CONNECTED CITY

Overview

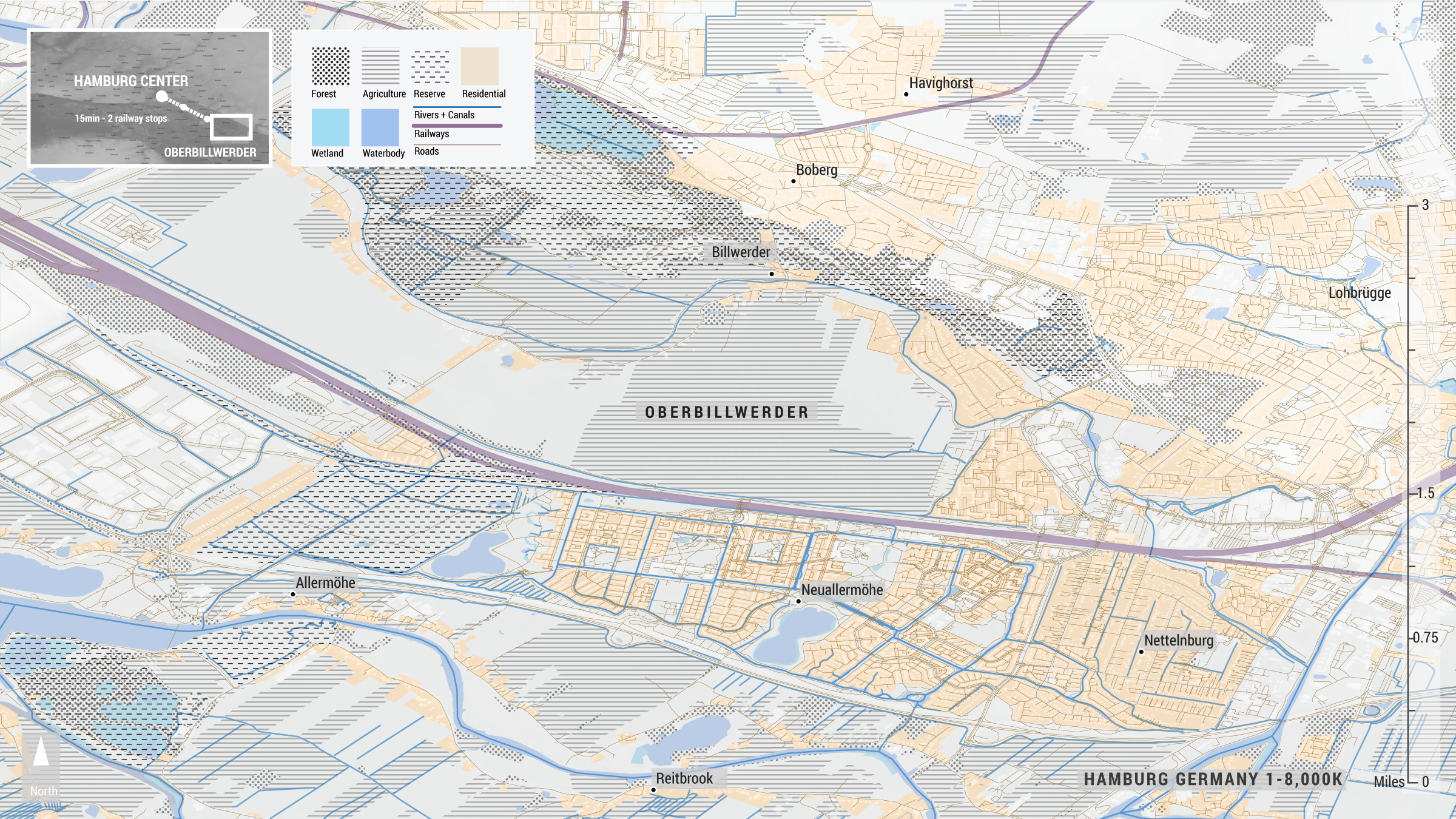

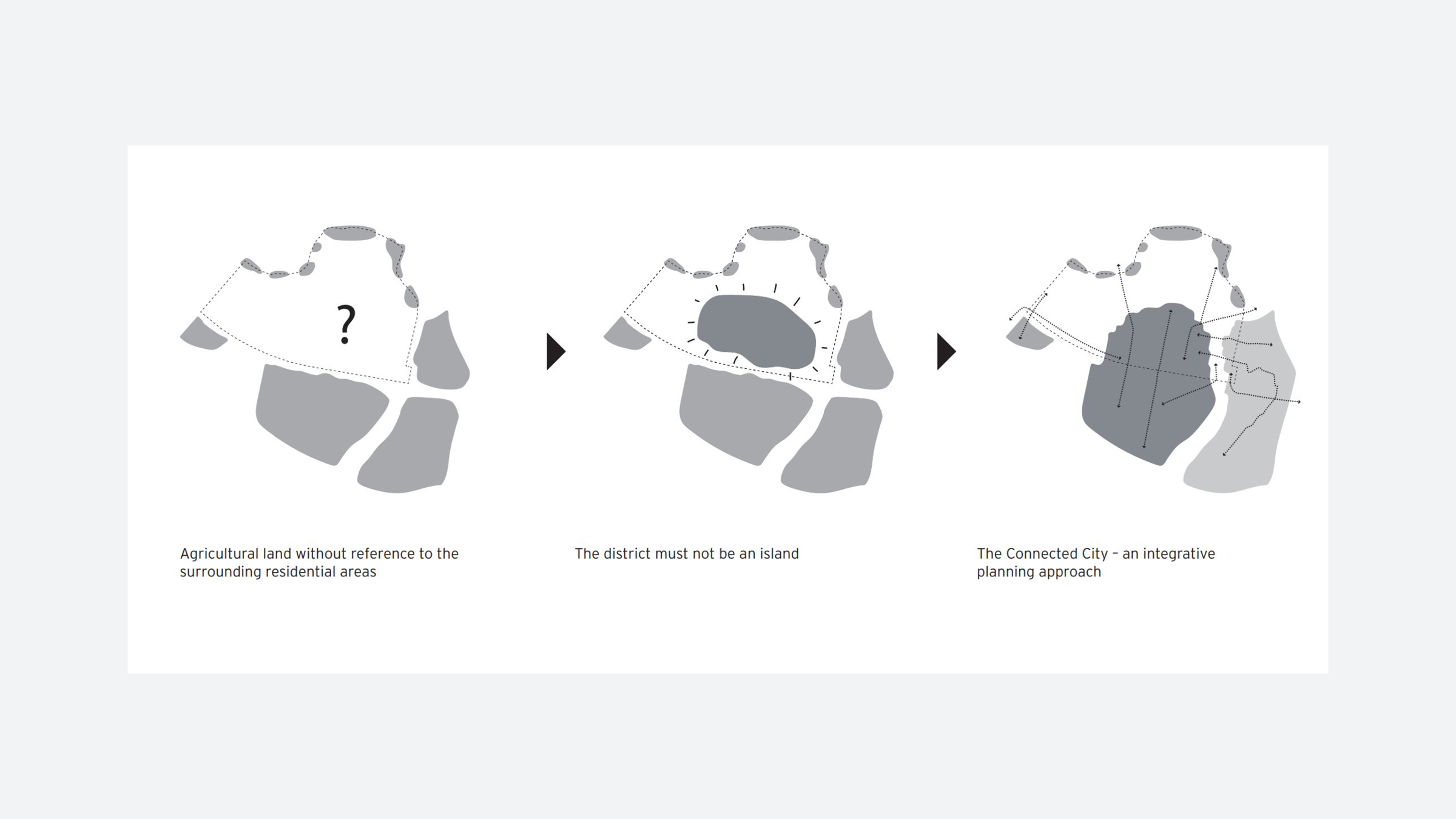

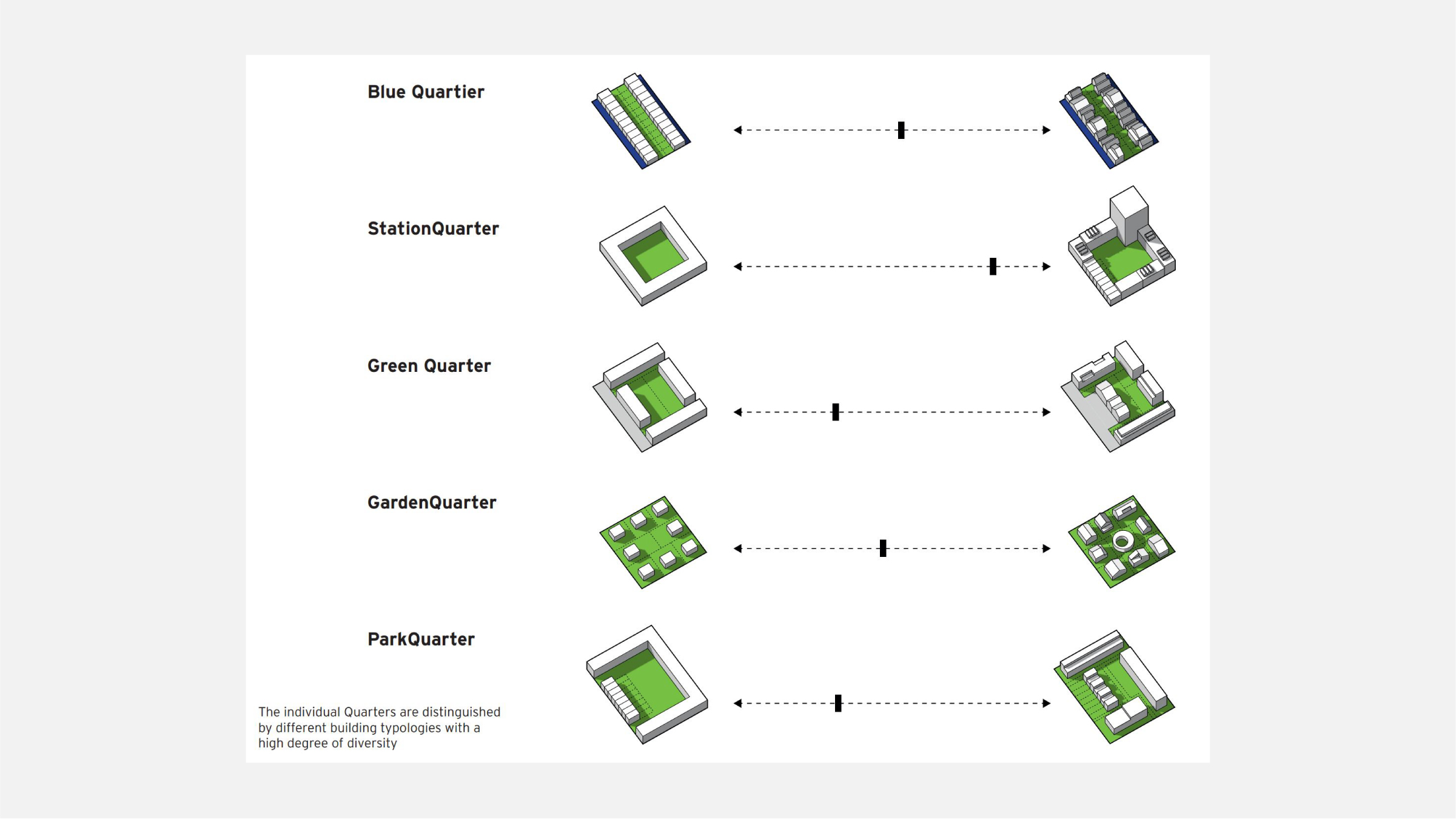

The Connected City is a 124-hectare masterplan for the development of a new neighborhood and administrative district at the southeastern edge of Hamburg, Germany. The new district, Oberbillwerder, follows the city's recent plans for developing climate-forward, low-carbon, walkable, mixed-use urban neighborhoods. The plan’s title – The Connected City – derives from Hamburg’s aim to link Hamburg’s suburban communities and agricultural landscape to its historic city center on the Elbe river. The Oberbillwerder project emerged from a competition organized by IBA Hamburg, a subsidiary of the municipal government that manages several new development projects initiated by the city. The winning plan, proposed by the team of ADEPT, Karres en Brands, and Transsolar, analyzed the transformation of the Hamburg landscape from a marshland to a mosaic of urban clusters surrounded by suburbs and agricultural fields.

