INFORM@RISK

Overview

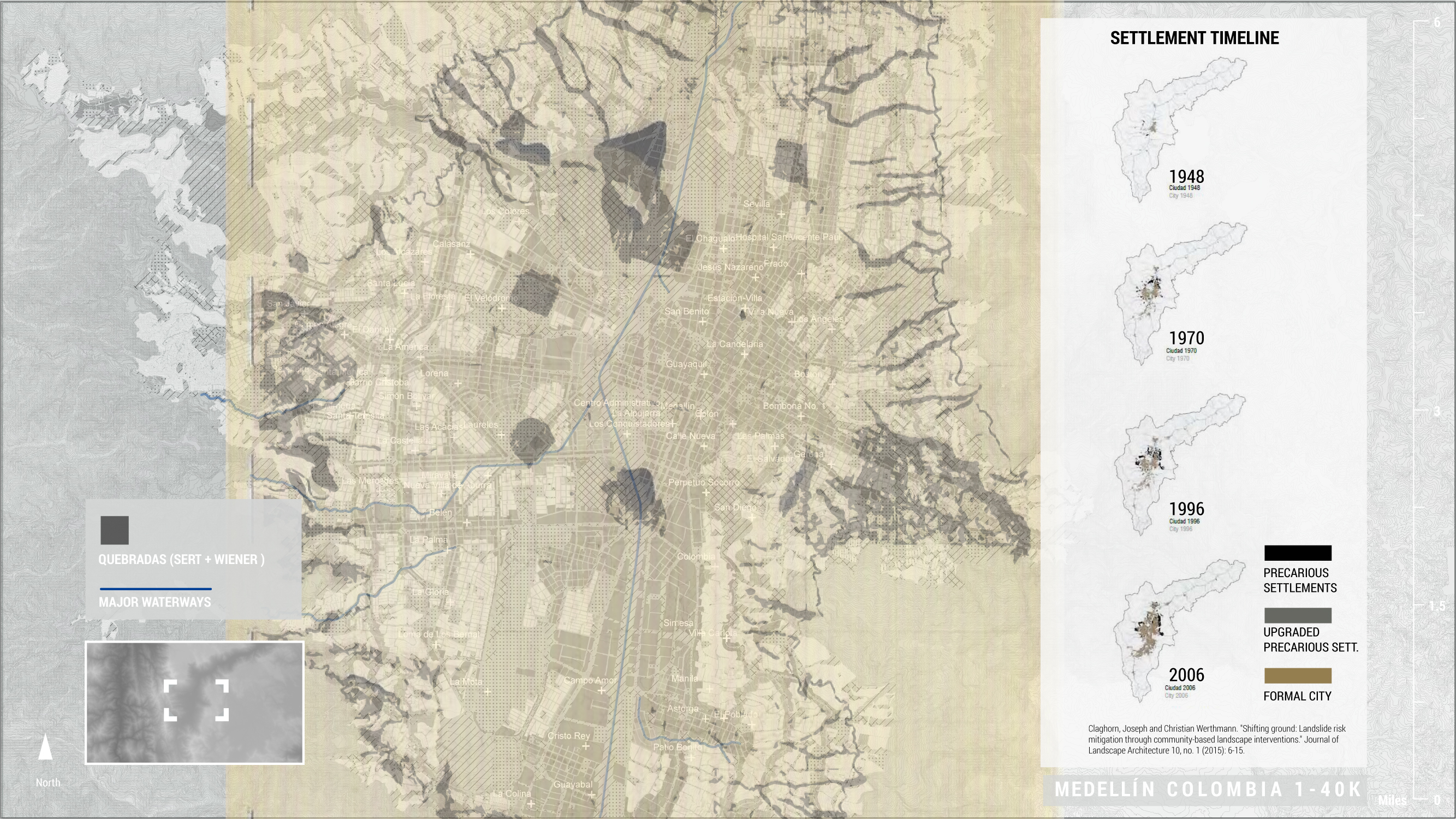

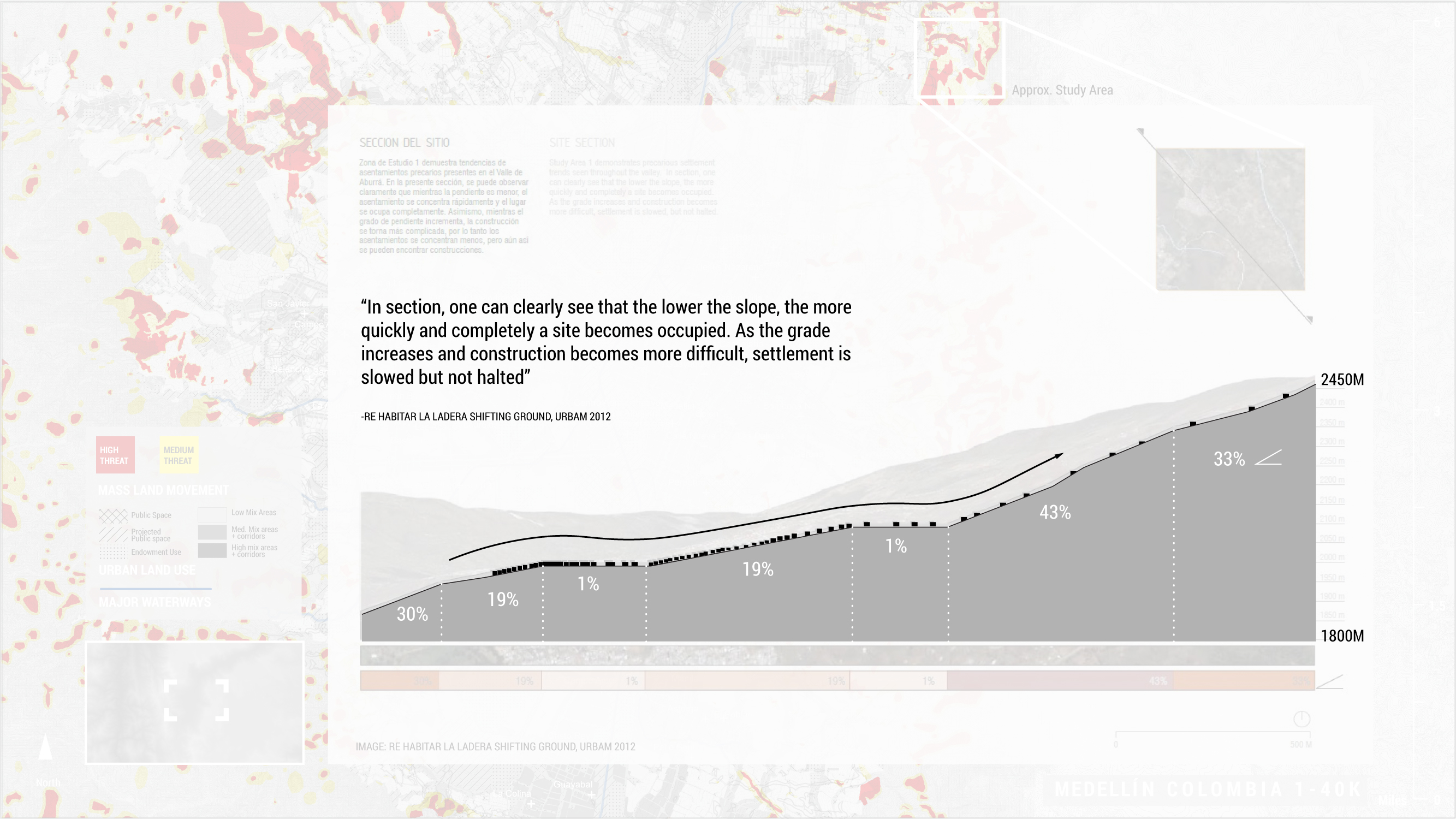

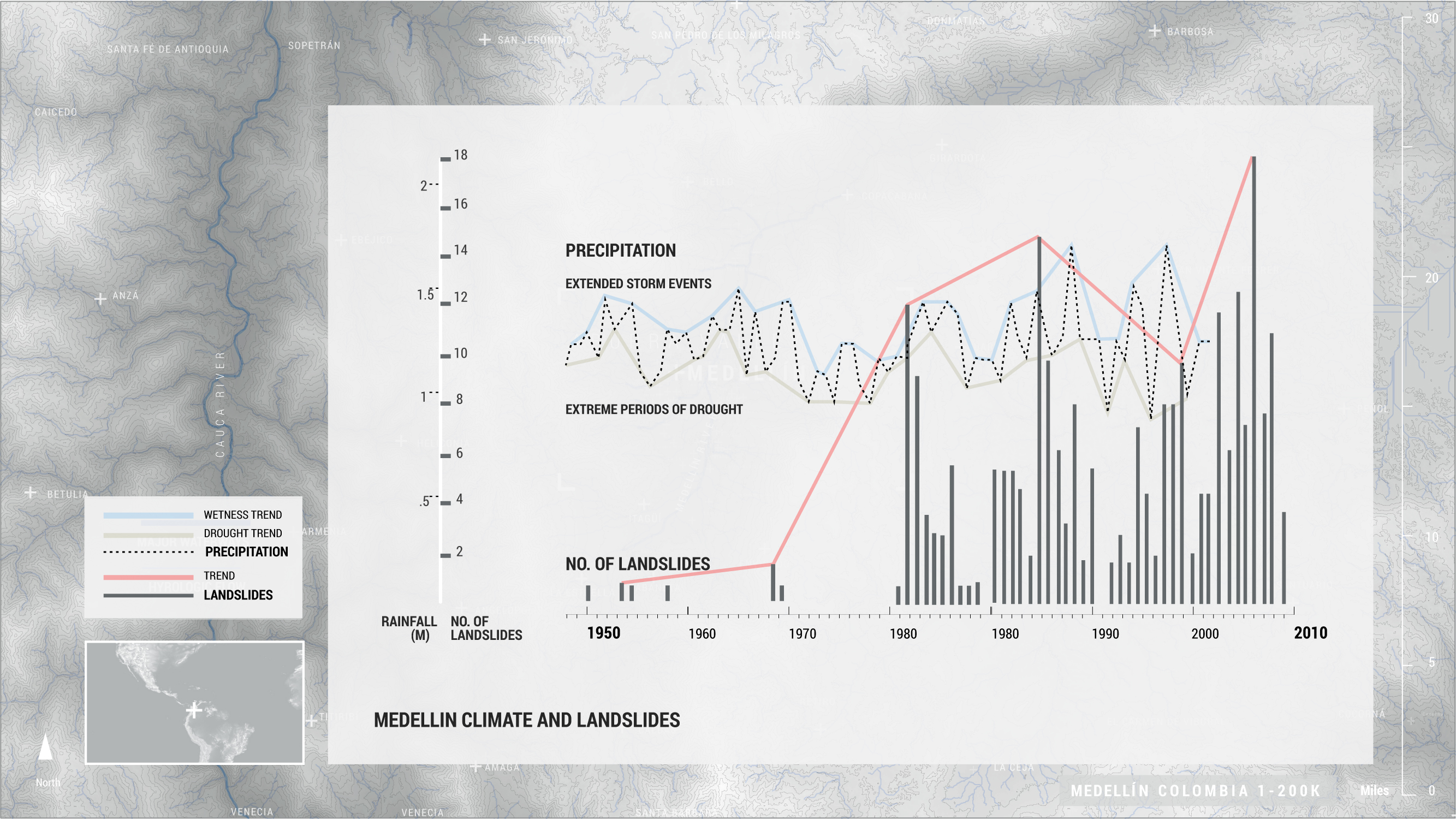

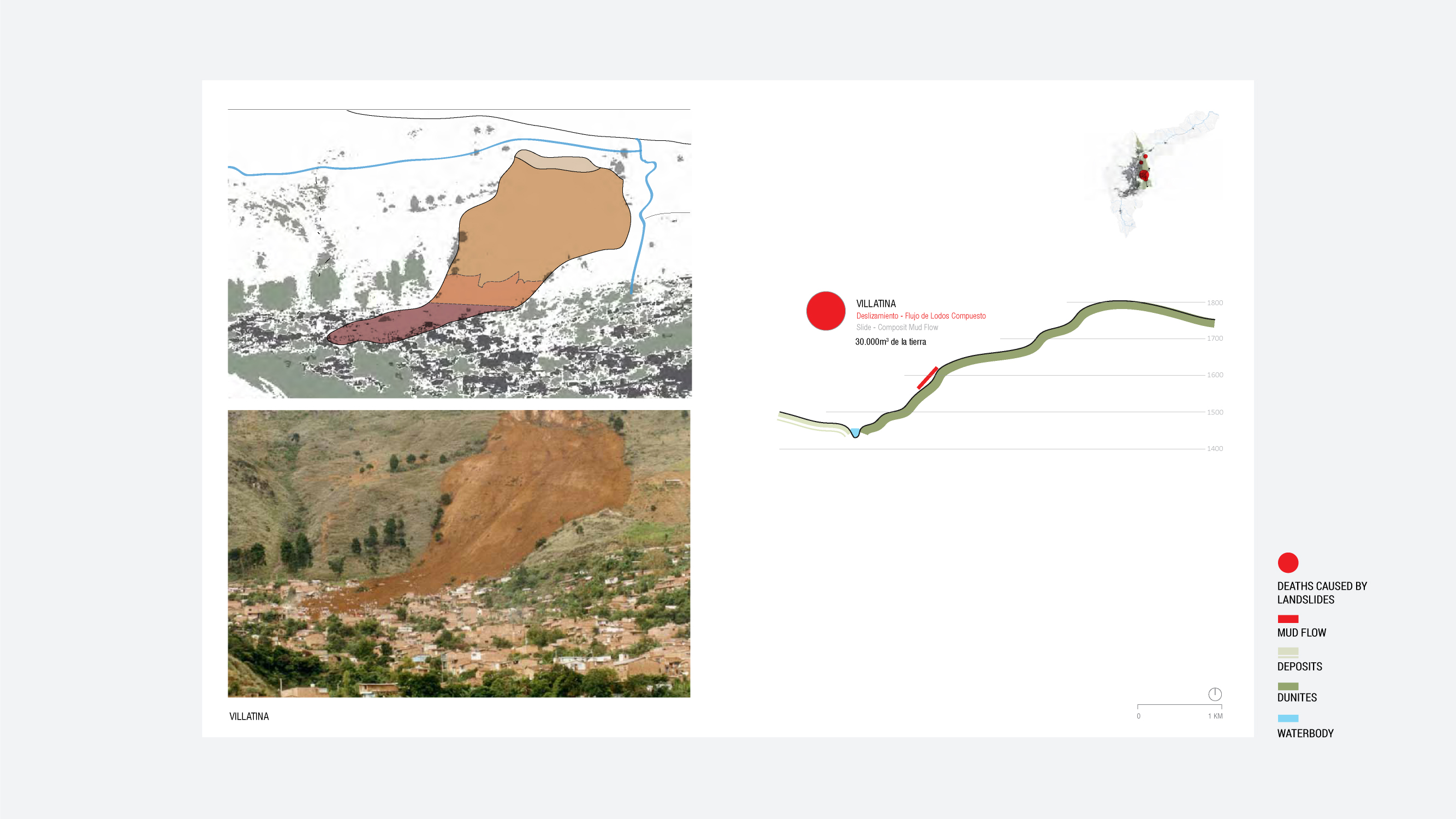

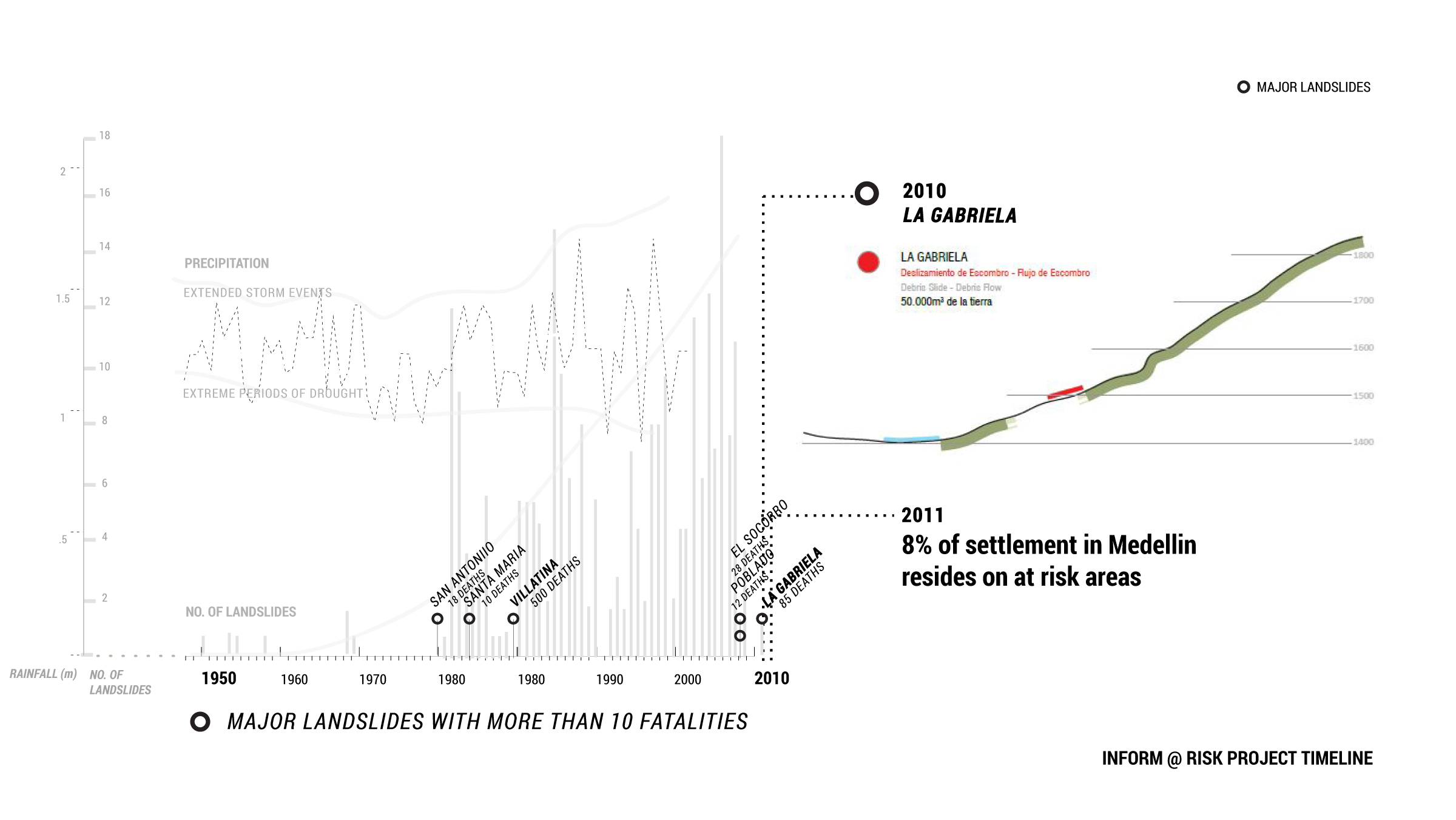

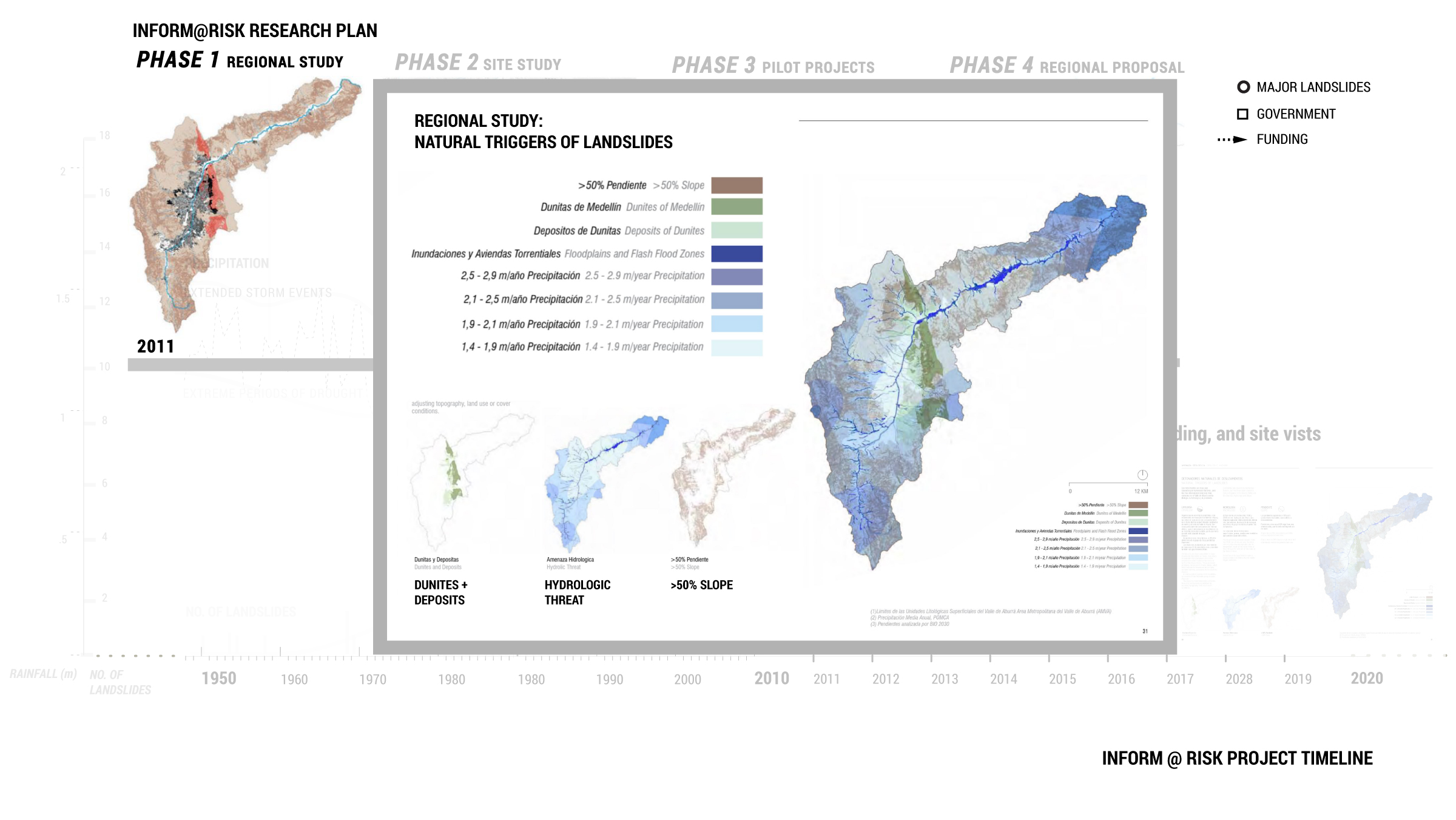

The city of Medellín sits on the banks of the Medellín River in the Aburrá Valley in Colombia’s northwest Antioquia province. Medellín is organized into 271 barrios (neighborhoods) that spread outward and up the surrounding mountains. During periods of heavy rainfall, the mountain slopes at the city’s periphery are subject to significant landslides due to the instability of their volcanic soils. These