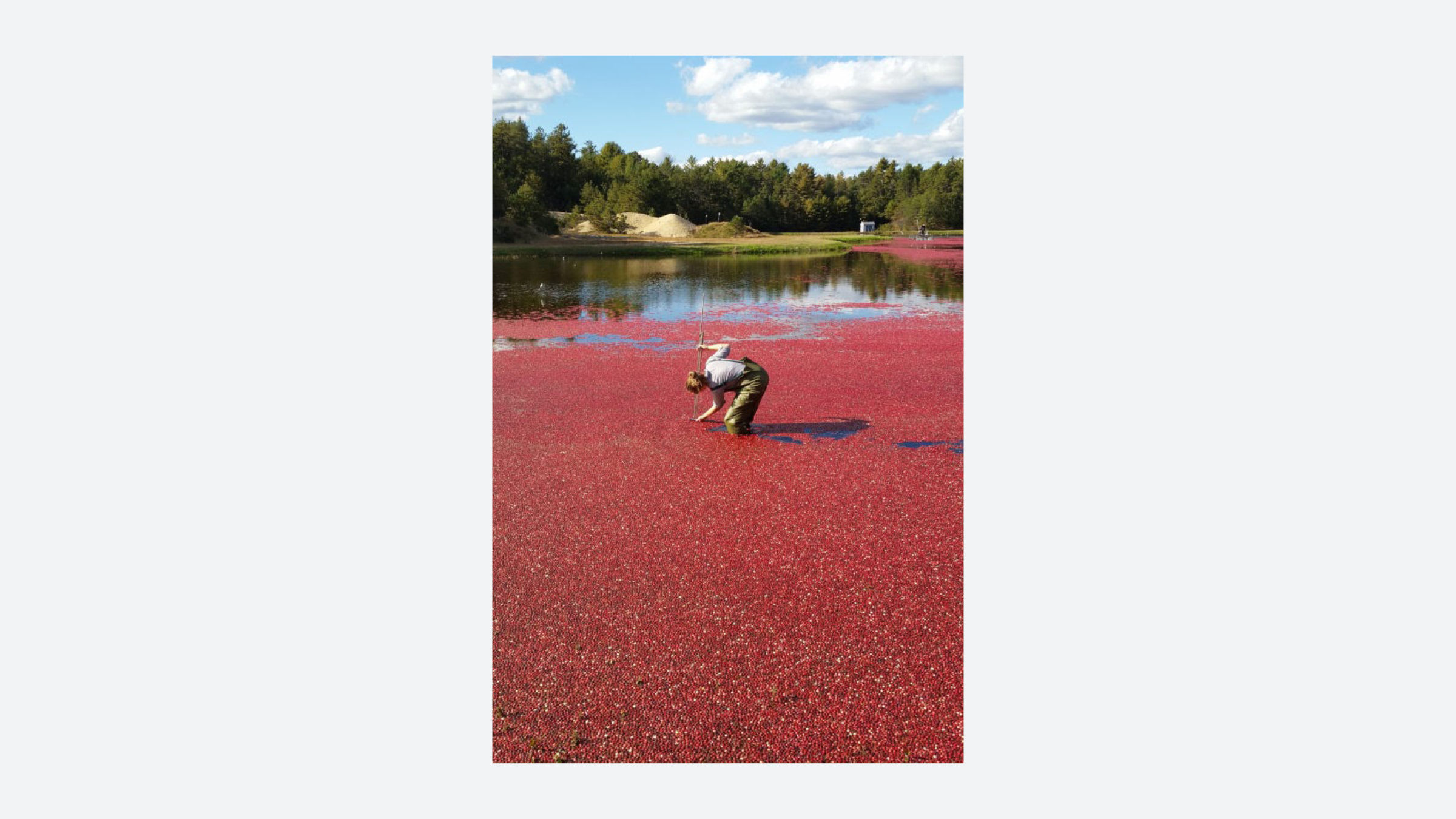

Cranberries - otherwise known as sasumuneash by the 63 Wampanoag tribes who have lived in coastal present-day Massachusetts for 12,000 years - grow spontaneously in Massachusetts wetlands.

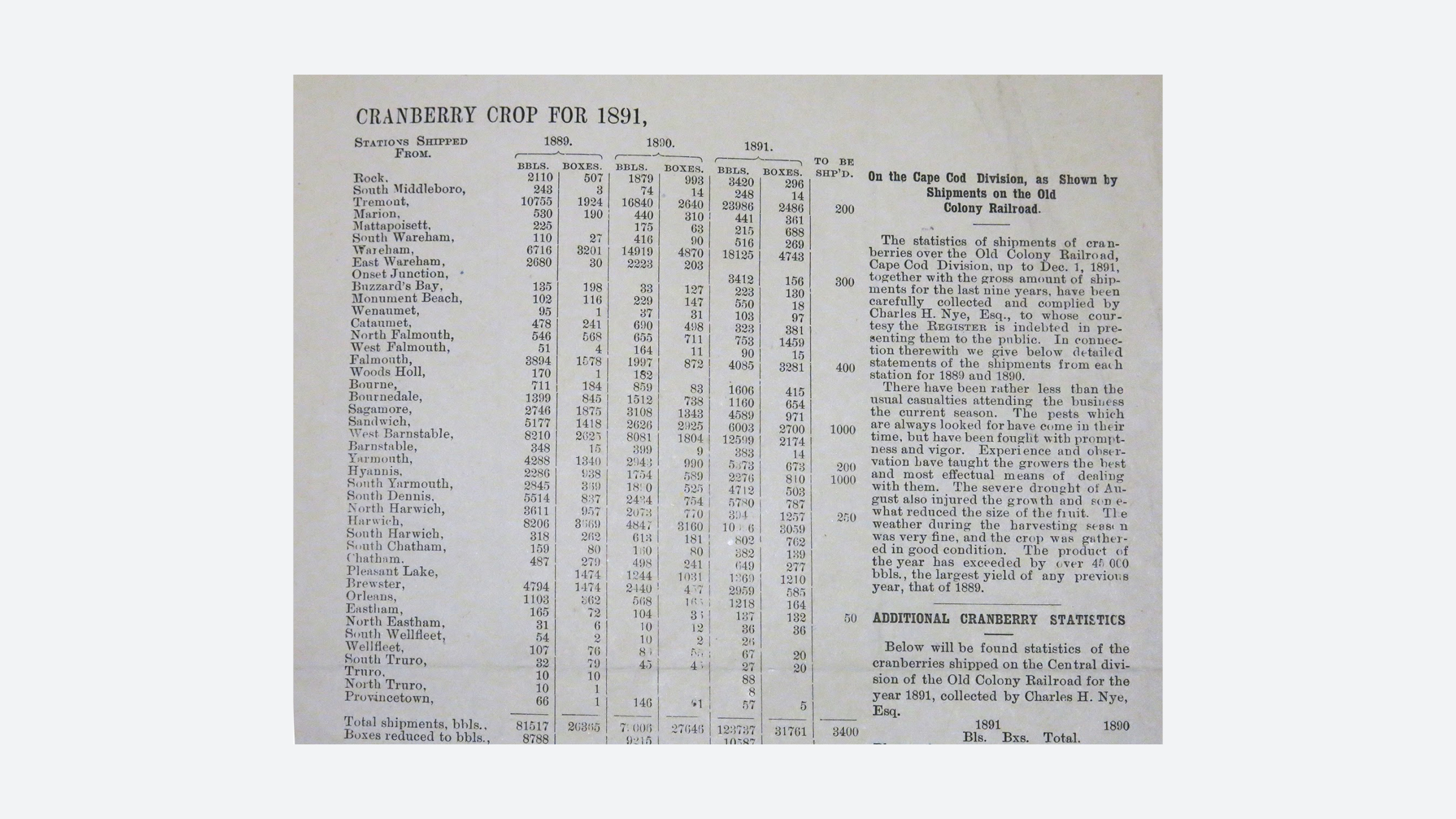

In 1816, Captain Henry Hall noticed that cranberries grew significantly faster when buried beneath a layer of sand. After this discovery, cranberry cultivation became a new agriculture practice that came to fundamentally alter the land cover of southeastern Massachusetts in the 19th century. (Massachusetts Cranberries, 2019). In this early era of cranberry cultivation, low-lying swamplands (home to the wild cranberry) were deforested, drained, covered with a few inches of sand, and then planted with native cranberry. Controlled flooding of the cranberry bogs was a crucial step in this process; water protected the plants from winter winds, removed pests and simplified the harvest process since cranberries floated to the surface. As a result, rivers across the state were dammed to create the ideal conditions for the cranberry harvest.