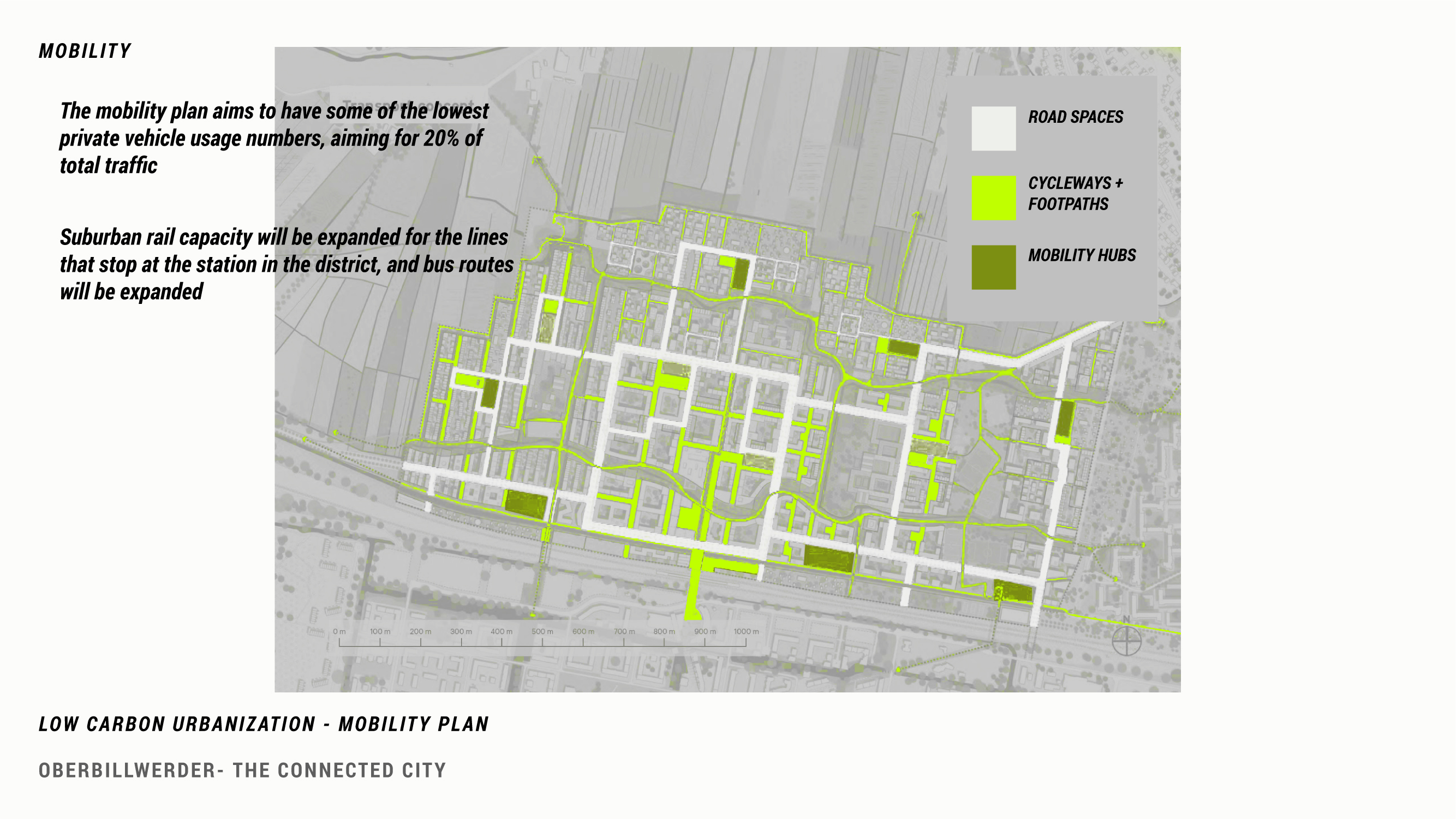

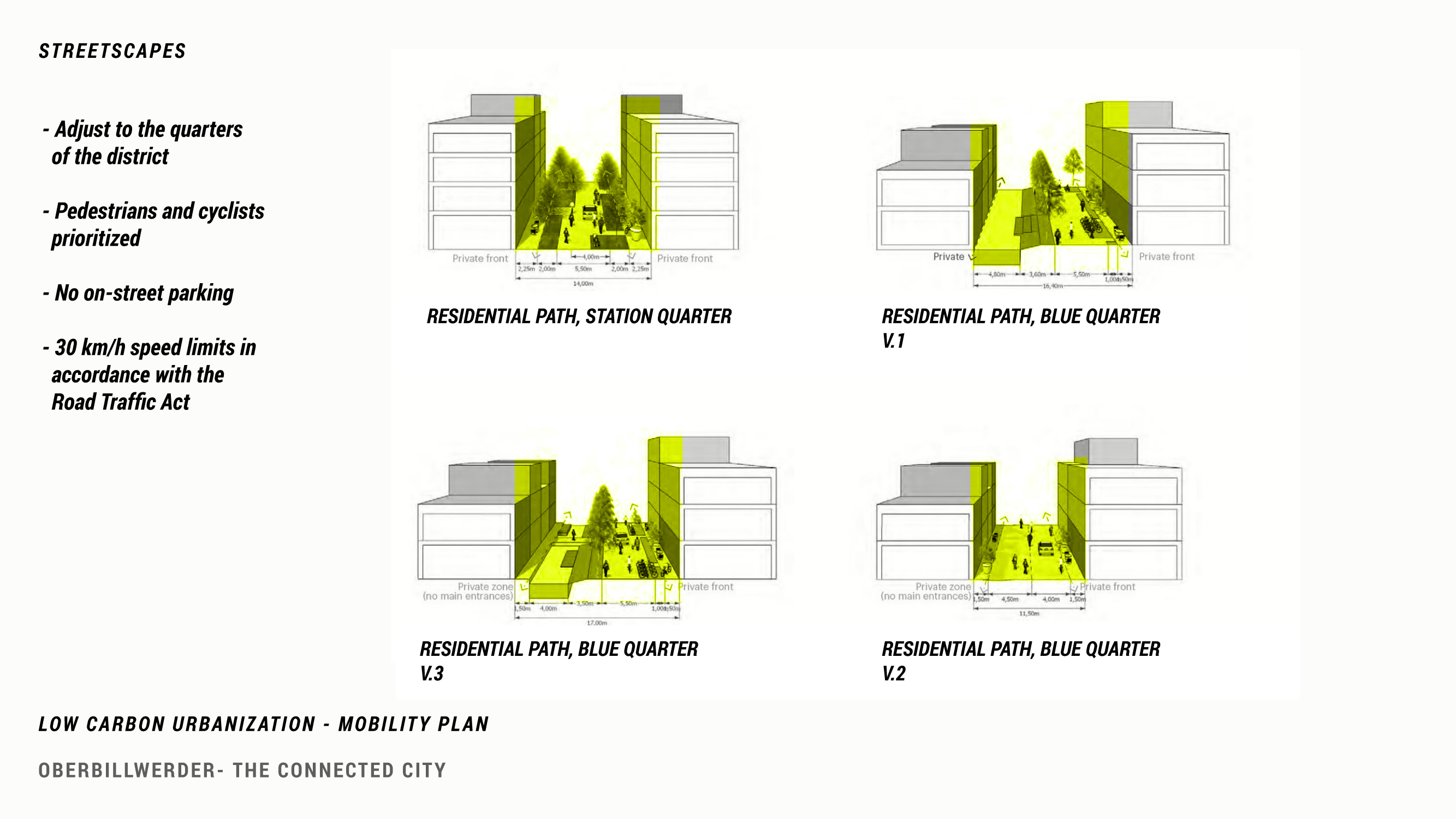

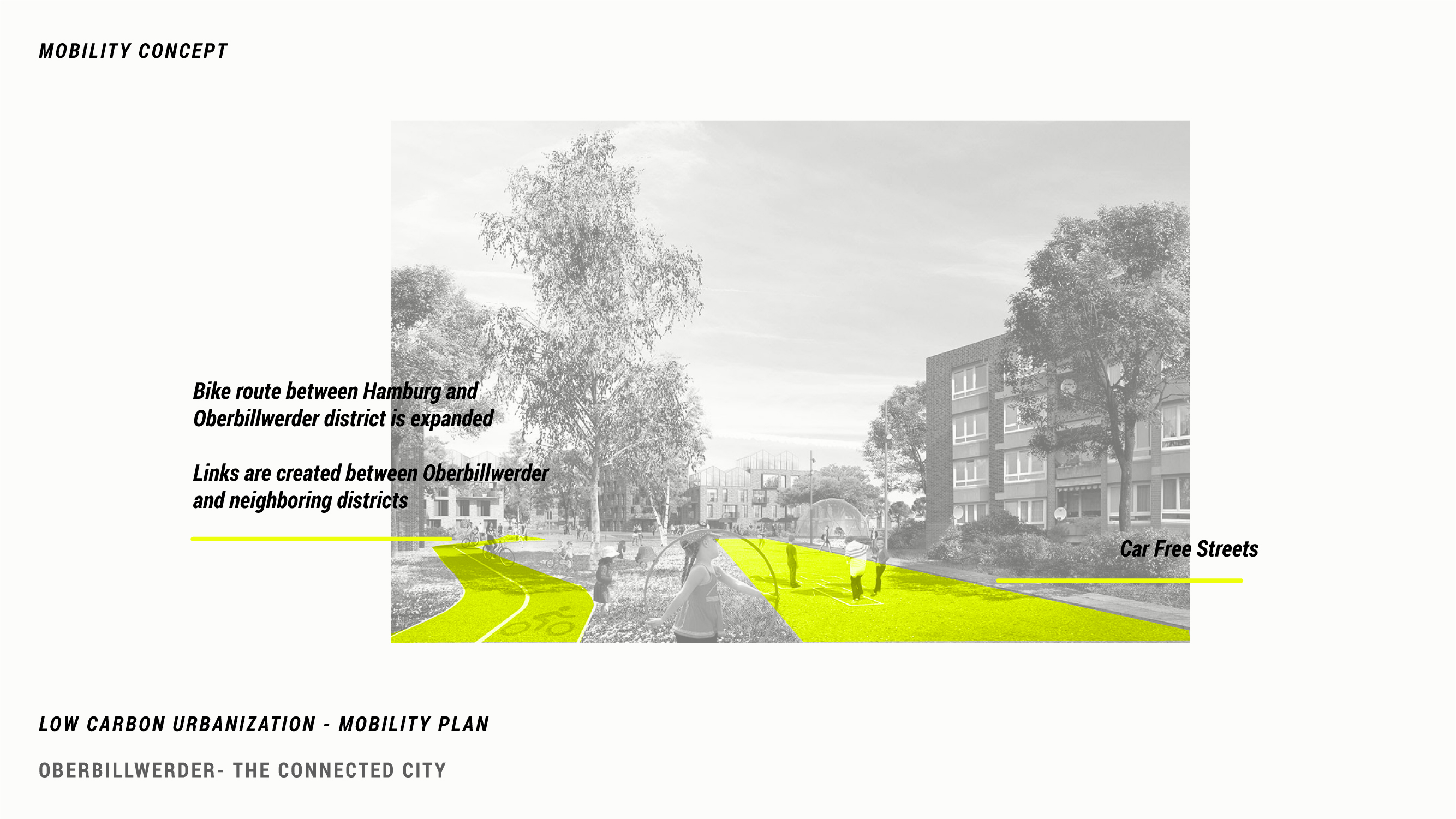

The design integrates residential development, including some affordable housing, with retail, commercial, recreational opportunities, and a regional connection to the city center. The project emphasizes self-reliant energy production such as orienting buildings to take advantage of natural sunlight—a design technique called heliomorphism. Within each neighborhood, climate adaptation techniques—including wide canals, rain beds to absorb overflow, linear trenches on the sides of streets, and concavely graded street profiles—are used to protect buildings from flooding. While the project is located outside of the center of Hamburg, a series of green arteries that prioritize pedestrians and cyclists link Oberbillwerder to the city center. Despite some resistance to the development by neighboring residents, the masterplan has been approved by the district and city governments and IBA Hamburg has begun preparing what is currently agricultural land for its new use.

The following description of the Connected City masterplan is divided into four sections. The first section places the Connected City initiative within a legacy of master planning at the urban periphery. The second section is an overview of the city of Hamburg, its recent history and the conception of the Oberbillwerder district and design competition. The third section evaluates key “low-carbon” aspects of the Connected City proposal’s urbanization plans. The final section raises/discusses some larger challenges and debates that the Connected City proposal does not address, intentionally or otherwise.

The design integrates residential development, including some affordable housing, with retail, commercial, recreational opportunities, and a regional connection to the city center. The project emphasizes self-reliant energy production such as orienting buildings to take advantage of natural sunlight—a design technique called heliomorphism. Within each neighborhood, climate adaptation techniques—including wide canals, rain beds to absorb overflow, linear trenches on the sides of streets, and concavely