precarious lands are from barred sanctioned property development but have become home to informal settlements for residents unable to afford to live in safer areas of the city. These communities, already at risk due to their socio-economic status and a lack of functional infrastructure and government investment, thus find themselves at even greater risk. The unstable grounds on which they live, with heavier and more frequent precipitation introduced by climate change, will only become more dangerous as time passes.

Inform@Risk is a research and design initiative to study this shifting landscape and propose design interventions to support these at-risk communities. It was founded in 2010, by faculty from the Harvard Graduate School of Design and Universidad EAFIT in Medellín after one of the region’s most deadly landslides. That early research project has since evolved into an international effort by landscape architects, urban designers, community organizers, scientists, government officials, and residents. The initiative brings this range of constituents together to plan, implement, and test proposals to avoid the worst outcomes of landslides on Medellín's populated foothills. To date, Inform@Risk has initiated five pilot projects:

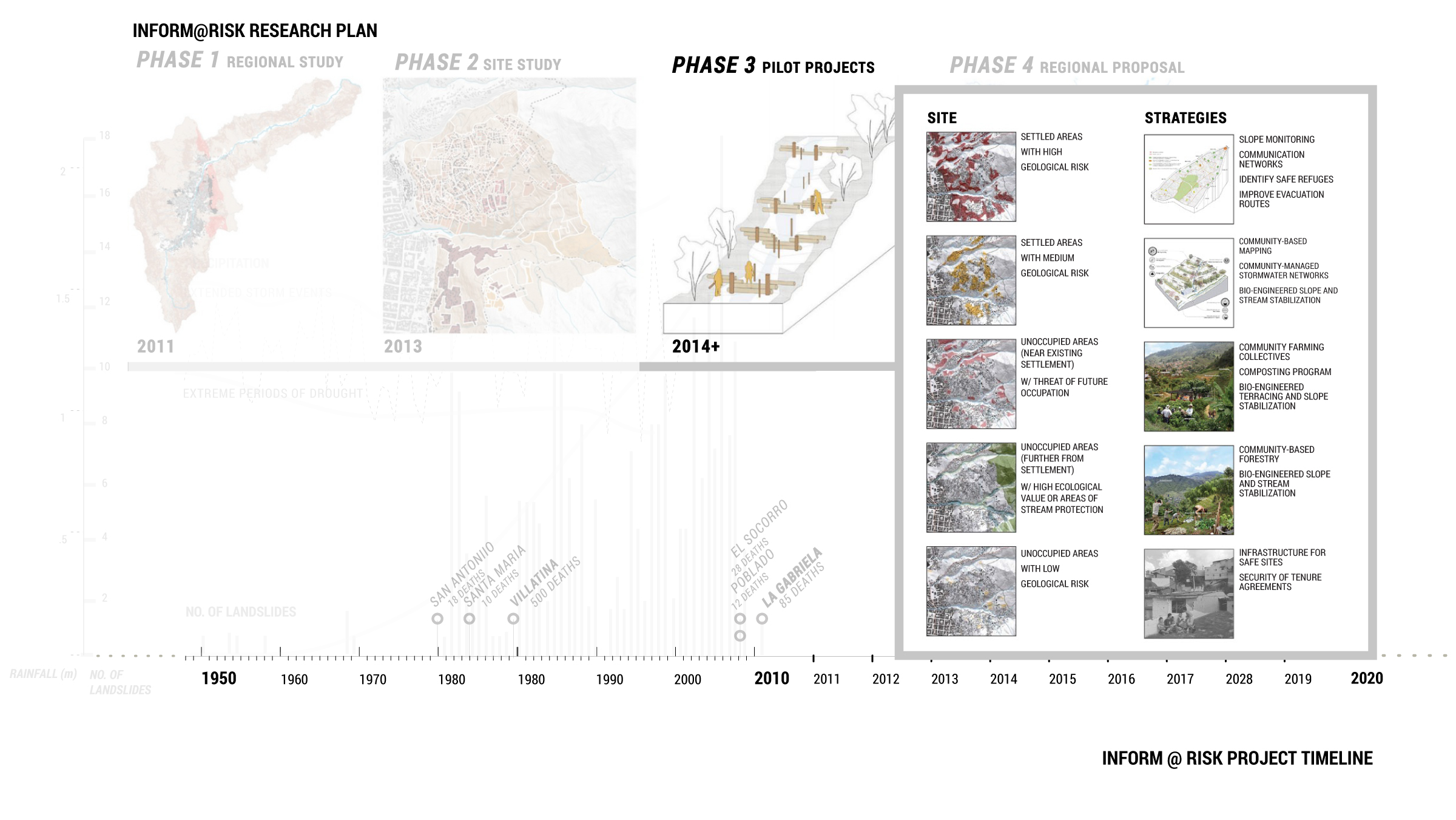

> Building evacuation routes and an early warning/alert system

> Improving soil drainage to avoid saturation

> Supporting micro-farming on steep slopes to reduce erosion

> Reestablishing protective forests

> Identifying land for future settlement growth

Across the pilot projects, Inform@Risk employs an approach that embraces on-the-ground political and economic realities. It does so by proposing an array of phased, tactical solutions that address systemic issues. Their work may serve as a model for how landscape architects can address complex climate challenges in socially, economically, and politically vulnerable contexts while also highlighting the limitations of the profession and overarching issues of environmental inequity.