In the 19th century, the cranberry industry began a process of technological ‘modernization’ and industrial reorganization. Older hand-picking methods were superseded and growers associations and cooperatives such as the Cape Cod Cranberry Growers Association and Ocean Spray Cranberries Inc. emerged. These organizations ushered in the regulated barrel size, a uniform pricing structure, and the advent of marketing campaigns for the fruit itself.

Naturally occuring cranberry bogs provide a range of ecosystem services. They reduce flood risk, increase biodiversity, and uptake carbon. The boom in the industry brought a large-scale reconfiguration of wetland hydrology which drastically hindered such ‘natural’ benefits. Cranberry growers built reservoirs and canals which removed this stream flow from the bogs, preventing water from traveling downstream into ponds or the sea. This dramatic alteration of the existing hydrology manipulated the height of the water table, soil permeability and the carbon content absorbed in the bogs. Soils dried up easily under this system and required extensive irrigation which aimed to mimic the pre-cultivation conditions. Today, the cranberry industry is just a fraction of what it once was in Massachusetts, but degrading practices have had lasting impacts on wetland ecosystems. There is a clear need to reassess this agricultural practice in order to plan for a changing climate where the state can harness the potential of wetland ecosystems as climate adaptive infrastructure.

In 2016, the Cranberry Bog Revitalization Task Force was created to assess future options for the industry in Massachusetts. One recommendation was to develop exit strategies for interested landowners to convert their farms into wetlands. Tidmarsh Farms, a former cranberry farm in Plymouth Massachusetts set a precedent in 2008 when it converted its bogs into “the largest freshwater restoration ever completed in the Northeast” according to the Mass Audubon Society (Living Observatory, 2019).

Tidmarsh Wildlife Sanctuary

In 1989, Evan Schulman and Glorianna Davenport purchased Tidmarsh Farms, a 600 acre property in Plymouth, Massachusetts . At that time the farm produced 1% of Ocean Spray’s annual harvest. In the early 2000s, the family decided to cease farming operations and in 2008 began a process of land reclamation and restoration, converting the bogs into wetlands—a project that involved removing seven earth dams, restoring river flow, adding over 3,000 logs to the stream channel, and replanting the wetlands.

Tidmarsh Farms covers 17.8% of the Beaver Dam Brook coastal watershed; the water that flows through the farm’s river eventually empties in the Atlantic Ocean. Thus, the health of Tidmarsh’s wetlands impacts the ecological health of the entire South Coastal watershed and coastal zone/region.

To restore the wetlands, Schulman and Davenport partnered with the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NCRS) Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP), and the Massachusetts Department of Fish and Game’s Division of Ecological Restoration. The East Tidmarsh Farms Restoration project lasted from 2011 to 2016 and cost an estimated $13,600 per acre, for a total approximate cost of $3 million. Additional funding came from the sale of the property to the The Massachusetts Audubon Society in 2017. The project’s budget provides a baseline - or reference point - for other cranberry farmers considering similar reclamation endeavors/initiatives.

During the restoration work, Glorianna Davenport, a visiting professor at the MIT Media Lab, established the Living Observatory, a 501(c) non-profit organization to invite scientists, artists and engineers to document the revitalization process and the transitions over time.