graded street profiles—are used to protect buildings from flooding. While the project is located outside of the center of Hamburg, a series of green arteries that prioritize pedestrians and cyclists link Oberbillwerder to the city center. Despite some resistance to the development by neighboring residents, the masterplan has been approved by the district and city governments and IBA Hamburg has begun preparing what is currently agricultural land for its new use.

The following description of the Connected City masterplan is divided into four sections. The first section places the Connected City initiative within a legacy of master planning at the urban periphery. The second section is an overview of the city of Hamburg, its recent history and the conception of the Oberbillwerder district and design competition. The third section evaluates key “low-carbon” aspects of the Connected City proposal’s urbanization plans. The final section raises/discusses some larger challenges and debates that the Connected City proposal does not address, intentionally or otherwise.

Organizations & Collaborators

Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg, State Ministry of Urban Development and Housing (Client)

Bergedorf District Office (Client)

IBA Hamburg GmbH (Project Development)

ADEPT (Architect)

Karres en Brands (Landscape Architect)

Transsolar (Engineer)

Bergedorf District Office (Client)

IBA Hamburg GmbH (Project Development)

ADEPT (Architect)

Karres en Brands (Landscape Architect)

Transsolar (Engineer)

Key Terms

THE URBAN MASTERPLAN

- DREAMS OF THE GREEN SUBURB

Urban planners have long sought to reconcile/integrate city life and exurban landscapes. Two well-known plans for the extension of the city into the surrounding countryside have been Ebenezer Howard’s “Garden City” concept (1898) and Frank Lloyd Wright’s “Broadacre City” plan/concept/design (1932). Howard imagined a walkable city extending from a central green and in which homes that looked onto shared open spaces were further surrounded by agricultural production. These cities, which Howard diagrammed as radial plans, would be connected to each other and to economic, urban centers by rail networks.