Inform@Risk is a research and design initiative to study this shifting landscape and propose design interventions to support these at-risk communities. It was founded in 2010, by faculty from the Harvard Graduate School of Design and Universidad EAFIT in Medellín after one of the region’s most deadly landslides. That early research project has since evolved into an international effort by landscape architects, urban designers, community organizers, scientists, government officials, and residents. The initiative brings this range of constituents together to plan, implement, and test proposals to avoid the worst outcomes of landslides on Medellín's populated foothills. To date, Inform@Risk has initiated five pilot projects:

> Building evacuation routes and an early warning/alert system

> Improving soil drainage to avoid saturation

> Supporting micro-farming on steep slopes to reduce erosion

> Reestablishing protective forests

> Identifying land for future settlement growth

Across the pilot projects, Inform@Risk employs an approach that embraces on-the-ground political and economic realities. It does so by proposing an array of phased, tactical solutions that address systemic issues. Their work may serve as a model for how landscape architects can address complex climate challenges in socially, economically, and politically vulnerable contexts while also highlighting the limitations of the profession and overarching issues of environmental inequity.

Organizations & Collaborators

Geographers

- German Aerospace Center: Remote Sensing (DLR)

- Technical University Deggendorf: Geoinformatics (THD)

- Office for Aerial Photo Analysis and Environmental Issues (SLU)

Risk Management

- Sistema de Alerta Temprana del valle de Aburrá: Regional Warning Agency, Medellín (SIATA)

- Departamento Administrativo de Gestión del Riesgo de Desastres: Disaster Management (DAGRD)

- Multipliers: Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible (MADS)

Engineers

- AlpGeorisk: Early Warning Systems (AGR)

- Technical University of Munich: Engineering Geology (TUM)

- Sociedad Colombiana de Geología (SCG)

- German Aerospace Center: Remote Sensing (DLR)

- Technical University Deggendorf: Geoinformatics (THD)

- Office for Aerial Photo Analysis and Environmental Issues (SLU)

Risk Management

- Sistema de Alerta Temprana del valle de Aburrá: Regional Warning Agency, Medellín (SIATA)

- Departamento Administrativo de Gestión del Riesgo de Desastres: Disaster Management (DAGRD)

- Multipliers: Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible (MADS)

Engineers

- AlpGeorisk: Early Warning Systems (AGR)

- Technical University of Munich: Engineering Geology (TUM)

- Sociedad Colombiana de Geología (SCG)

Community

- Defensa Civil: Civil Based risk management (DC)

- Fundaçion Sumapaz: Community management (FS)

- Oficina de Resiliencia de Medellín (ORM)

Planners

- Departamento Administrativo de Planeación: Municipal Planning Agency (DAP)

- urbam: Centro de Estudios Urbanos y Ambientales: planning (EAFIT)

- Leibniz Universität Hannover Institute of Landscape Architecture (LUH)

- Defensa Civil: Civil Based risk management (DC)

- Fundaçion Sumapaz: Community management (FS)

- Oficina de Resiliencia de Medellín (ORM)

Planners

- Departamento Administrativo de Planeación: Municipal Planning Agency (DAP)

- urbam: Centro de Estudios Urbanos y Ambientales: planning (EAFIT)

- Leibniz Universität Hannover Institute of Landscape Architecture (LUH)

Key Terms

hazard reduction - risk reduction - scenario planning - training program - evacuation plan - environmental justice - displacement - post-conflict - geosensors - informal settlements - erosion - deforestation - landslide - community engagement - disaster risk-management - non-formal urbanization - quebradas (ravines)