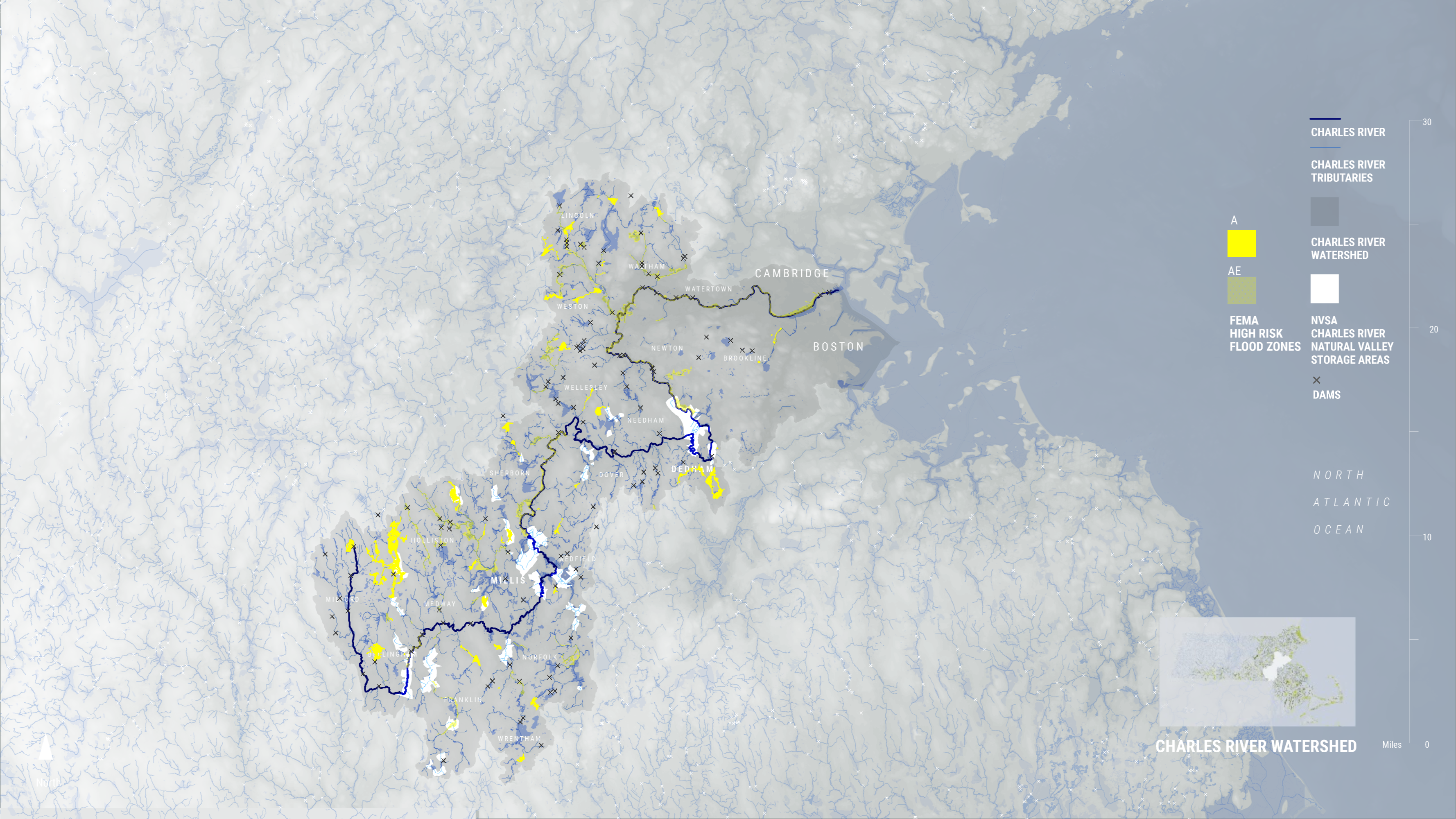

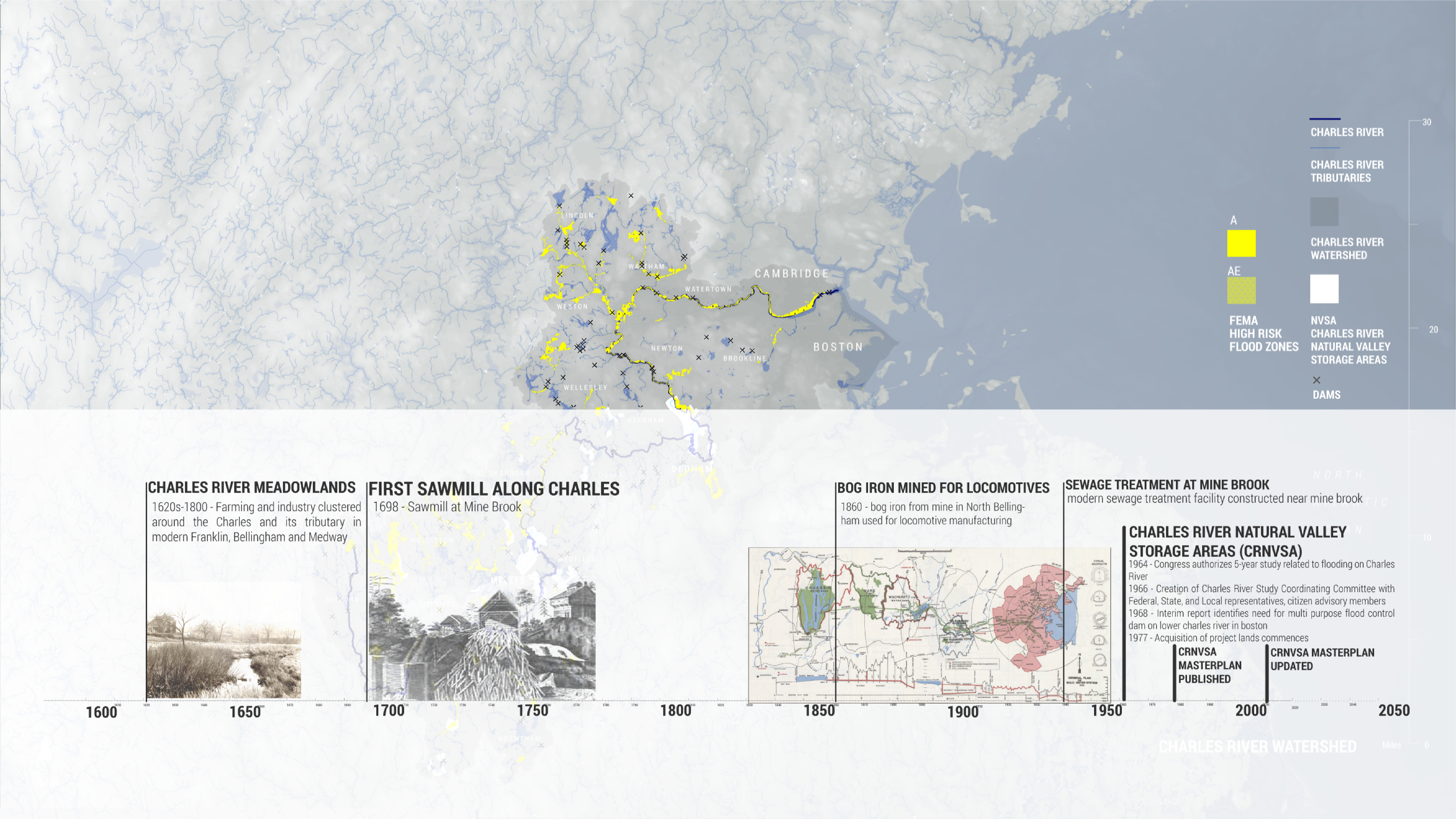

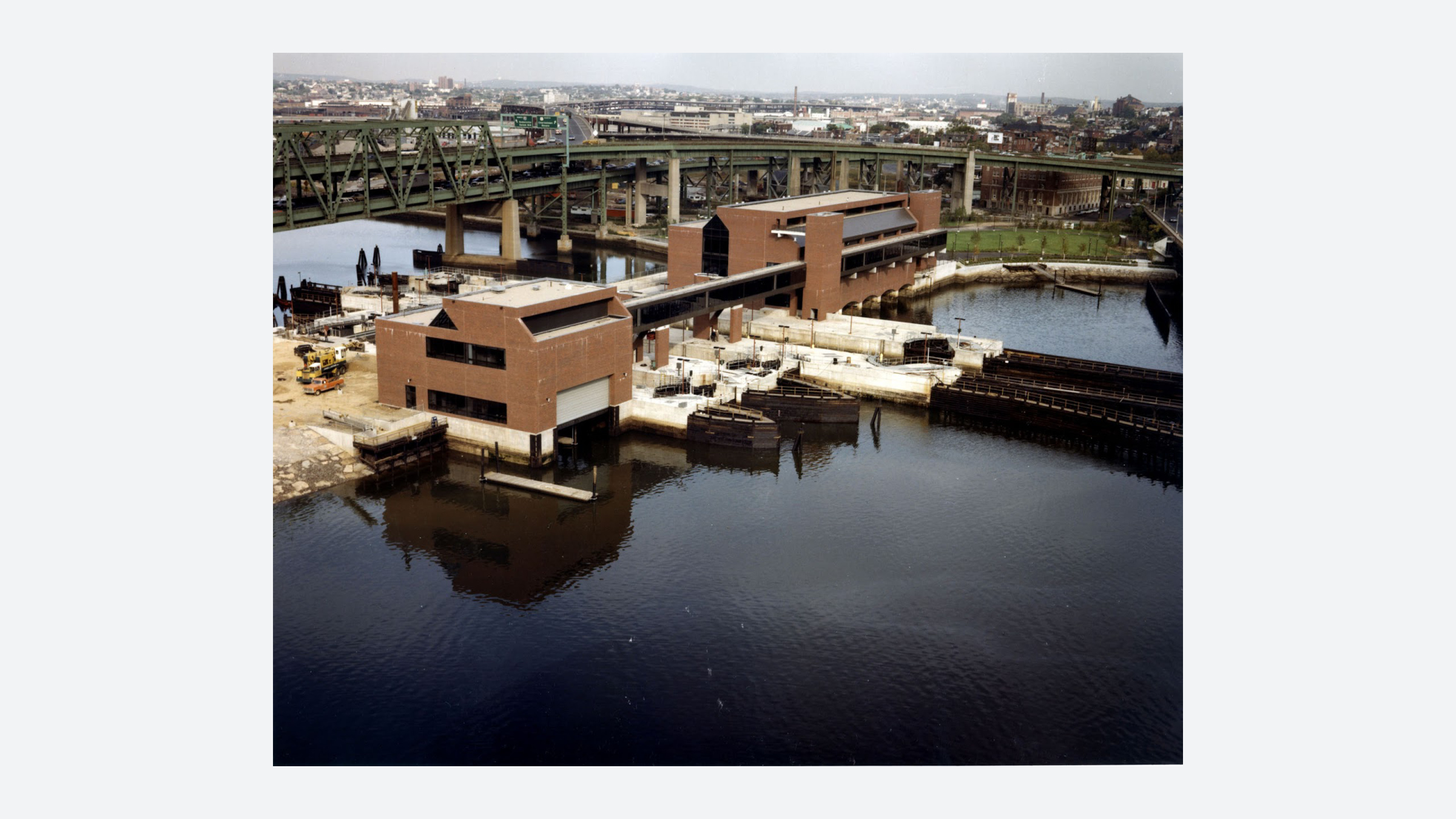

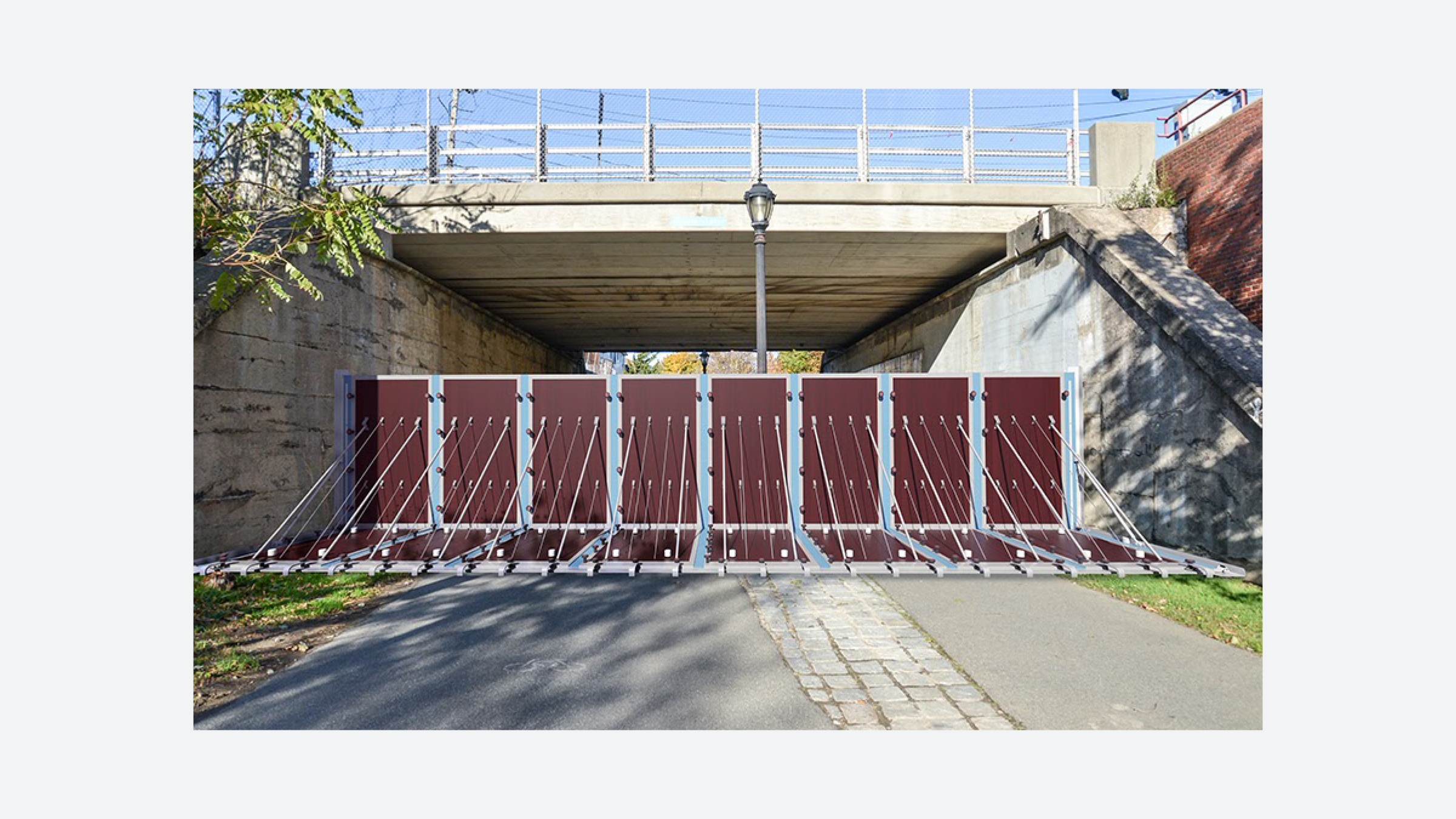

CHARLES RIVER FLOOD CONTROL

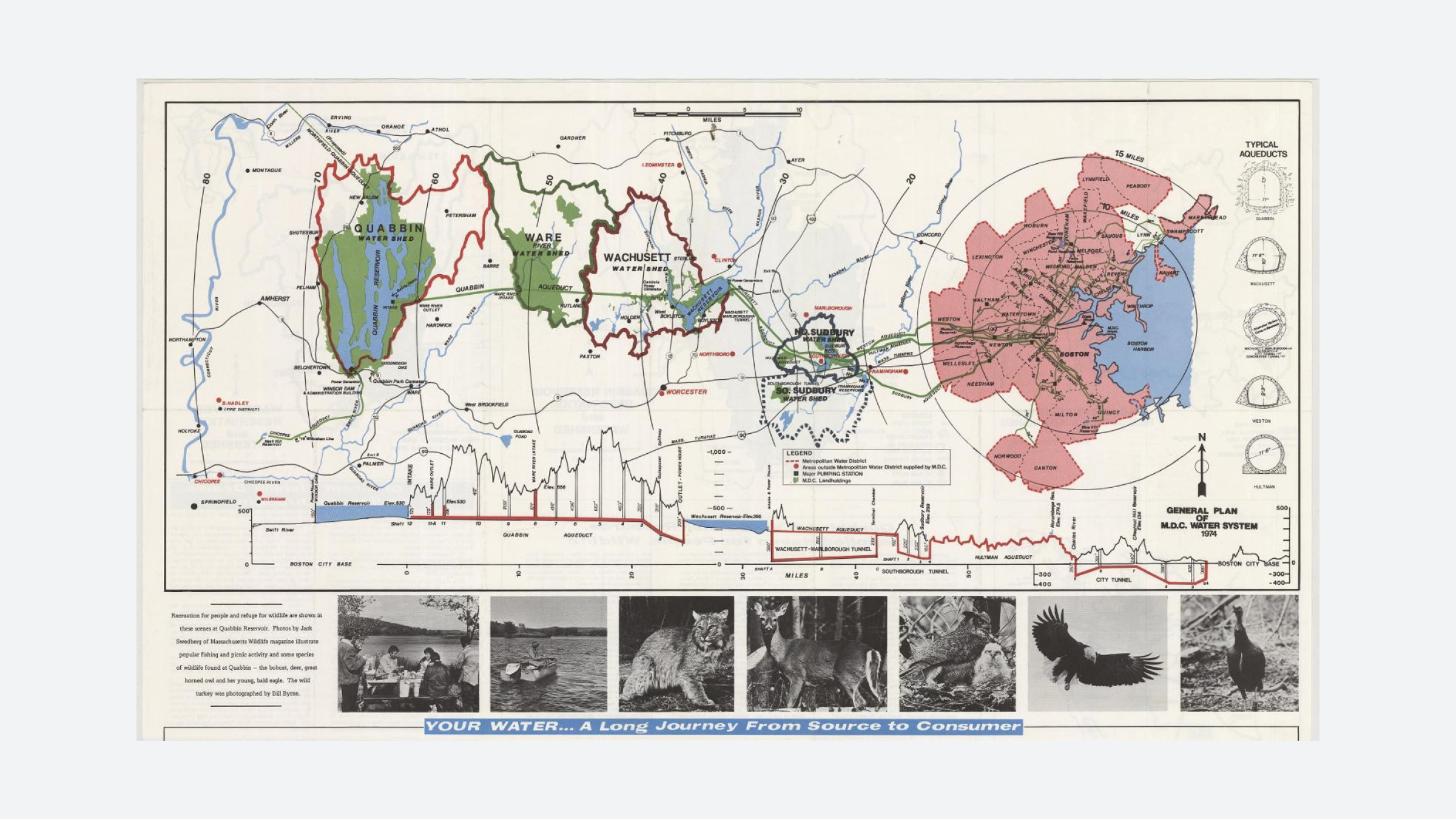

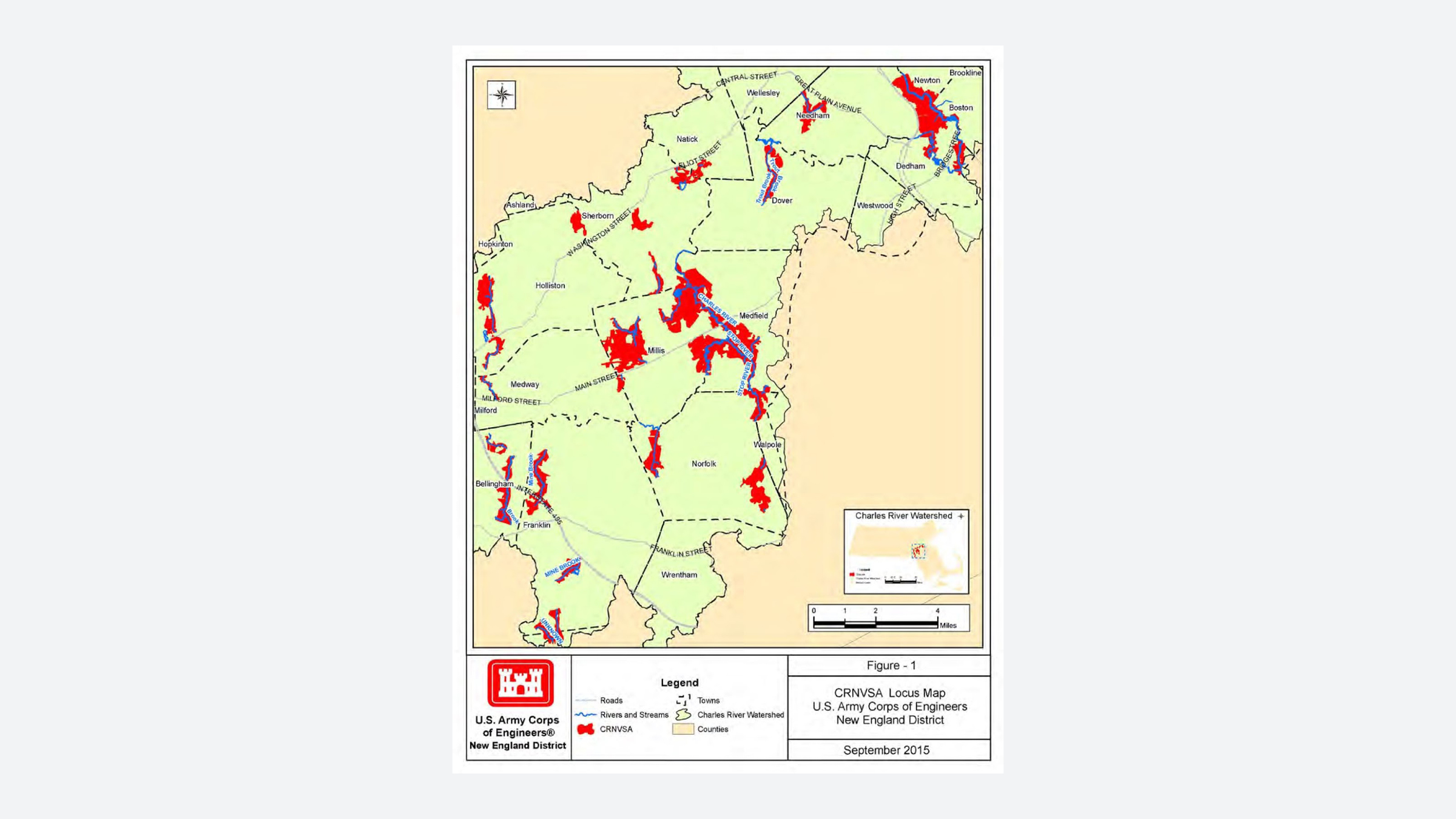

The 80 mile long Charles River, and its tightly managed watershed have long been the subject of concerted human intervention. Dams, barriers, and riverfront parks have all been constructed along the river in an effort to ameliorate flood risk. In the 1970s the United State Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) New England Division took on a watershed-scale approach to flood control, through the Charles River Natural Valley Storage Area (CRNVA), after a multi-year study in response to severe flood events in the 1950’s. After much pushback from the local advocacy organization, the Charles River Watershed Association, the Army Corps decided to break with the tradition of damming the river and opted to utilize non-structural interventions such as wetlands for water storage.