A few decades later, Frank Lloyd Wright’s “Broadacre City” vision sought to integrate open space and agricultural production but gave priority to the individually owned automobile in his plan, in many ways predicting the eventual American exurbanization of the latter half of the twentieth century (Nelson, 1995). In the Broadacre plan, each household would be allotted a minimum of one acre of land on which homes would be built and agricultural produce cultivated. Wright expected each family to own a car, which residents would use to reach public services, amenities, and larger roadways.

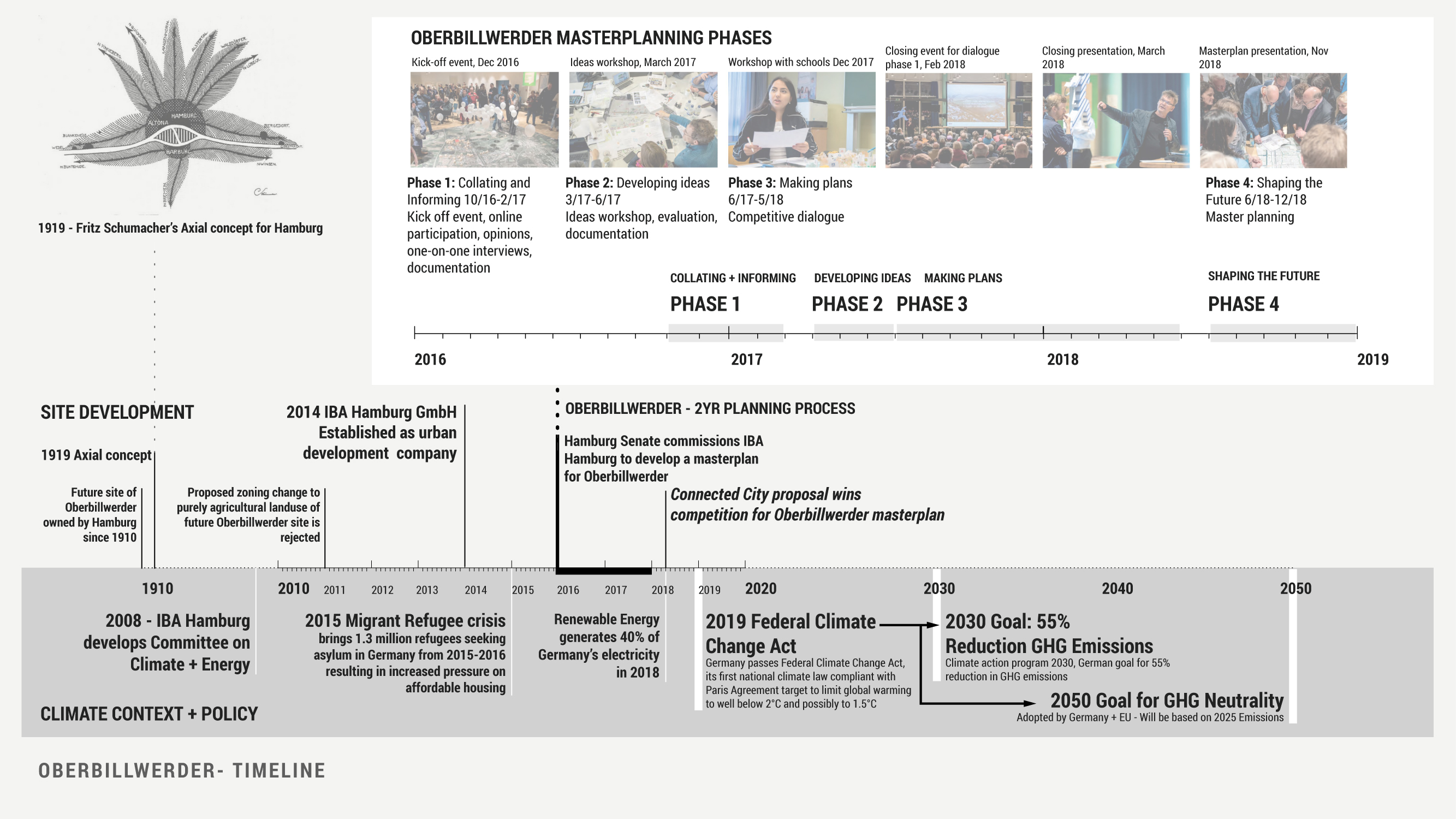

As English planners and architects attempted to give form to Howard’s Garden City in the early twentieth century, similar experiments were taking place in Germany, including the first German “garden city” in Dresden Hellerau (1909). Instrumental to, yet critical of, that plan was the architect and planner Fritz Schumacher, who also created masterplans for the cities of Cologne and Hamburg (1919). Schumacher, like Howard, was skeptical of existing patterns of urbanization and his plan for Hamburg was as much, if not more, about the city’s periphery as it was its center (Schubert, 2020). His designs, based on the city’s topography and soil conditions, established radiating rings of landscape from the countryside to the city, many of which are still evident in contemporary Hamburg.

The Connected City masterplan can be viewed within this same lineage, as a landscape-forward design built on agricultural land at the urban periphery. It, too, focuses on connections to the city center and surrounding communities, interior mobility, and the relationship and integration with new and existing open space and agricultural production. But unlike its predecessors, the Connected City puts climate change and low-carbon design at the center of its plan and explicitly engages the site’s environmental realities, especially increased rain and flooding. While it reveals an appreciation for its site, the masterplan’s futurist ethos also runs the risk of regarding the space on which it will build Oberbillwerder as a tabula rasa, or blank slate, upon which existing conditions can be easily neglected or overrun. Finding the balance between designing for the future and maintaining continuity and respect of the existing character of an area will be challenging.

HAMBURG

Out of this work, the city created a new model for their urban development. In 1998, the government of Hamburg formed a subsidiary company (GHS Gesellschaft für Hafen und Standortentwicklung mbH, now HafenCity Hamburg GmbH) to manage the development of a new waterfront neighborhood called HafenCity. The subsidiary is owned by and operates under the legal authority of the Hamburg government but is privately run, giving its executive board freedom to act outside of the timelines and structures of traditional bureaucracy. Much of the organization’s work has been dedicated to the creation, amendment, and implementation of a masterplan that places particular emphasis on meeting bold climate standards set by Germany and the European Union. HafenCity’s design focused on both mitigation and adaptation, through energy efficiency and transit and reducing flood risk and urban heat island impacts. To attract some of Europe’s most accomplished design firms, the city invested heavily in the competition process and request for proposals and subsidized the private sector’s investment in new construction that follows the guidelines of the masterplan.

In 2006, when residents of the island district Wilhelmsburg asked to be considered as a site for investment and bold visioning, the city returned to their HafenCity model to spark new development. They created the subsidiary IBA Hamburg GmbH to develop an international building exhibition that would host model forms of design and construction in Wilhelmsburg. The aim for the exhibition was to attract private investment by supporting new ideas in the building, design, and construction trades, in particular innovative responses to climate change. The exhibition (also titled IBA Hamburg) was in development for seven years, officially opening alongside an international garden show in 2013 and ultimately attracting 420,000 visitors to Wilhelmsburg and €700 million of private investment combined with €300 million of public investment. The perceived success of IBA Hamburg led to the government expanding the responsibilities of the management company to include the continued development of Wilhelmsburg. And unlike HafenCity Hamburg GmbH, who are responsible for a single district, IBA Hamburg GmbH has become the government’s management organization for several subsequent large-scale mixed-use developments.

The most recent of these projects is the district of Oberbillwerder, a collection of city-owned agricultural plots that sits approximately twenty minutes outside the city center by rail. IBA Hamburg initiated an EU-wide competition to develop a masterplan for this area, which the city deemed would become a new administrative district. The organization ran a multi-level community engagement process as part of the competition, asking chosen teams to participate in various community meetings before submitting their projects and ultimately selecting a winner: a team led by the Copenhagen-based design and planning office ADEPT with landscape architects Karres en Brands from Hilversum, Netherlands, and engineers Transsolar, based in Stuttgart, Germany.