SETTLEMENT AND RISK

RAIN AND RISK

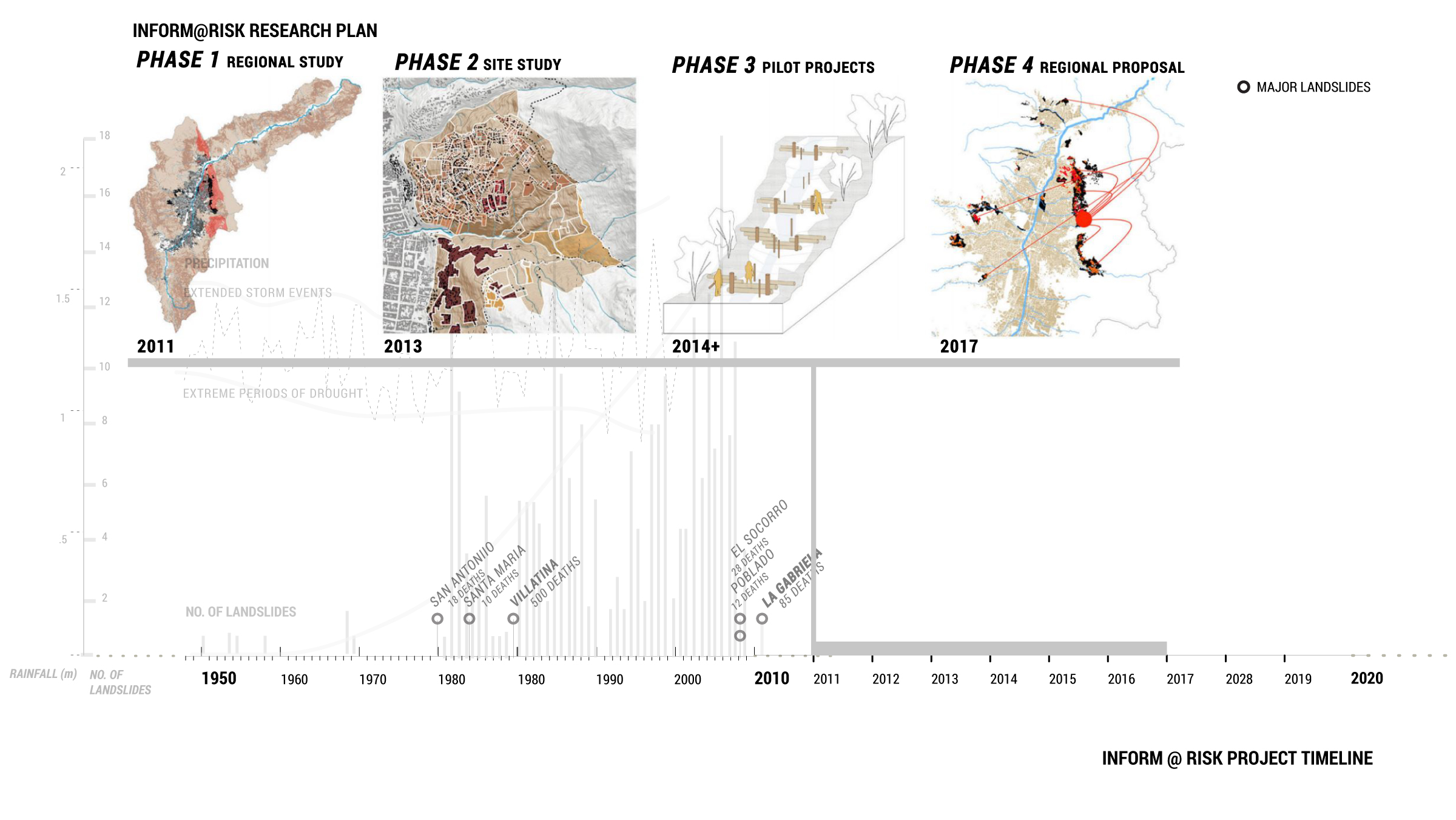

INFORM@RISK PROCESS

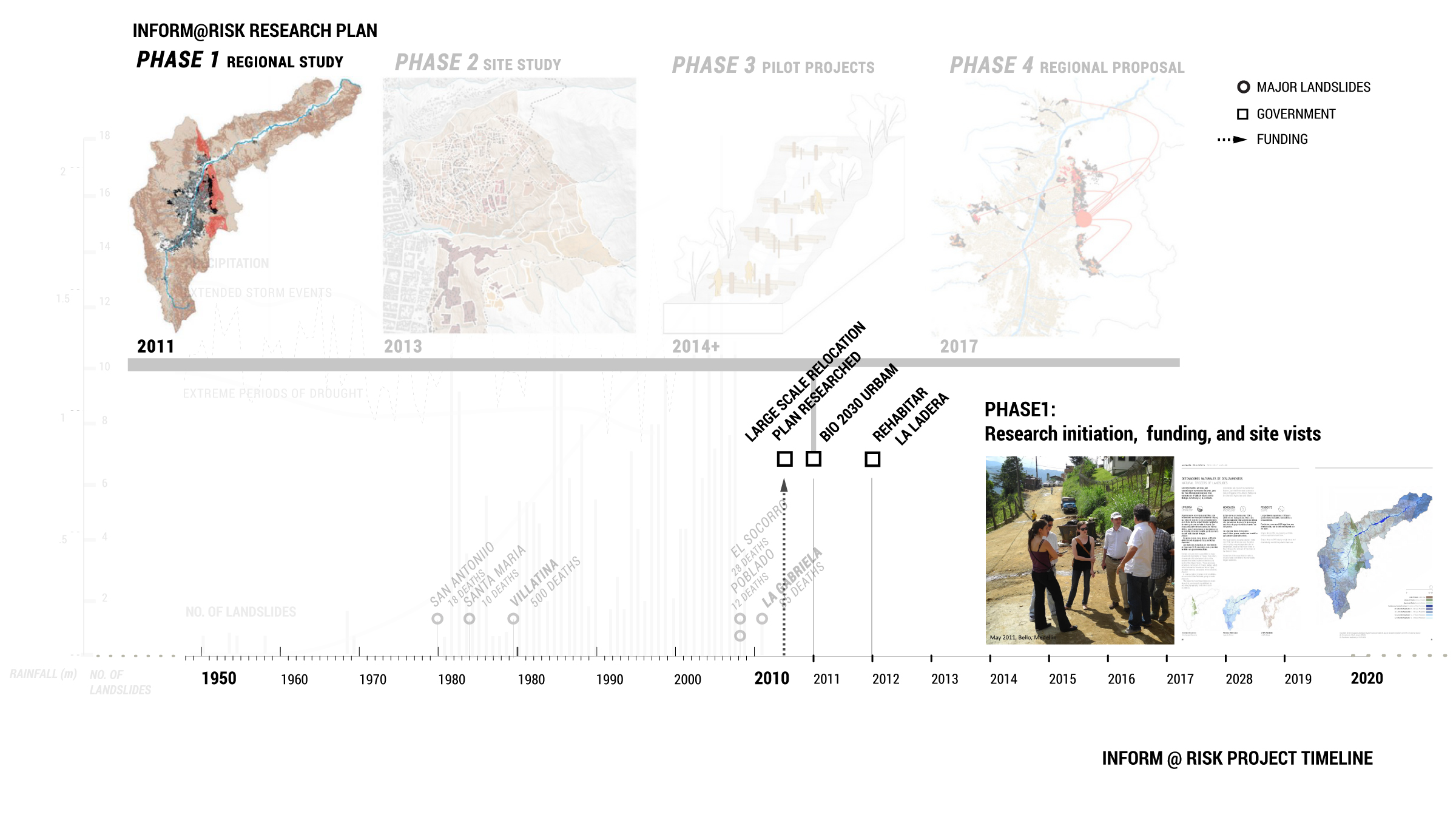

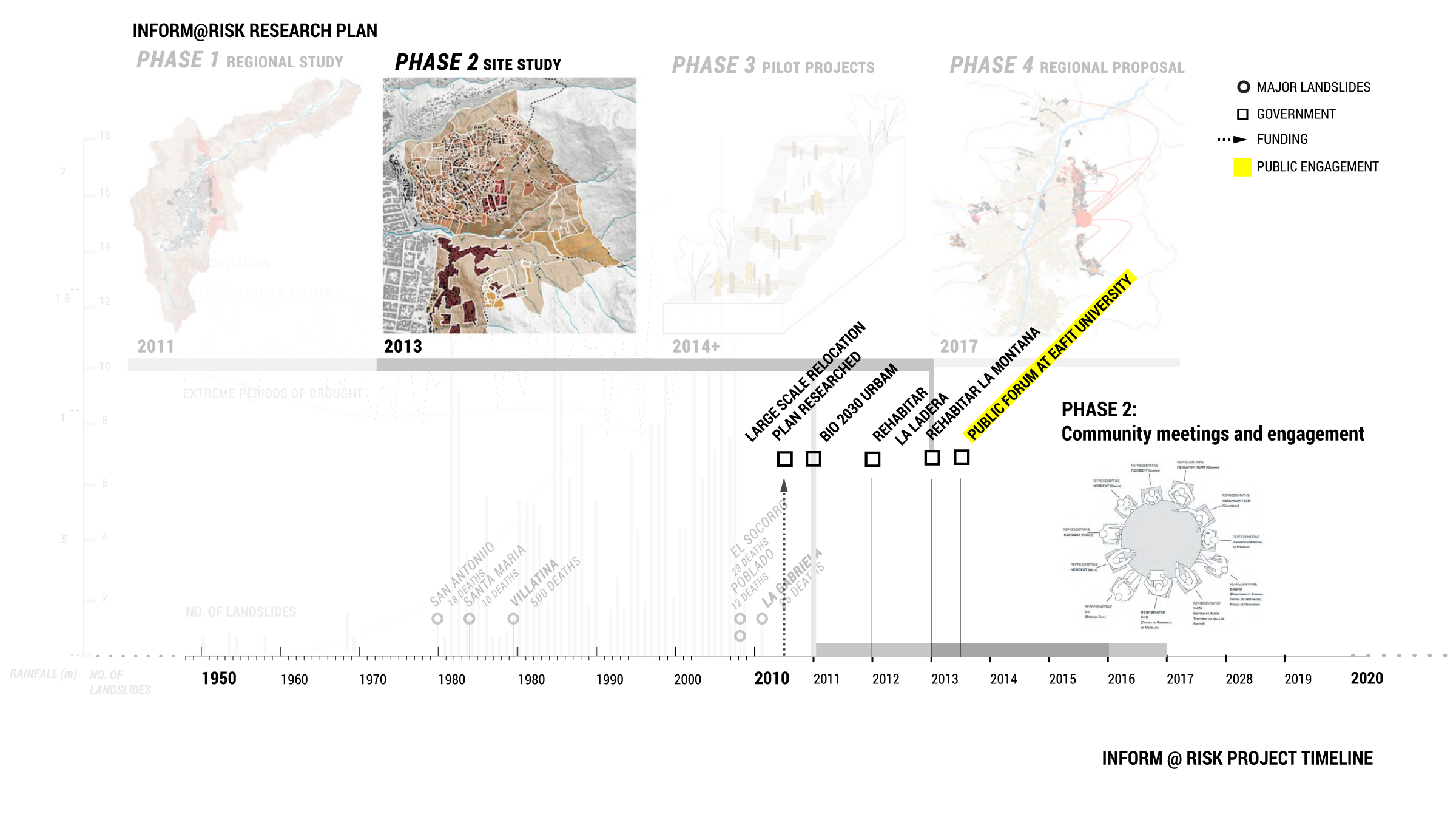

Phase One

· Project initiation

· Work supported by the primary researchers’ academic institutions (EAFIT and GSD)