The project used large-scale land acquisition to create a system of natural reservoirs in order to prevent flooding downstream in high risk areas. The Army Corps designated these land acquisitions, “Natural Valley Storage” areas— their term for wetlands. The USACE purchased the first storage area in May 1977 and continued to acquire land until September 1983. In total, 307 square miles of land was acquired at a total cost of over $8.3 million. Lands acquired under the CRNVA project were often existing wetlands or open space under intense development pressure. Today, many of these reserves are open to the public for fishing and recreation.

While these natural reservoirs continue to act as critical flood mitigation infrastructure, questions remain around the model itself. Critics of this model question the need for intervention by a federal agency rather than local government as well as the efficiency of using federal dollars to purchase land rather than push for land use regulation at a local level. Over the course of this project, the USACE undertook several studies of other Massachusetts watersheds in anticipation of replicating this strategy; none were found to be financially practical.

The project used large-scale land acquisition to create a system of natural reservoirs in order to prevent flooding downstream in high risk areas. The Army Corps designated these land acquisitions, “Natural Valley Storage” areas— their term for wetlands. The USACE purchased the first storage area in May 1977 and continued to acquire land until September 1983. In total, 307 square miles of land was acquired at a total cost of over $8.3 million. Lands acquired under the CRNVA project were often existing wetlands or open space under intense development pressure. Today, many of these reserves are open to the public for fishing and recreation.

While these natural reservoirs continue to act as critical flood mitigation infrastructure, questions remain around the model itself. Critics of this model question the need for intervention by a federal agency rather than local government as well as the efficiency of using federal dollars to purchase land rather than push for land use regulation at a local level. Over the course of this project, the USACE undertook several studies of other Massachusetts watersheds in anticipation of replicating this strategy; none were found to be financially practical.