LOW CARBON URBANIZATION

ENERGY

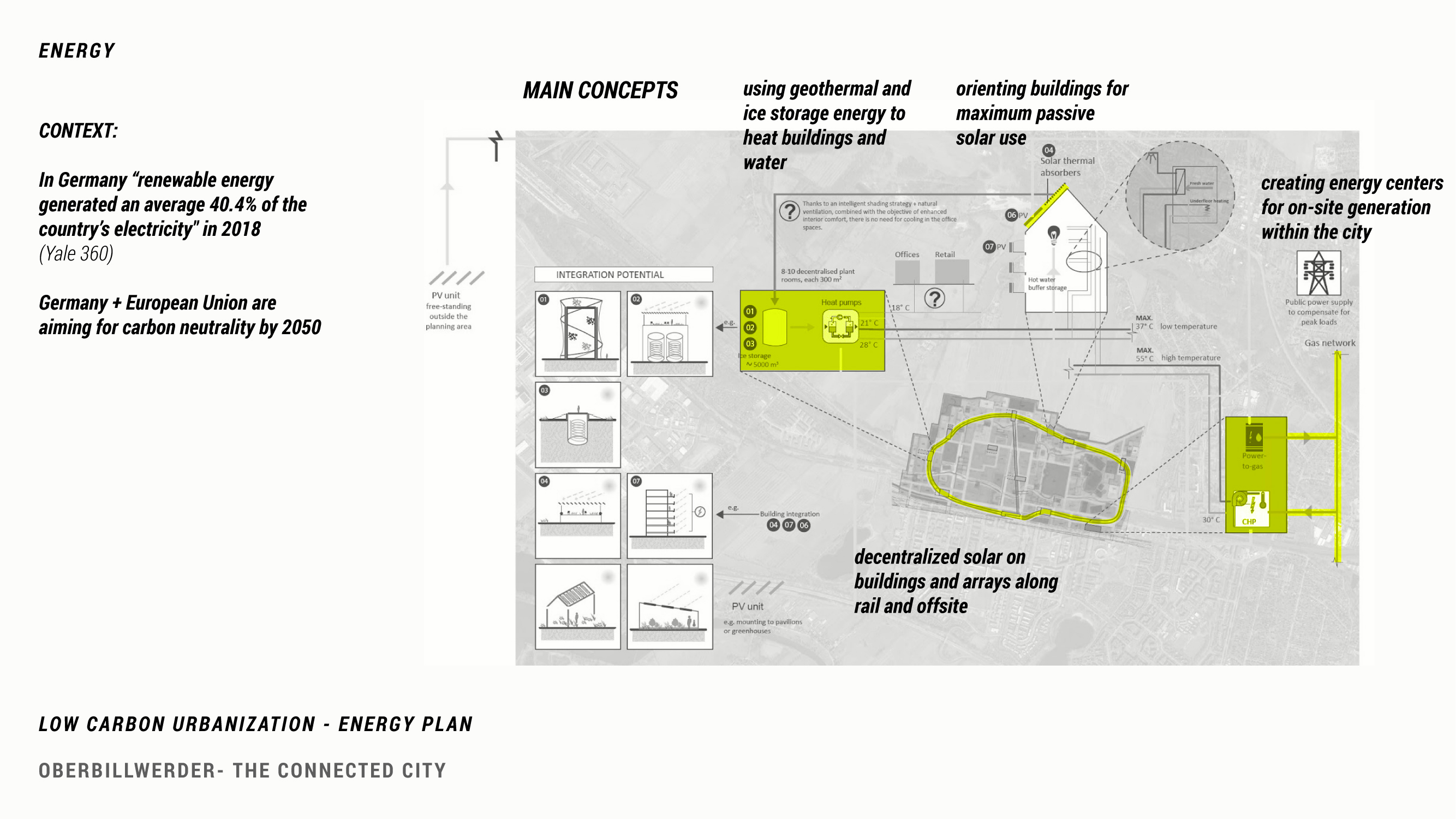

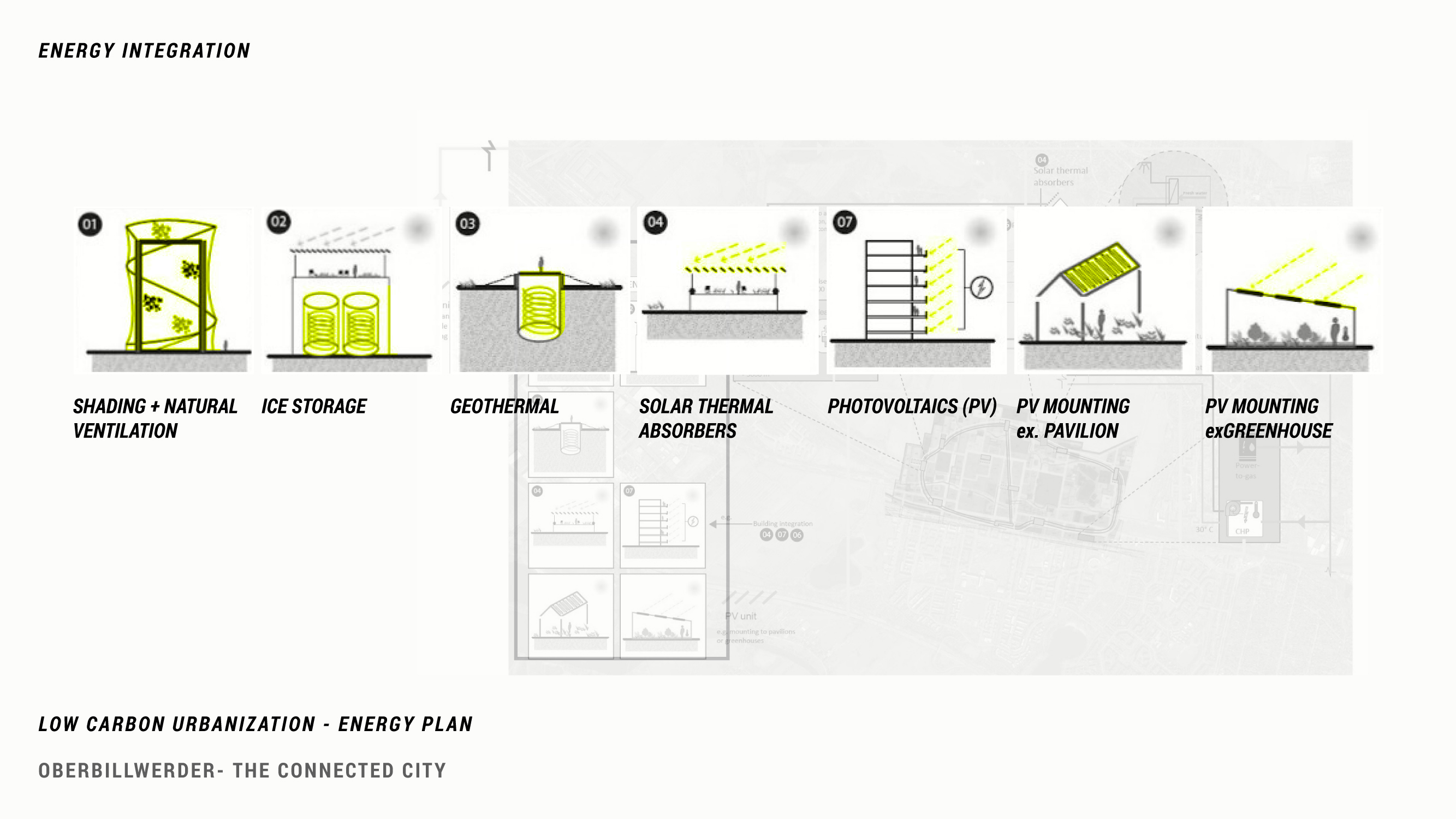

The Connected City proposal aims to make its energy supply “mostly carbon neutral,” but as of late 2020 no details about the district’s projected energy demands and its plans to meet that demand in a carbon neutral manner are available. General concepts that the Connected City will follow include: orienting buildings to maximize passive solar gain; installing a decentralized photovoltaic system that draws from panels on rooftops, along rail lines, and from off-site arrays; using geothermal energy to heat and cool buildings; and creating energy centers capable to generating electricity at small hubs within the city (IBA Hamburg 2019).