· Mapped the conditions of risk at the urban scale

· Findings published in the group’s first report, Shifting Ground: Precarious Settlements and Geological Hazard in Medellín, in 2012

Phase Two

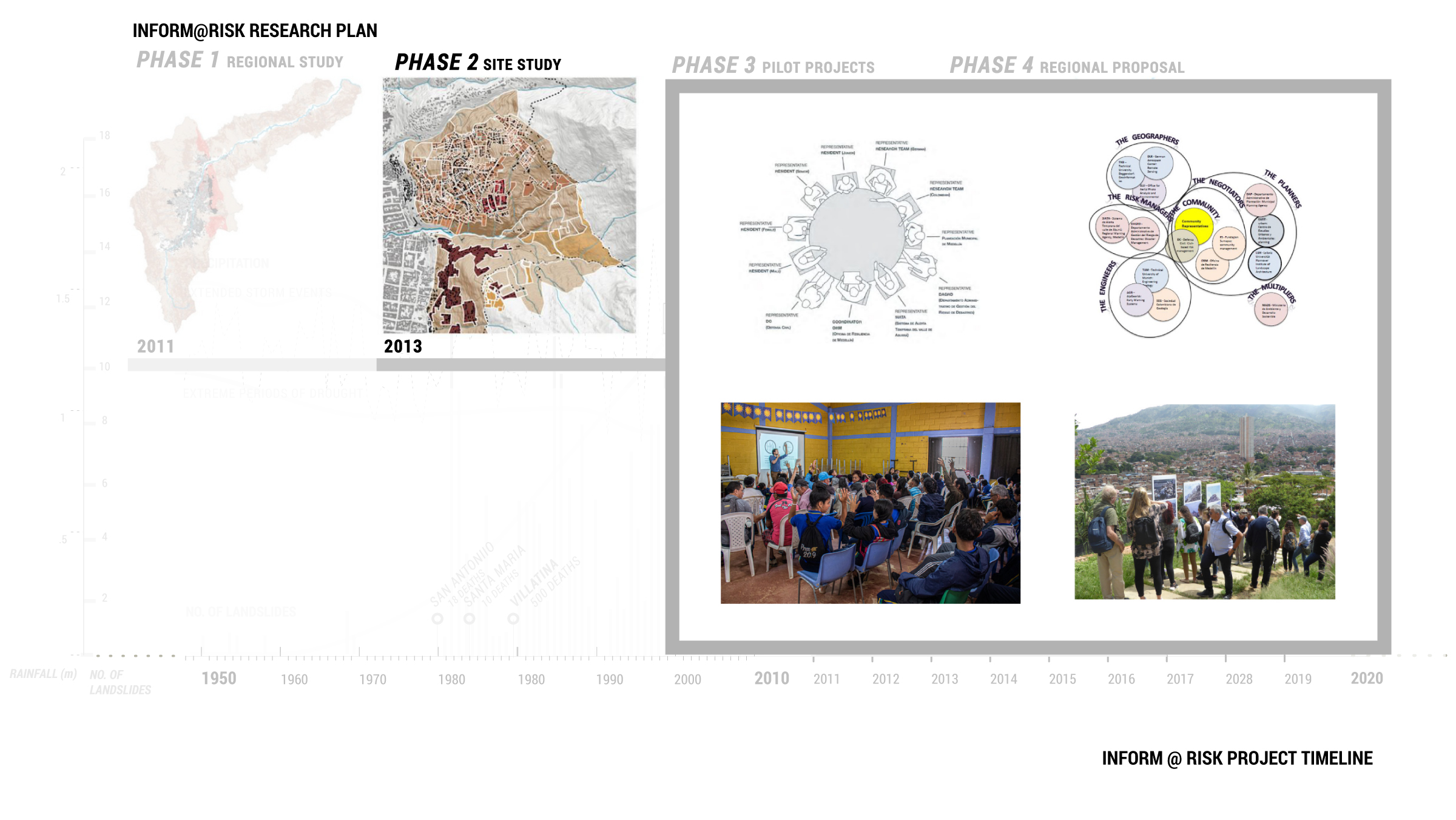

· Two neighborhoods – La Honda and La Cruz – selected by Inform@Risk for closer assessment as potential pilot project sites.