CLIMATE READY BOSTON

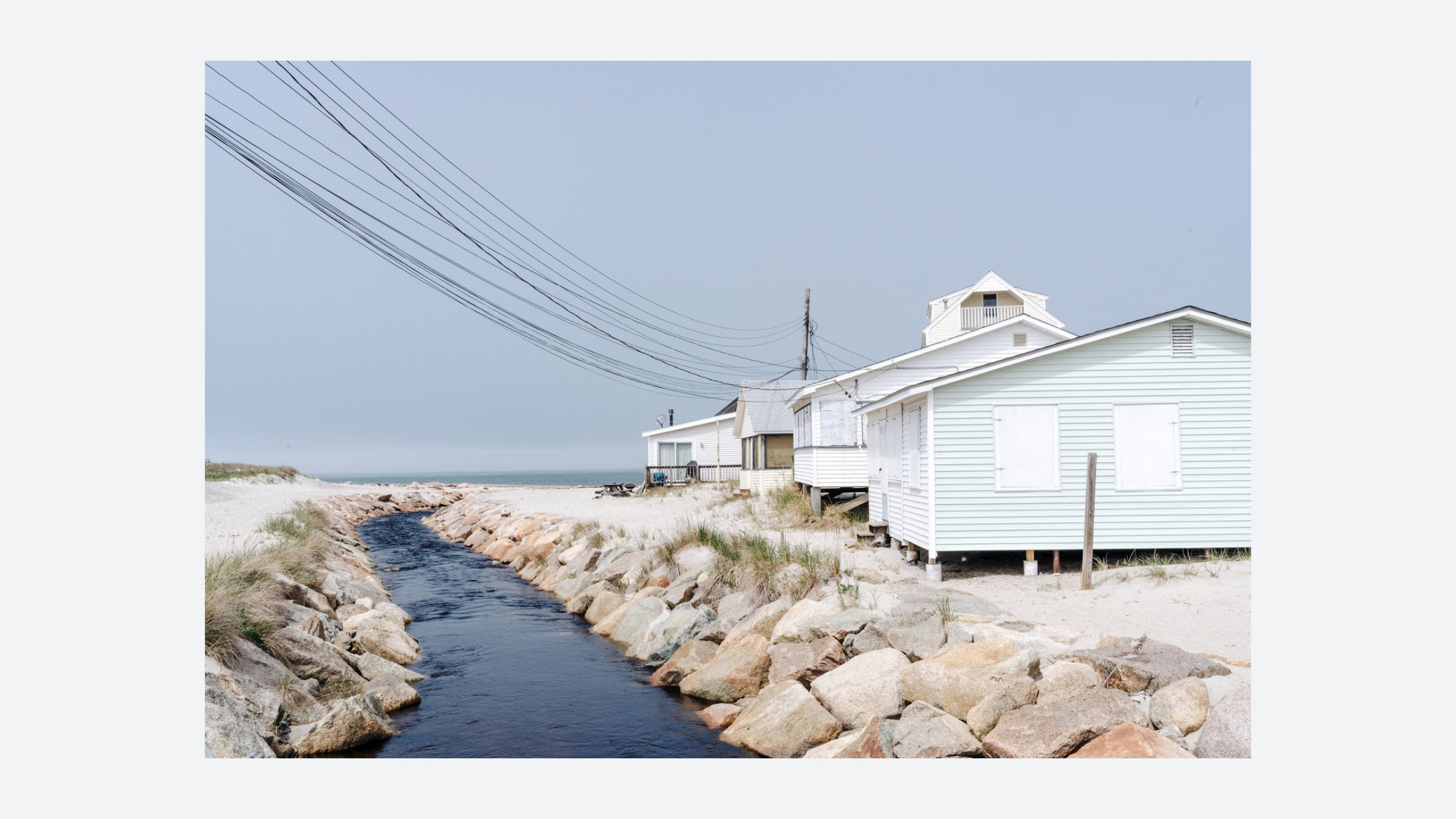

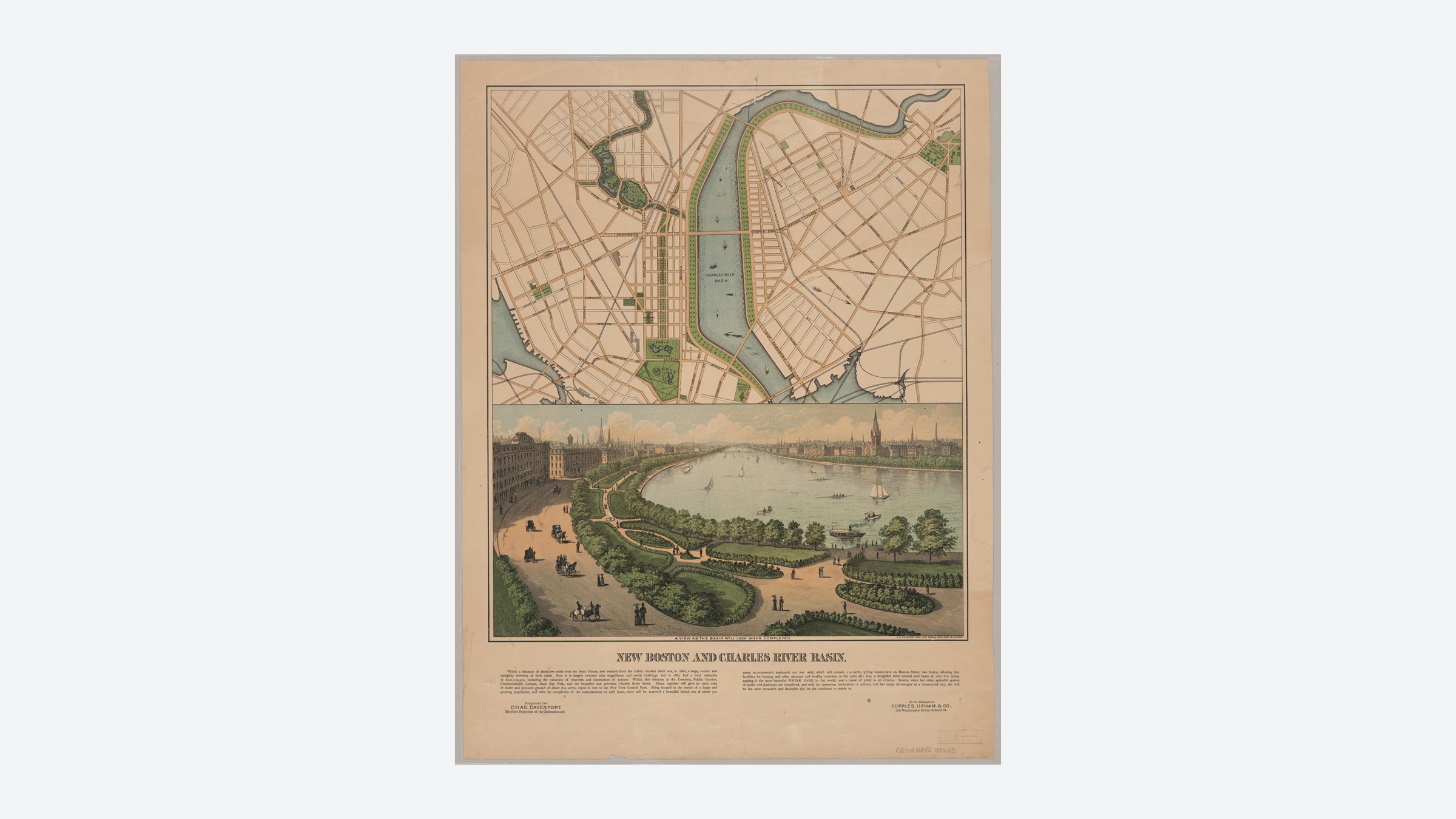

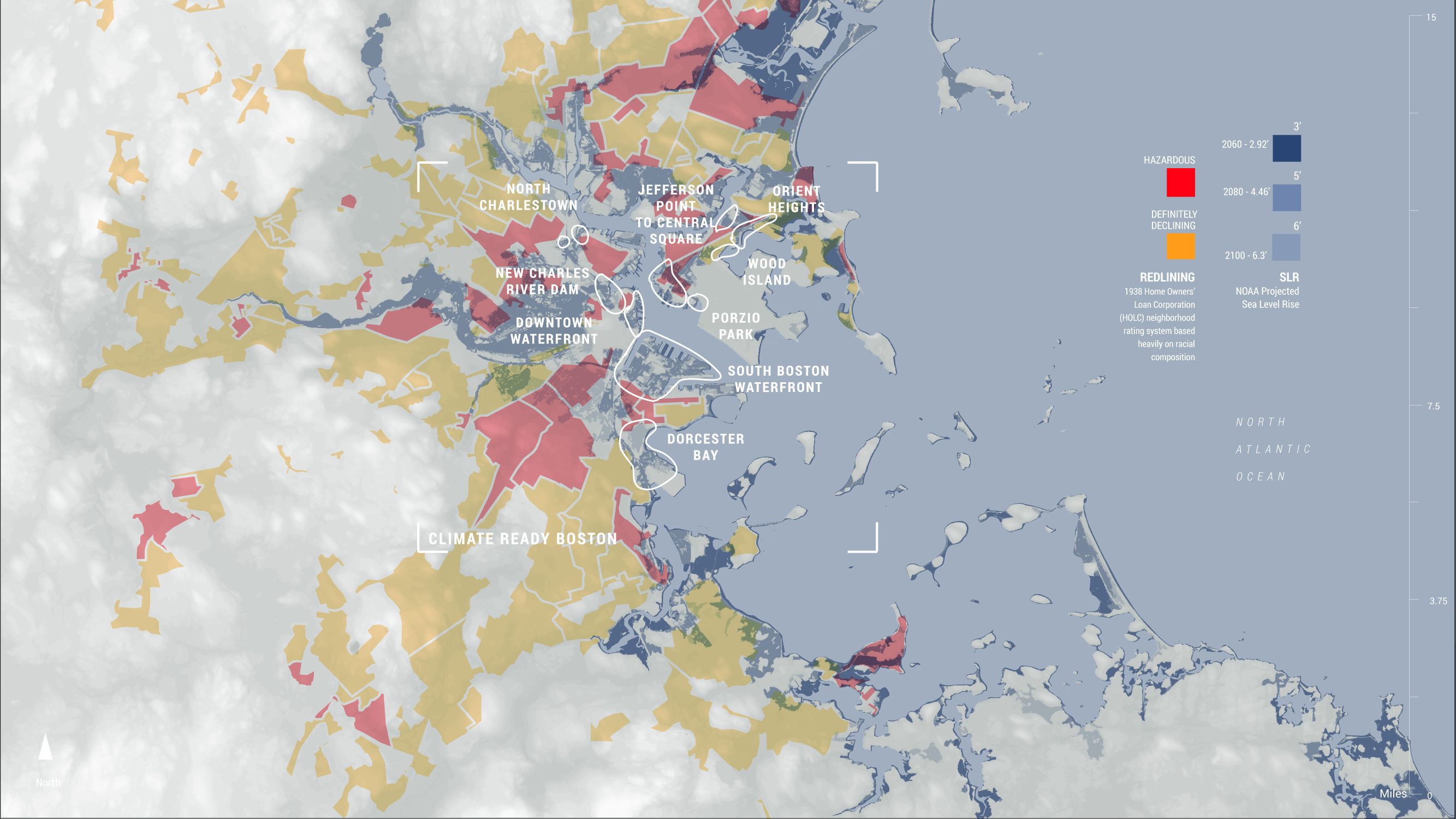

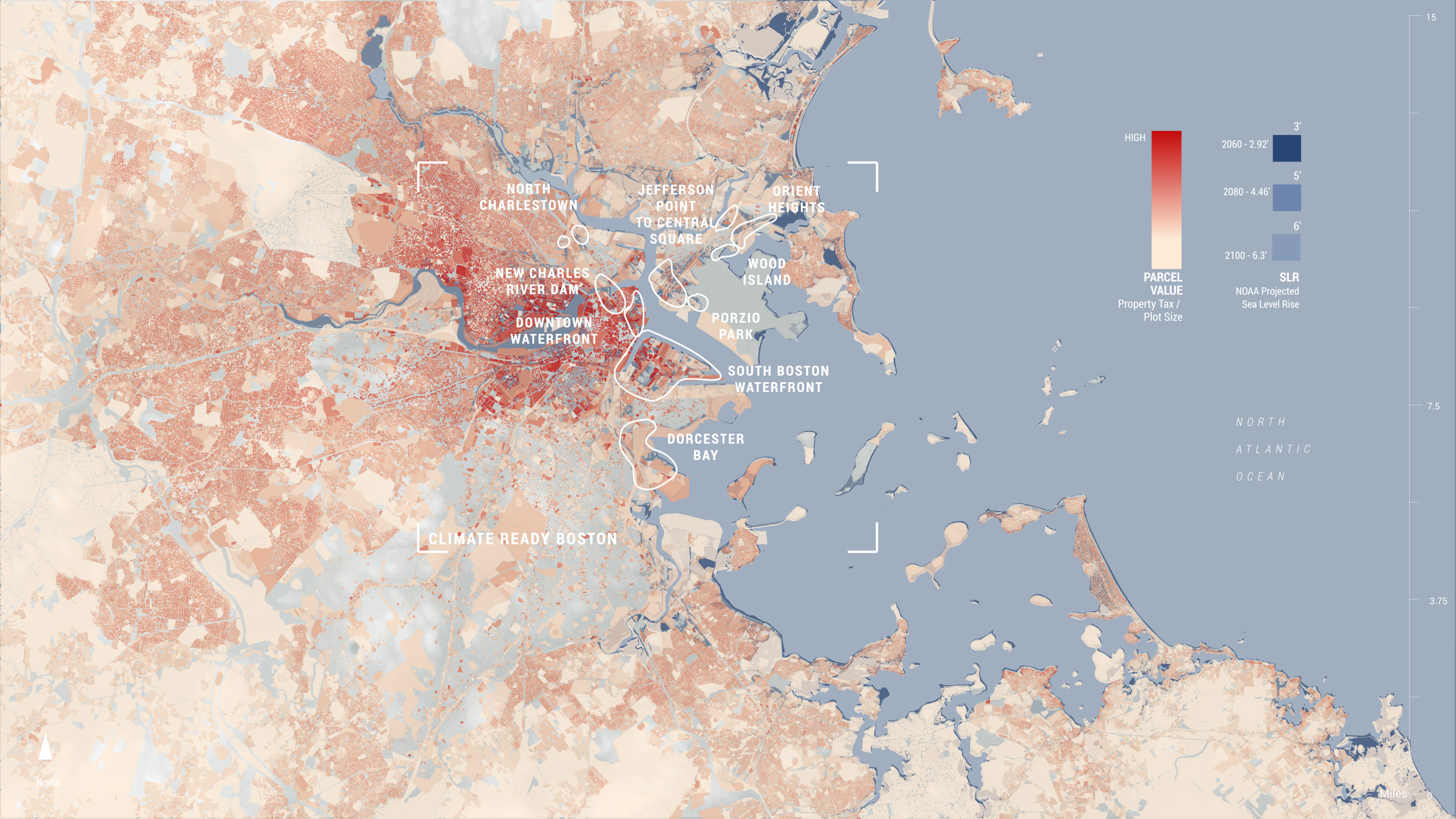

Climate Ready Boston is the city of Boston's plan to prepare for coastal flooding that is predicted to become more frequent due to global warming. Since the 19th century, Boston has expanded its surface area nearly threefold through land infill projects, many of which are ongoing, and most of which are directly threatened by storm surges related to rising seas levels.