CLIMATE-FORWARD MOBILITY

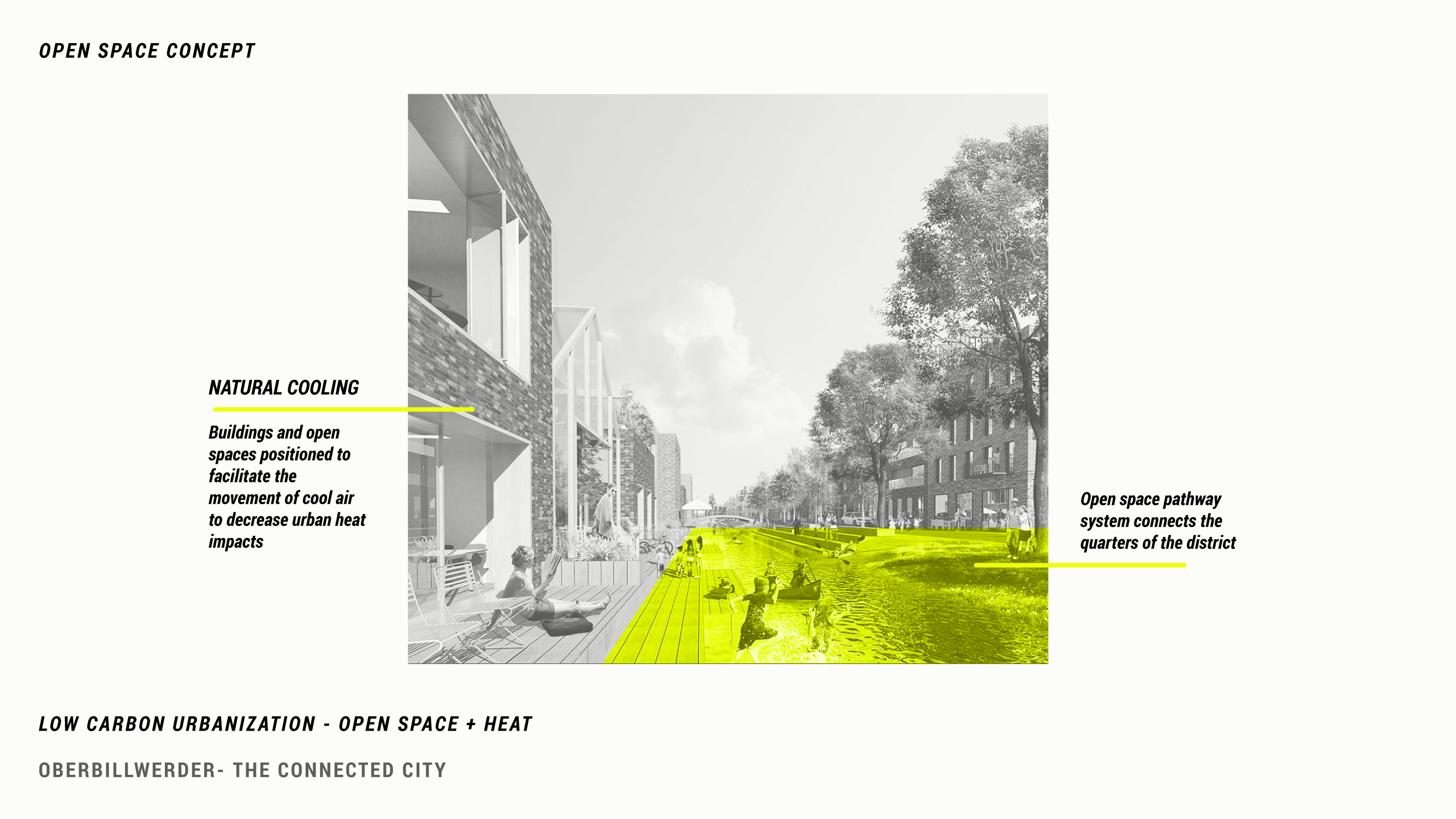

OPEN SPACE AND HEAT

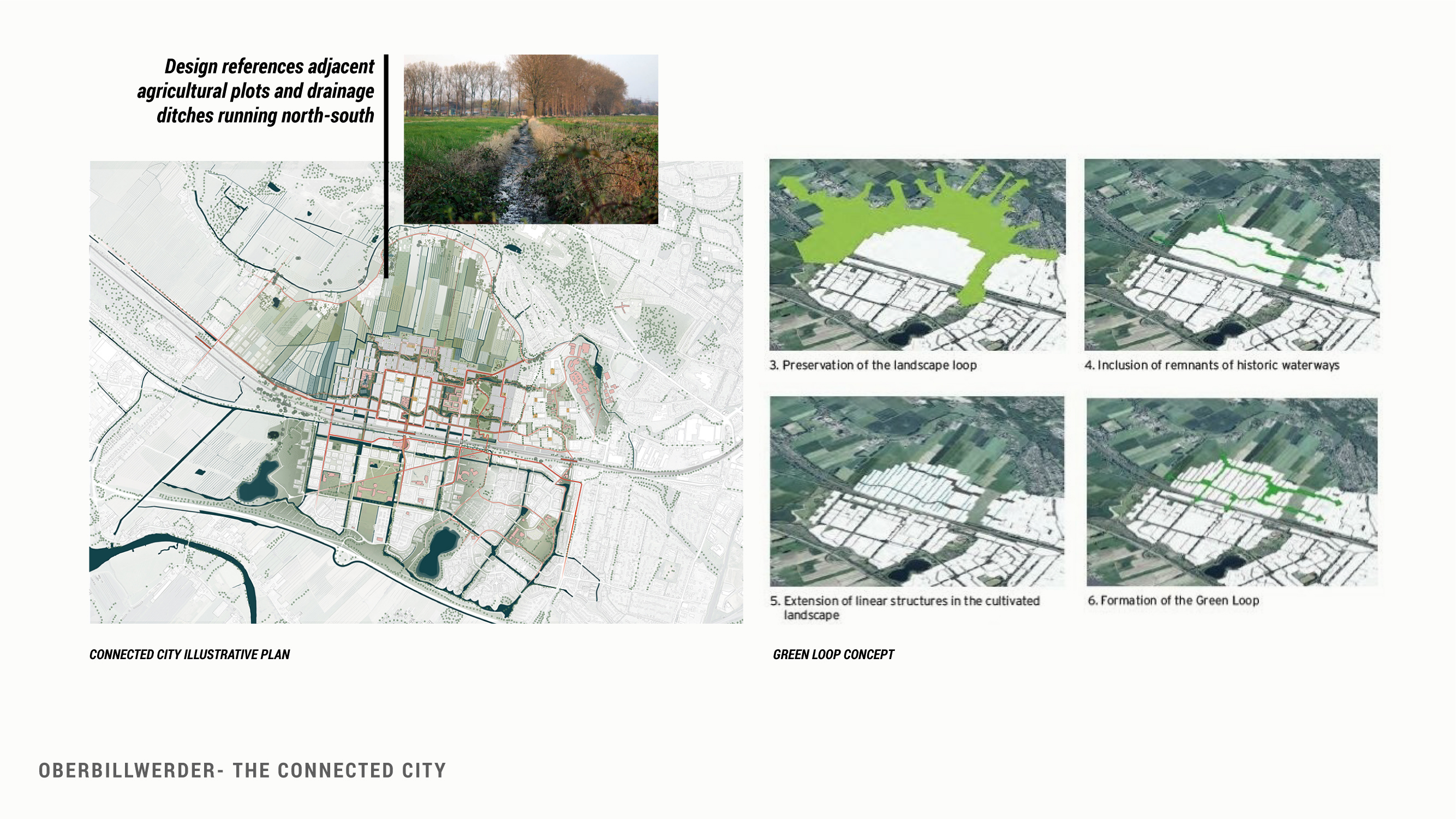

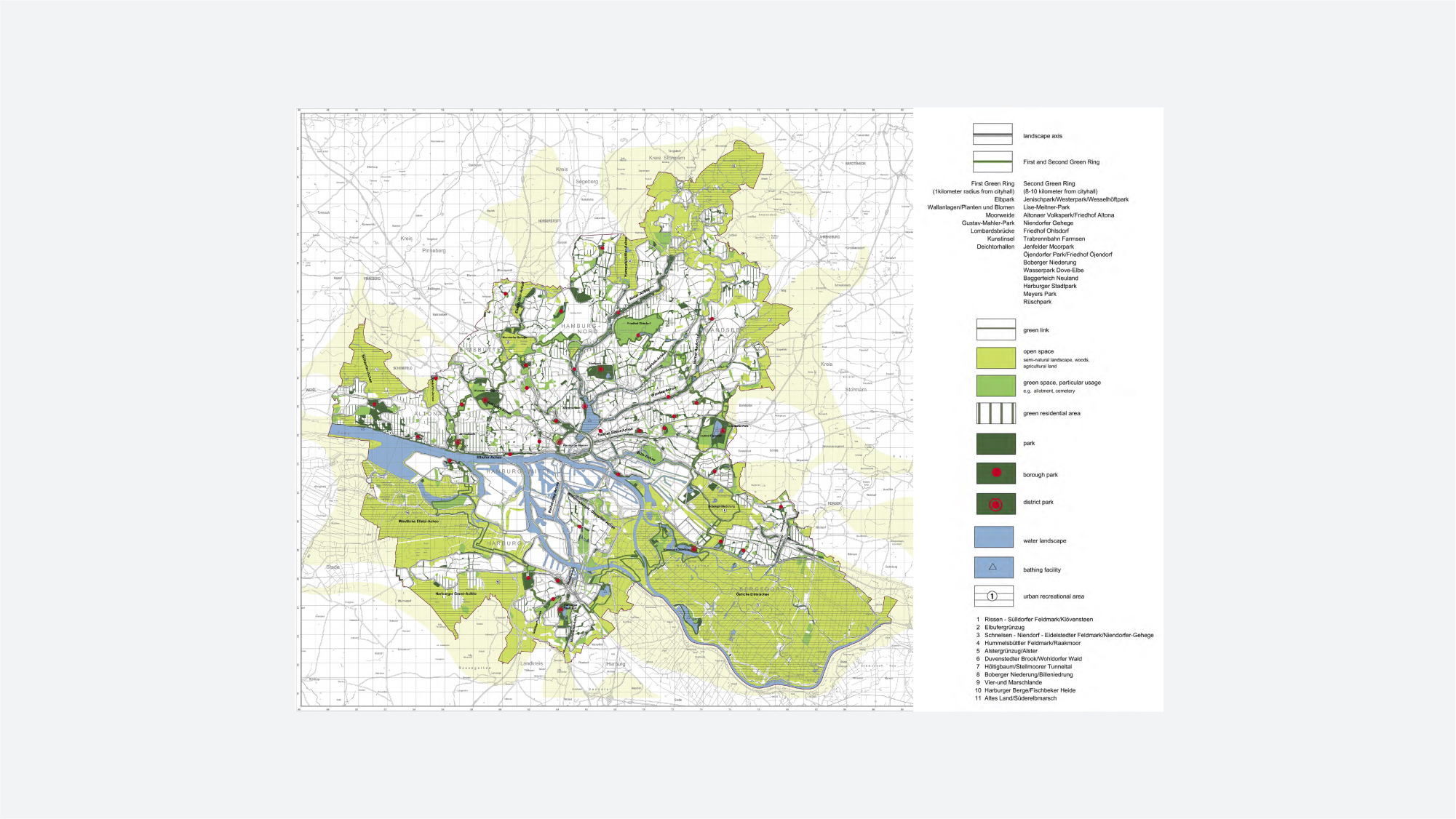

Hamburg’s current open space planning follows in the city's tradition of planning for growth. In 1919, city planner Fritz Schumacher devised a plan for Hamburg’s expansion, concentrating development along axes that followed the “high and dry” lands, while open space and agricultural land was located in the city’s marshy lowlands (Schubert 2020). After WWII, the city devised a green ring system that circumscribed the urban center in parks, recreational open spaces and agricultural land. This plan is now known as the GrunesNetsHamburg. Oberbillwerder, the site of the Connected City plan, lies just outside this green network.