· Outside researchers went to Medellín on several site visits

· Local researchers conducted many community meetings and engagement sessions

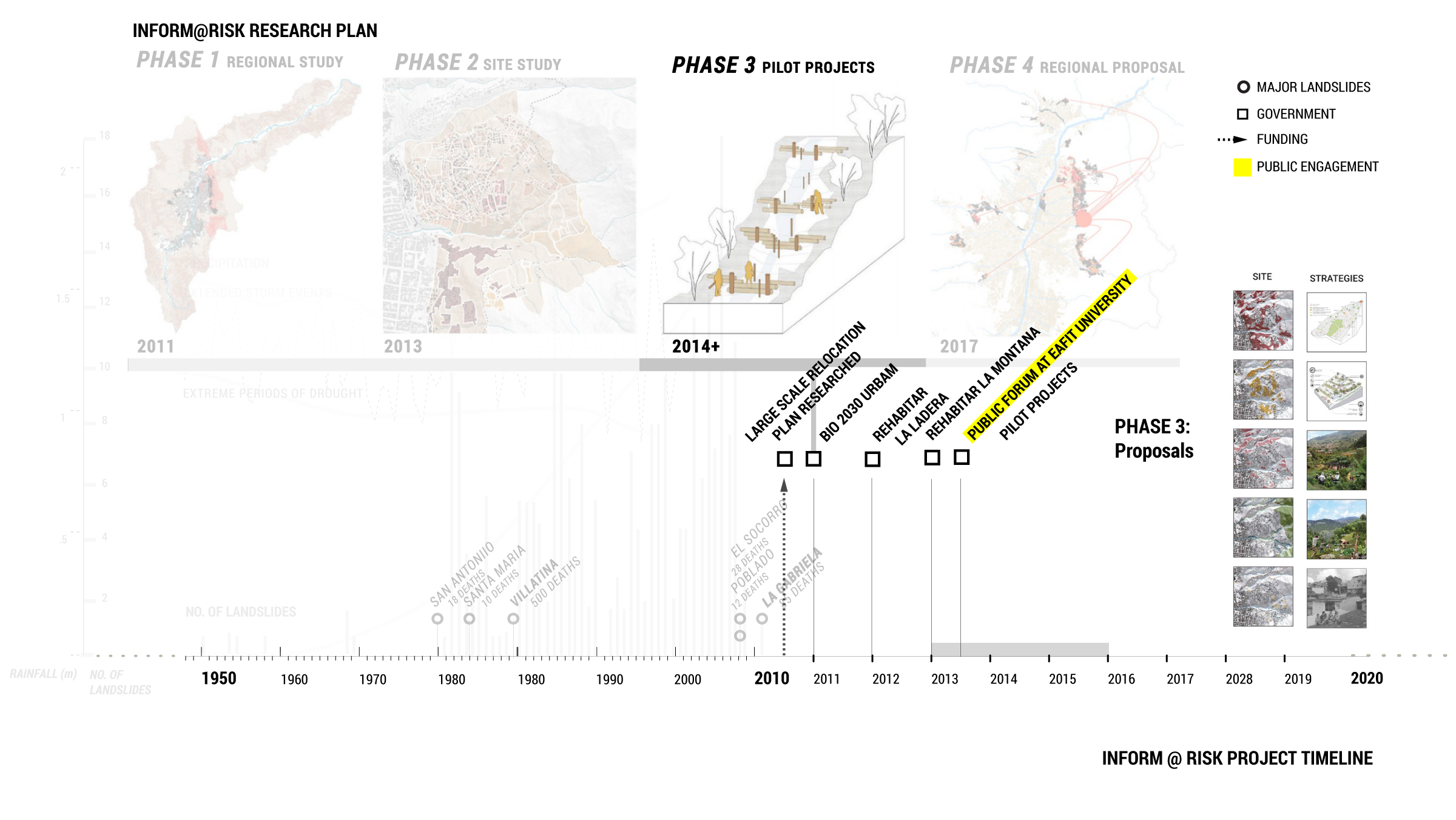

Phase Three

· Five pilot projects designed to be implemented on sites within La Honda and La Cruz proposed based on the team’s research

· Phased implementation (short, medium, and long-term) and assessment of these projects

· Proposals for the five pilot projects were published in two articles:

o Rehabitar la Montaña: Strategies and Processes for Sustainable Communities in the Mountainous Periphery of Medellín (Claghorn, et al., 2015)

o Shifting Ground: Landslide Risk Mitigation through Community-based Landscape Interventions (Claghorn and Werthmann, 2015)

· This is the current stage of the project, with particular emphasis placed on the development and installation of an early warning system and improved evacuation infrastructure. Specific sites have yet to be selected for the remaining four pilot project concepts.

· Community outreach work adapted to conform to COVID-19 measures (quarantine, social distancing, etc.)

Phase Four (forthcoming)

Development and presentation of a regional plan based on pilot project initial findings.

While this design model altogether – researchers from elite foreign universities coming into Medellín to “problem solve” – is open for critique, Inform@Risk’s work represents a decade-long engagement (certain to continue for several more years) that includes many Medellín based participants. Throughout each phase the team’s work has been marked by collaboration, community, and communication. It reveals how landscape architects are well-positioned to convene, coordinate, and facilitate the work of complex interdisciplinary teams across scales while ensuring that ownership remains with residents.

DESIGN PROPOSALS

QUESTIONS

What design and non-design roles can landscape architects play in addressing complex climate-based challenges? What are the limits of our expertise and in what ways could our field expand in new directions?

How can we design a long-term, multi-phase project that remains responsive to imminent needs?

Inform@Risk attempts to ensure that its proposals are attainable for communities with limited resources. Accepting these conditions is pragmatic, but by working within these constraints rather than challenging the inequities that produce them, does Inform@Risk ultimately reproduce and re-affirm an unjust status quo? If so, how could Inform@Risk operate differently? Is it possible to challenge structural inequity while still providing urgent support to at-risk communities?

How can we design a long-term, multi-phase project that remains responsive to imminent needs?

Inform@Risk attempts to ensure that its proposals are attainable for communities with limited resources. Accepting these conditions is pragmatic, but by working within these constraints rather than challenging the inequities that produce them, does Inform@Risk ultimately reproduce and re-affirm an unjust status quo? If so, how could Inform@Risk operate differently? Is it possible to challenge structural inequity while still providing urgent support to at-risk communities?

SOURCES

Alberti, Stefano, Giovanni Battista Crosta, Gonghui Wang, Giuseppe Dattola, and Davide Bertolo. “Influence of Graphite and Serpentine Materials along Landslide Failure Surfaces.” Geophysical Research Abstracts 19 (2017). https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2017EGUGA..19.8653A/abstract.

Betancur, John J. “Approaches to the Regularization of Informal Settlements: The Case of PRIMED in Medellín, Colombia.” Global Urban Development Magazine 3, 1 (November 2007). https://www.globalurban.org/GUDMag07Vol3Iss1/Betancur.htm.

California Department of Conservation. “Serpentine: California’s State Rock.“ https://www.conservation.ca.gov/cgs/Pages/Publications/Note_14.aspx

Chopra, P. N., and M. S. Paterson. “The Role of Water in the Deformation of Dunite.” Solid Earth: Journal of Geophysical Research 89, B9 (10 September 1984): 7861-76. https://doi.org/10.1029/JB089iB09p07861.

Claghorn, Joseph, Francesco Maria Orsini, Carlos Alejandro Echeverri Restrepo, and Christian Werthmann. "Rehabitar la Montaña: Strategies and Processes for Sustainable Communities in the Mountainous Periphery of Medellín." Urbe Revista Brasileira de Gestão Urbana (Brazilian Journal of Urban Management) (January 2015). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287111064_Rehabitar_la_Montana_Strategies_and_processes_for_sustainable_communities_in_the_mountainous_periphery_of_Medellin.

Claghorn, Joseph, and Christian Werthmann. "Shifting Ground: Landslide Risk Mitigation through Community-based Landscape Interventions." Journal of Landscape Architecture 10, no. 1 (2015): 6-15.

Echeverri, Alejandro, Ana Elvira Vélez, and Christian Werthmann (eds.). Shifting Ground: Precarious Settlements and Geological Hazard in Medellín. Medellín: Universidad EAFIT and Harvard Graduate School of Design, 2012.

Finn, Megan. “Making Sense of Earthquakes: Public Information Infrastructures and Postdisaster Event Epistemologies.” In Documenting Aftermath: Information Infrastructures in the Wake of Disasters. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2018: 1-18.

Schnitter Castellanos, Patricia. “Wiener and Sert’s Pilot Plan for Medellín. Contract and Presentation. Colombian Urban Planning and its Vicissitudes.” Paper presented at the 11th Conference of the International Planning History Society, Barcelona, Spain, July 14-17, 2004. http://www-etsav.upc.es/personals/iphs2004/pdf/194_p.pdf.

Werthmann, Christian. “Inform@Risk.” ResearchGate Project Page. Accessed July 6, 2020. https://www.researchgate.net/project/InformRisk.

Werthmann, Christian. "Inform@Risk: Improving the Resilience of Informal Urbanization against Landslides through Participative Networks of Early Warning Systems, Web-based Technologies, and Landscape Design." 2019.