In the 1930’s, a federal land appraisal system created color coded ‘lending risk’ maps; neighborhoods inhabited by marginalized communities were coded red for “hazardous” or yellow for “definitely declining.” Since insurers and lenders came to rely on these maps, discriminated communities quickly saw major and lasting disinvestment. Today we know this practice as “redlining.” The effects of these maps are still felt as redlined neighborhoods often have fewer resources with which to deal with their heightened vulnerability to climate and environmental risk. Both the process of infilling and redlining have had a huge impact on where climate infrastructure is needed and who is still at risk in the wake of this planning.

In 2016, Boston hired its first Chief Resilience Officer, Dr. Atyia Martin, under a two-year grant from 100 Resilient Cities (a program initiated by The Rockefeller Foundation). Dr. Martin’s city-wide resilience strategy was the first in the 100 Resilient Cities’ network to center on racial equity, social justice, and social cohesion.During her tenure, she published Resilient Boston, a comprehensive plan and roadmap for envisioning resilience in Boston through the lens of race and equity. Climate Ready Boston is just one of ten projects that came out of this report.

In the 1930’s, a federal land appraisal system created color coded ‘lending risk’ maps; neighborhoods inhabited by marginalized communities were coded red for “hazardous” or yellow for “definitely declining.” Since insurers and lenders came to rely on these maps, discriminated communities quickly saw major and lasting disinvestment. Today we know this practice as “redlining.” The effects of these maps are still felt as redlined neighborhoods often have fewer resources with which to deal with their heightened vulnerability to climate and environmental risk. Both the process of infilling and redlining have had a huge impact on where climate infrastructure is needed and who is still at risk in the wake of this planning.

In 2016, Boston hired its first Chief Resilience Officer, Dr. Atyia Martin, under a two-year grant from 100 Resilient Cities (a program initiated by The Rockefeller Foundation). Dr. Martin’s city-wide resilience strategy was the first in the 100 Resilient Cities’ network to center on racial equity, social justice, and social cohesion.During her tenure, she published Resilient Boston, a comprehensive plan and roadmap for envisioning resilience in Boston through the lens of race and equity. Climate Ready Boston is just one of ten projects that came out of this report.

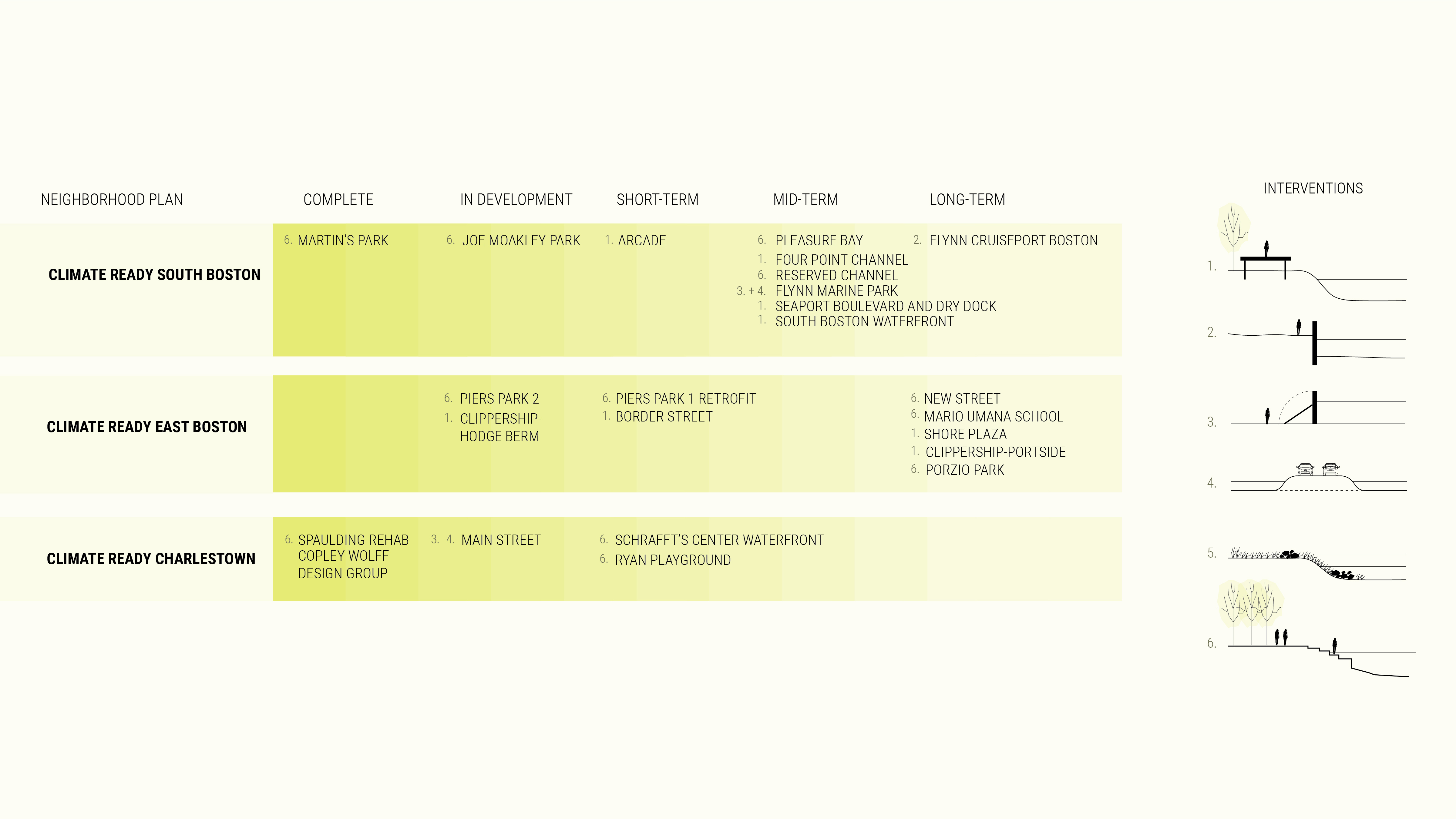

Climate Ready Boston is a metro-Boston plan to build infrastructure that accounts for more extreme heat, rain, and flooding caused by climate change/global warming. The plan consists of proposals and projects across various Boston neighborhoods; each initiative functioning as an isolated project, responsible for its own community participation processes and for securing and managing its own funding.