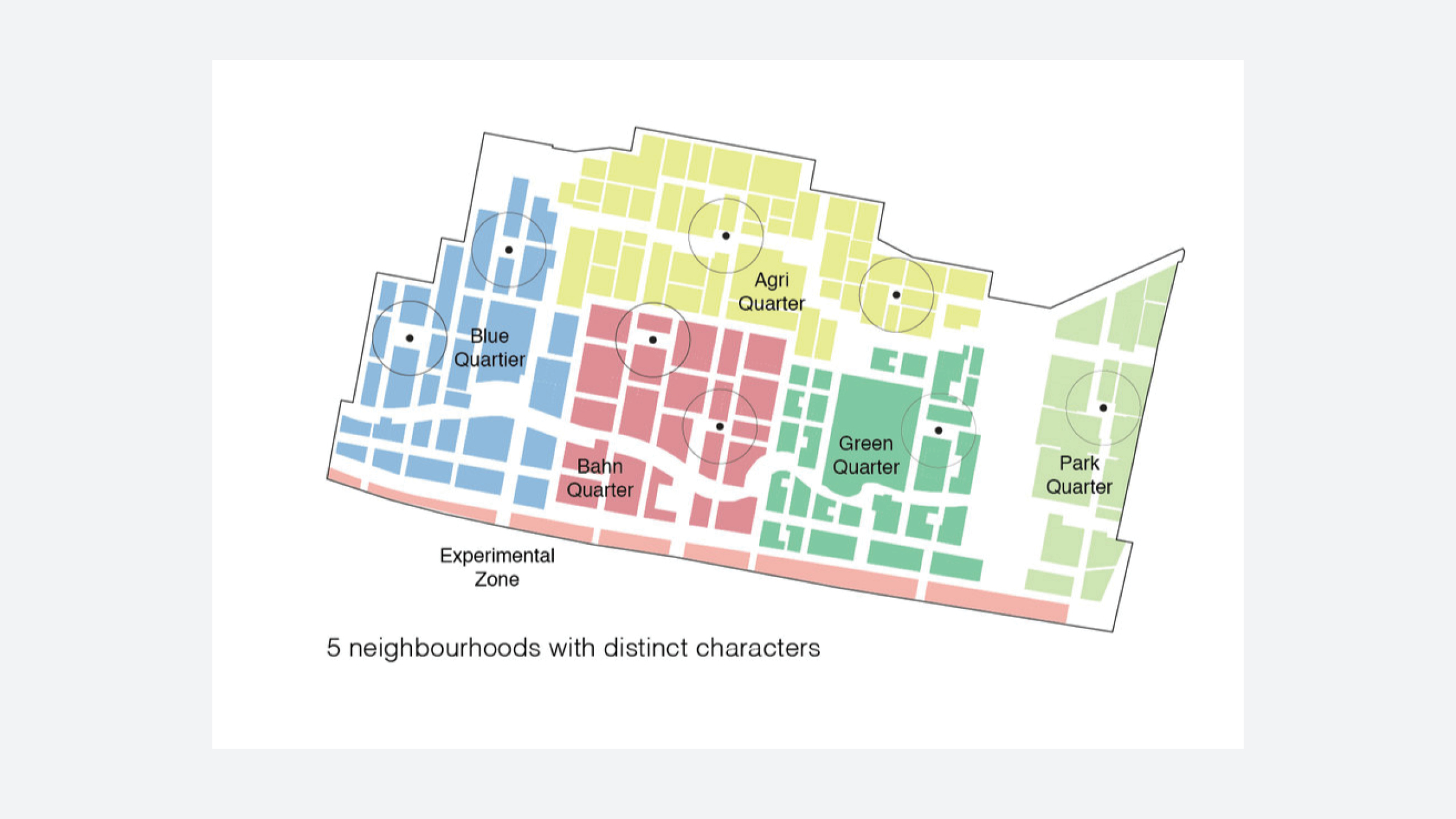

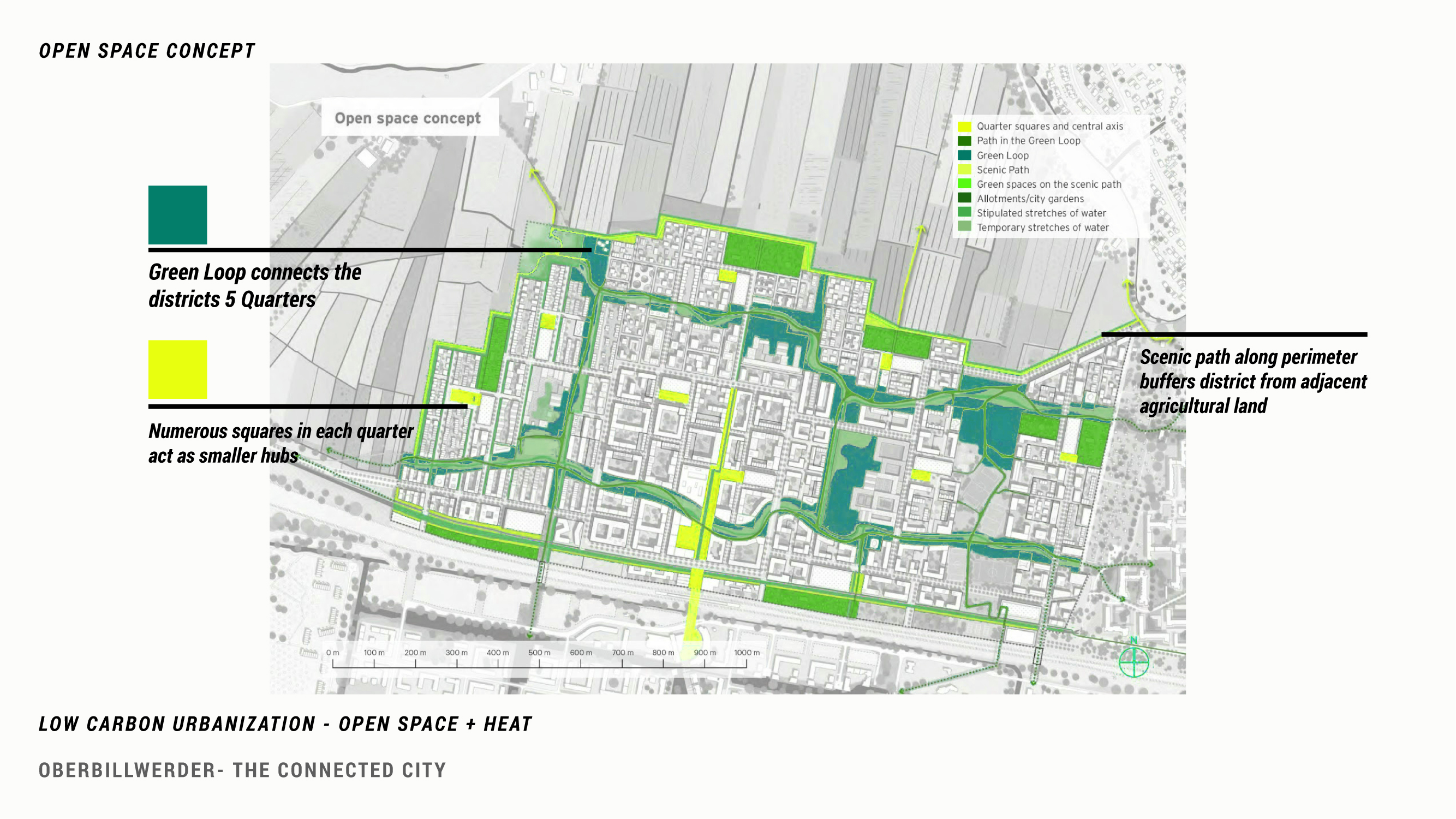

The Connected City proposes its own green loop that structures the district and connects the five sections. The proposal’s open spaces bridge, connect, and cool the city. Public squares, which will be found in all neighborhoods/quarters/areas serve as secondary open spaces and will also serve as localized hubs for transit, cultural programming, and other resources. Six hectares of land will be set aside for small scale agricultural allotments, which will provide residents their own space to garden within the city. The edges of the city will be buffered by open space in order to create a ‘landscape corridor’ between two existing nature preserves on the edge of the district. All of these spaces are carefully arranged in coordination with buildings and structures to facilitate the movement of cool air in order to decrease the impacts of the urban heat island effect.