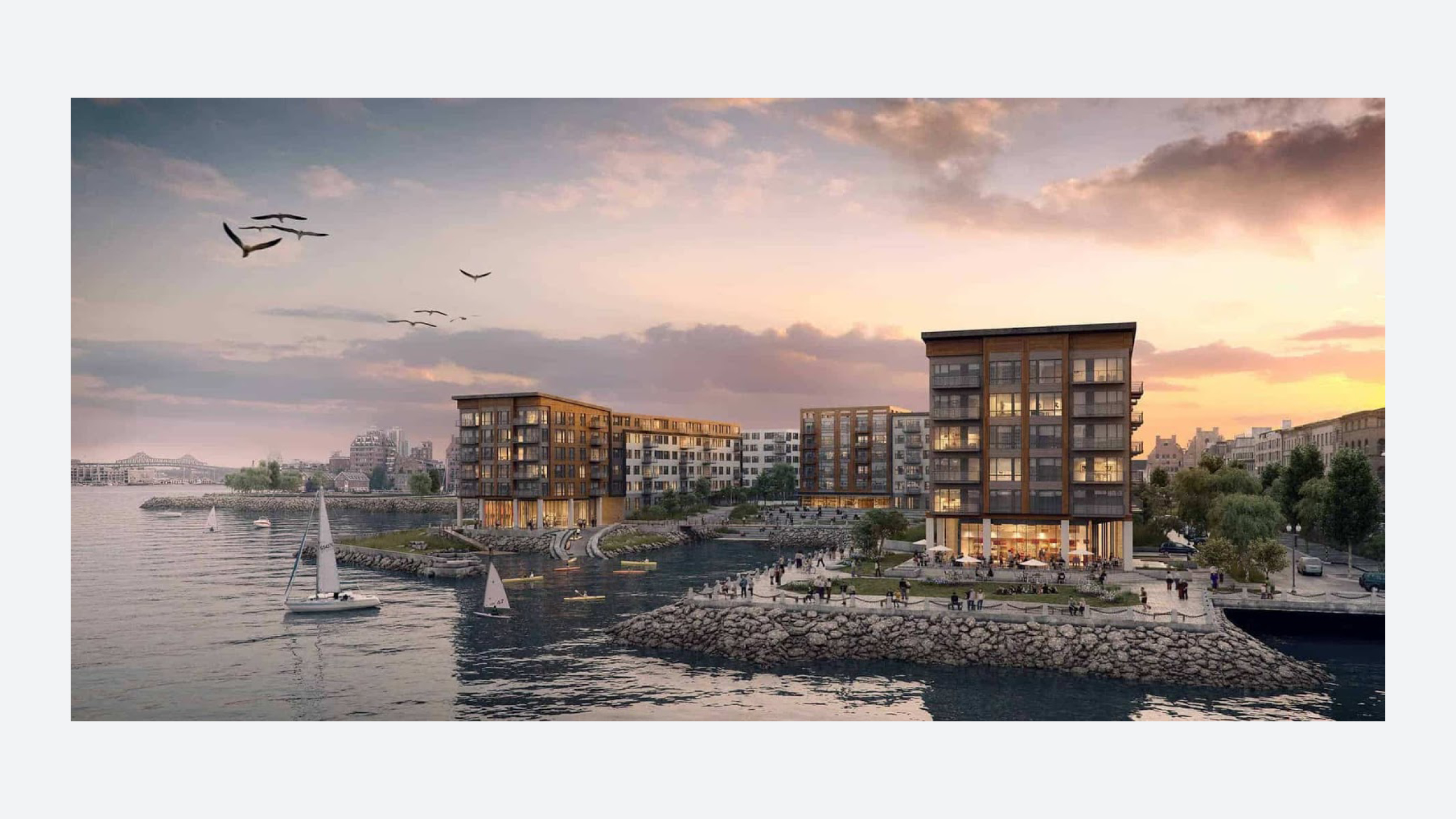

Despite the city's intentions to protect its residents, concerns persist over whether the resources needed to complete the projects outlined will be equitably distributed to Boston's most vulnerable communities. Additionally, concerns over “climate gentrification” pervade. For instance, in East Boston, an elevated waterfront park built to protect the neighborhood from storm surges and provide open space is surrounded and funded by luxury waterfront developments. Questions remain as to whether residents living in older buildings behind the new luxury developments are in fact adequately protected by the elevated waterfront park and whether they feel these open space amenities are a part of their neighborhood at all.

Climate Ready Boston is a comprehensive, though complex and at times conflicted, attempt to address the risks faced by metro-Boston citizens in the age of climate change. On the one hand, the city emphasizes (and funds) climate change specific infrastructure initiatives and delegates considerable power to local communities. On the other hand, shiny impressive looking projects often cover up more deeply entrenched inequities, as some citizens benefit from new parks and recreation areas, while others are excluded or pushed to the periphery of risk-mitigation plans. While Climate Ready Boston has been a career boon for practicing architects and landscape architects, as a number of firms have been consulted or contracted to design alternatives to building hard and brittle coastal barriers, many of these projects remain complicit in cycles of development and displacement.

Despite the city's intentions to protect its residents, concerns persist over whether the resources needed to complete the projects outlined will be equitably distributed to Boston's most vulnerable communities. Additionally, concerns over “climate gentrification” pervade. For instance, in East Boston, an elevated waterfront park built to protect the neighborhood from storm surges and provide open space is surrounded and funded by luxury waterfront developments. Questions remain as to whether residents living in older buildings behind the new luxury developments are in fact adequately protected by the elevated waterfront park and whether they feel these open space amenities are a part of their neighborhood at all.

Climate Ready Boston is a comprehensive, though complex and at times conflicted, attempt to address the risks faced by metro-Boston citizens in the age of climate change. On the one hand, the city emphasizes (and funds) climate change specific infrastructure initiatives and delegates considerable power to local communities. On the other hand, shiny impressive looking projects often cover up more deeply entrenched inequities, as some citizens benefit from new parks and recreation areas, while others are excluded or pushed to the periphery of risk-mitigation plans. While Climate Ready Boston has been a career boon for practicing architects and landscape architects, as a number of firms have been consulted or contracted to design alternatives to building hard and brittle coastal barriers, many of these projects remain complicit in cycles of development and displacement.

While Climate Ready Boston represents a step toward preemptive climate change planning, its plans fail to address existing pressures at play across the city. Concerns about limited affordable housing, insufficient public health services, and increasing displacement of certain low-income and at-risk communities are justifiably causing residents to ask whether or not projects like flood resilient waterfront parks are not in fact perpetuating existing inequities. Similarly, Climate Ready Boston exposes tensions between large-scale planning aims and implementation strategies that rely on the atomized and localized funding of projects. Because individual projects have their own leadership, funding strategies, and community outreach commitments, Climate Ready Boston as a whole may struggle to create a coherent, collective set of results.

CONCLUSIONS

Massachusetts is fortunate to have the funding and political motivation to plan for statewide disruptions caused by the climate crisis. Among other initiatives, Massachusetts can build climate specific infrastructure, restore wetlands, and experiment with new forestry models in a designated research forest. However, these initiatives are unlikely to be implemented in an equitable way, at least if legacies of structural inequality influence current and future planning. And while many initiatives -- such as the Charles River Flood Control Program -- focus on urban areas in order to protect residential and commercial property values, marginalized communities remain among the last to see tangible benefits from climate-forward design and planning, and often lack the resources to determine their own solutions.

While these four cases are not all encompassing, they are previews of a larger toolkit of design approaches highlighted in the coming weeks. The themes that arise in these cases; fractured funding mechanisms, indigenous erasure, embedded injustices, local versus federal power, among others will pervade many of the upcoming cases.

While these four cases are not all encompassing, they are previews of a larger toolkit of design approaches highlighted in the coming weeks. The themes that arise in these cases; fractured funding mechanisms, indigenous erasure, embedded injustices, local versus federal power, among others will pervade many of the upcoming cases.

Below are a series of prompting questions:

- How are adaptive capacities to climate change distributed across Massachusetts?

- What are counter-models to the “green climate gentrification” cycle?

- What are the limits to a “resilient” plan for Massachusetts? Who are these designs/plans ‘protecting’?

- Where do mitigation and adaptation efforts conflict? Where do they complement each other?

- Which new forms of boundaries and delineations do these projects create? Which do they dissolve or modify?

SOURCES

Buzzards Bay Coalition. “New research is unlocking the nitrogen secrets hidden in different types of cranberry bogs.” December 4, 2018. https://www.savebuzzardsbay.org/news/new-research-nitrogen-secrets-different-types-of-cranberry-bogs/

Harvard Forest. “History.” 2020. https://harvardforest.fas.harvard.edu/history/

Kousky, Carolyn. "The Economics and Politics of 'Green' Flood Control: A Historical Examination of Natural Valley Storage Protection by the Corps of Engineers." Resources for the Future Discussion Paper 14-07 (2014).

“MA Decarbonization Roadmap.” Mass.gov, n.d. https://www.mass.gov/info-details/ma-decarbonization-roadmap.

Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe. “Timeline.” 2020. https://mashpeewampanoagtribe-nsn.gov/timeline

Massachusetts Cranberries. “History.” 2019. https://www.cranberries.org/history

Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management. “The Worst Massachusetts Hurricanes of the 20th Century.” 2020.

"Restoration Sites." Living Observatory. Accessed September 14, 2020. http://www.livingobservatory.org/restoration-sites.

Thompson, Jonathan, Kathy Fallon Lambert, David Foster, Meghan Blumstein, Eben Broadbent, Angelica Almeyda Zambrano. Changes to the Land: Four Scenarios of the Massachusetts Landscape. Petersham: Harvard Forest, 2014.