The Connected City proposes its own green loop that structures the district and connects the five sections. The proposal’s open spaces bridge, connect, and cool the city. Public squares, which will be found in all neighborhoods/quarters/areas serve as secondary open spaces and will also serve as localized hubs for transit, cultural programming, and other resources. Six hectares of land will be set aside for small scale agricultural allotments, which will provide residents their own space to garden within the city. The edges of the city will be buffered by open space in order to create a ‘landscape corridor’ between two existing nature preserves on the edge of the district. All of these spaces are carefully arranged in coordination with buildings and structures to facilitate the movement of cool air in order to decrease the impacts of the urban heat island effect.

CONCLUSION

Since the new district will be built on former agricultural land, there is seen to be an opportunity to fully reimagine urban systems and connections with the goal of promoting “low carbon living.” The Connected City proposal is in many ways a utopian vision, driven by the hope that if the systems that sustain urban life were designed more efficiently (energy, mobility, waste, housing), there would be no need to fully disrupt or change existing ways of life. The Connected City approach is also utopian in its insularity – the proposal materials do not confront some larger pressures on Hamburg in particular and on Germany generally.

One example of this relates to Germany’s refugee population. Germany has one of the highest refugee populations of any nation worldwide. After a large influx of asylum seekers in 2014, Hamburg rushed to build “follow up” housing—new housing stock intended for immigrants who were granted asylum but could not find any affordable accommodation. Hamburg was the only German state to create a refugee housing authority, and other states have looked to the city as they consider creating a similar agency. Today, Hamburg’s “follow up” housing program expansion has slowed, but the need for housing for vulnerable populations remains. Will the Connected City include “follow up” housing and other support services meant for asylum seekers? The current proposal does not explicitly engage this issue.

The proposal understates the challenges to converting agricultural land into a new urban district, perhap implying this transition was inevitable. In 2019, a local group of residents and activists started a campaign called “No to Oberbillwerder,” advocating against the district’s rezoning, hoping to preserve the land. The group argues that developing land that is currently agricultural fields, stables, and nature preserves is fundamentally bad for the local and global environment. While the claims of the “No to Oberbillwerder” group are not untrue—the development strips away open space, plant and animal habitats, and long embedded agricultural practices—the project also brings housing and transportation access to a rapidly growing and housing-stressed city.

This form of resistance to new development falls in line with a longer lineage of “Not In My Back Yard” (NIMBY) activism. NIMBYism is the fear or antipathy toward changes to one’s community or general status quo. These NIMBY fears are often marked by race and class prejudice, presenting a fear of changing neighborhood demographics. Environmental protection has long been a concept wielded by NIMBY groups to stop changes that may pose a threat to the status quo (Dougherty 2020, 80-83). Oberbillwerder is no exception. Residents also argue that Hamburg would be better served by adding density in its urban center rather than carving away at open space. These concerns likely come out of a lack of clarity in the planning process, raising questions about how and why Oberbillwerder was chosen to develop. Is it to provide needed housing? Or to advance a model of low-carbon city making? Is inner Hamburg too dense to develop further, or simply too expensive?

These questions reflect the many complexities that are obscured by the materials put forth by the City of Hamburg. These concerns are common throughout many “masterplan” developments globally that seek to address climate mitigation through ambitious blank-slate models for urban life.

One example of this relates to Germany’s refugee population. Germany has one of the highest refugee populations of any nation worldwide. After a large influx of asylum seekers in 2014, Hamburg rushed to build “follow up” housing—new housing stock intended for immigrants who were granted asylum but could not find any affordable accommodation. Hamburg was the only German state to create a refugee housing authority, and other states have looked to the city as they consider creating a similar agency. Today, Hamburg’s “follow up” housing program expansion has slowed, but the need for housing for vulnerable populations remains. Will the Connected City include “follow up” housing and other support services meant for asylum seekers? The current proposal does not explicitly engage this issue.

The proposal understates the challenges to converting agricultural land into a new urban district, perhap implying this transition was inevitable. In 2019, a local group of residents and activists started a campaign called “No to Oberbillwerder,” advocating against the district’s rezoning, hoping to preserve the land. The group argues that developing land that is currently agricultural fields, stables, and nature preserves is fundamentally bad for the local and global environment. While the claims of the “No to Oberbillwerder” group are not untrue—the development strips away open space, plant and animal habitats, and long embedded agricultural practices—the project also brings housing and transportation access to a rapidly growing and housing-stressed city.

This form of resistance to new development falls in line with a longer lineage of “Not In My Back Yard” (NIMBY) activism. NIMBYism is the fear or antipathy toward changes to one’s community or general status quo. These NIMBY fears are often marked by race and class prejudice, presenting a fear of changing neighborhood demographics. Environmental protection has long been a concept wielded by NIMBY groups to stop changes that may pose a threat to the status quo (Dougherty 2020, 80-83). Oberbillwerder is no exception. Residents also argue that Hamburg would be better served by adding density in its urban center rather than carving away at open space. These concerns likely come out of a lack of clarity in the planning process, raising questions about how and why Oberbillwerder was chosen to develop. Is it to provide needed housing? Or to advance a model of low-carbon city making? Is inner Hamburg too dense to develop further, or simply too expensive?

These questions reflect the many complexities that are obscured by the materials put forth by the City of Hamburg. These concerns are common throughout many “masterplan” developments globally that seek to address climate mitigation through ambitious blank-slate models for urban life.

SOURCES

ADEPT. “Oberbillwerder.” https://www.adept.dk/project/oberbillwerder-the-connected-city.

Beyers, Bert. “Neuer Stadtteil Oberbillwerder: Aus Fehlern lernen?” Hamburg Journal - NDR. 21 July 2020. https://www.ndr.de/nachrichten/hamburg/Neuer-Stadtteil-Oberbillwerder-Aus-Fehlern-lernen,oberbillwerder190.html.

Charpentier, Mathilde. “IBA Hamburg, a German Approach on Sustainable Urban Development.” Construction 21 International. 25 May 2015. https://www.construction21.org/articles/h/iba-hamburg-a-german-approach-on-sustainable-urban-development.html.

The Connected City: Oberbillwerder Masterplan. Hamburg: IBA Hamburg GmbH, 2019.

Dougherty, Conor. Golden Gates: Fighting for Housing in America. Penguin Press, 2020.

“Green Network.” Hamburg.com. https://www.hamburg.com/residents/green/11836450/green-network.

HafenCity Hamburg. “Glossary.” HafenCity Hamburg GmbH. https://www.hafencity.com/en/glossary.html.

Hockenos, Paul. “Carbon Crossroads: Can Germany Revive Its Stalled Energy Transition?” Yale E360. Yale School of the Environment, December 13, 2018. https://e360.yale.edu/features/carbon-crossroads-can-germany-revive-its-stalled-energy-transition.

Howard, Ebenezer. Garden Cities of To-morrow. England: S. Sonnenschein & Co., Ltd., 1902. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015055593399.

IBA_Hamburg. “Glossary.” IBA Hamburg GmbH. https://www.iba-hamburg.de/en/services/glossary.

IBA_Hamburg – International Building Exhibition IBA Hamburg 2006-2013. IBA Hamburg GmbH. https://www.internationale-bauausstellung-hamburg.de.

IBA_Hamburg. “Oberbillwerder.” IBA Hamburg GmbH. https://www.iba-hamburg.de/en/projects/oberbillwerder/overview.

“Naturparadies Oberbillwerder,” 2019. https://nein-zu-oberbillwerder.jimdofree.com/oberbillwerder/.

Nelson, Arthur C. “The Planning of Exurban America: Lessons from Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 12, 4 (Winter, 1995): 337-356.

“Renewables Generated a Record 65 Percent of Germany's Electricity Last Week.” Yale E360, March 13, 2019. https://e360.yale.edu/digest/renewables-generated-a-record-65-percent-of-germanys-electricity-last-week.

Scheffler, Nils. “Case Study - Cities Tackling Climate Change: The Case of the International Building Exhibition (IBA) Hamburg.” Urbact II Capitalisation, April 2015. Saint Denis, France: URBACT, 2015.

Schubert, Dirk. “Fritz Schumacher - Neglected German Town Planner and Urban Reformer in Hamburg and Cologne.” Planning Perspectives (May 2020, online ahead of print). https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2020.1757497.

Transsolar. “Oberbillwerder Masterplan, Hamburg, Germany.” https://transsolar.com/projects/hamburg-oberbillwerder-masterplan.

“U.S. Energy Information Administration - EIA - Independent Statistics and Analysis.” U.S. renewable electricity generation has doubled since 2008 - Today in Energy - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), March 19, 2019. https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=38752.

Wehrmann, Benjamin. “Wind Provides Half of Germany's Power for a Whole Week,” March 12, 2019. https://www.cleanenergywire.org/news/wind-provides-half-germanys-power-whole-week.

Wright, Frank Lloyd. “Broadacre City: A New Community Plan.” Architectural Record 77 (April 1935): 243–252.