POST-SANDY NY

Overview

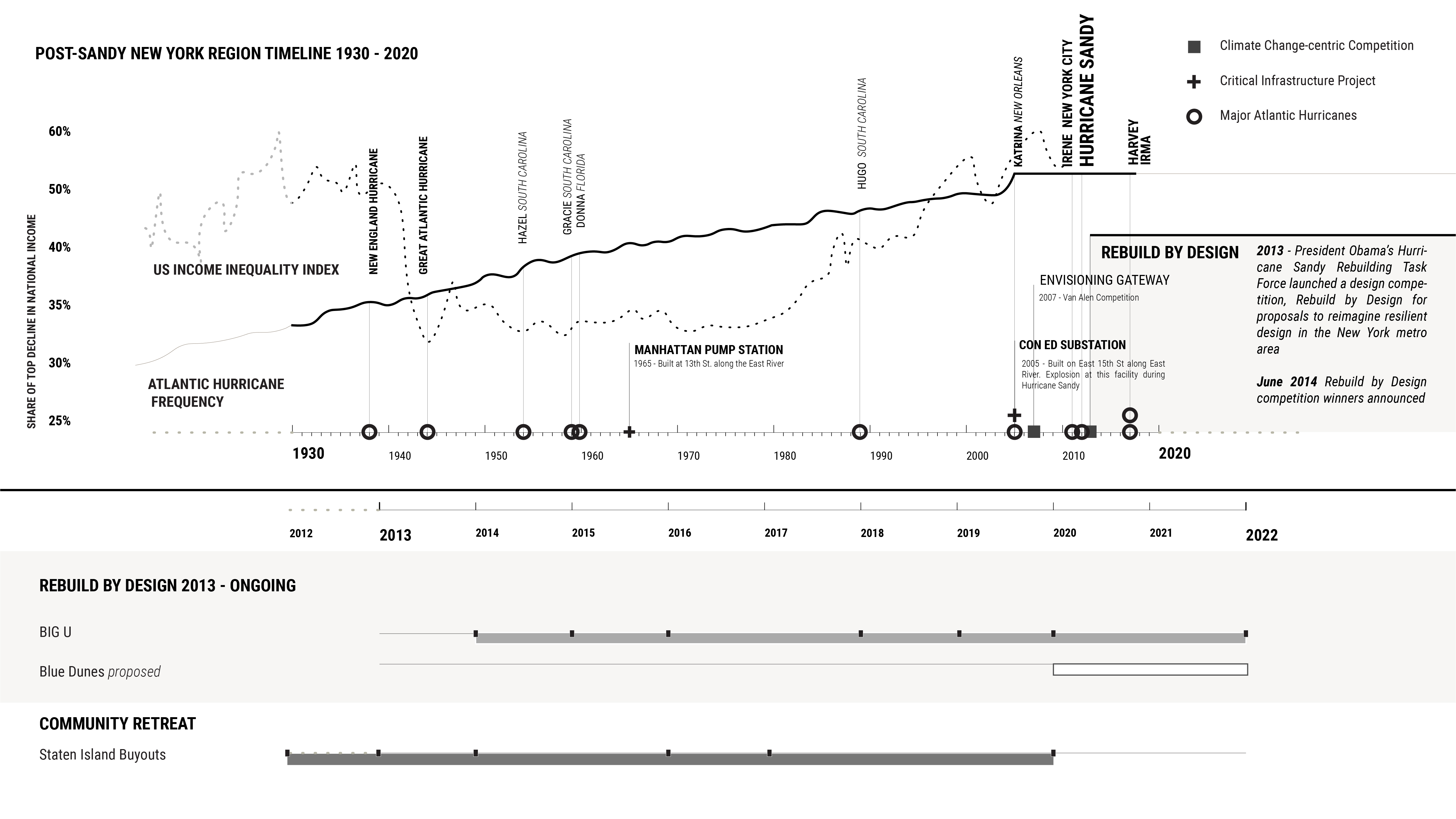

Hurricane Sandy made landfall on the New Jersey shore on October 29th, 2012 and caused unprecedented damage throughout the New York metro area. Storm surges, heavy rain, and high winds led to flooding in Lower Manhattan, decimated homes in eastern Staten Island and coastal Queens, and killed more than 100 people throughout the tri-state area. Although the storm was particularly fierce, its destruction was amplified by long-standing issues related to the region’s lack of adequate safe, affordable housing, ongoing displacement of underprivileged communities to geographically vulnerable areas, insufficient emergency services, and repeated disregard for the dangers of coastal development.

Instead of addressing the structural social inequities that exacerbated the damage wrought by Hurricane Sandy, the federal government -- using the Netherlands as its guide -- decided to embrace flood prevention projects meant to embody a depoliticized notion of “resilience” and environmentally savvy design. In 2013, one year after the storm, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) launched “Rebuild by Design,” a competition open to scientists, architects, engineers, academics, and other experts to propose climate mitigation projects ranging from large infrastructure projects to small scale residential retrofits. The proposed projects were sited in flood vulnerable areas across the New York Region, with seven different projects ultimately chosen by the committee to plan and build. Many proposals included input from landscape architecture firms, and while the competition may have raised landscape architecture’s public profile, the competition also raised questions about the discipline’s role in enabling this form of resilience planning which favors depoliticized technocratic fixes over addressing structural problems. Some critics question whether by emphasizing “state-of-the-art” and ambitious design, a competition that might have focused on the needs of vulnerable communities had instead become a bidding contest for famous international firms (Depuis et al. 2019).

This dossier examines three different proposals for post-Sandy design:

- The Big U

- Blue Dunes

- Staten Island Buyouts (NY Rising Enhanced Buyout Program)

Both the Big U and Blue Dunes projects were entries in the Rebuild by Design competition. The BIG U, a winning proposal submitted by the Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) and various collaborators, is a combination of sea-walls and berms designed to protect Lower Manhattan from flooding. Blue Dunes, designed by West 8 and WXY Architecture, proposed a chain of barrier islands built from dredge material that would serve as living storm buffers for the entire New York harbor. The Blue Dunes project was not ultimately selected by the competition jurors as a winning proposal, though it remains a strong precedent project to study for future climate designs. In contrast to the previous two projects, the Staten Island Buyouts program was not part of the Rebuild by Design competition, and was instead organized first by community members and later funded under the state’s NY Rising program. The program allowed homeowners in select communities on Staten Island‘s eastern shore to sell their homes to the state to be converted into wetlands into perpetuity.

Although the Rebuild by Design projects and the Staten Island Buyouts are not complete, it is already clear from the processes that have unfolded to date that enormous amounts of capital cannot simply solve or save a city from future and existing threats. Though the three cases differ from each other in terms of physical scale, community engagement, budget, and design philosophy, none provides a long term solution to the climate threats that NYC faces nor engages with the fact that projects conceived on short schedules, swayed by powerful lobbies, and committed to conventional engineering tactics are unlikely to provide lasting coastal resilience (Depuis et al 2019).

Many cities, towns, and counties in the United States will not receive the same large scale public funding packages - that are typically only given in the form of grants by the federal government - that the New York Region received. Even with such funds New York City remains reliant on a range of funding sources. Comparable municipalities will and are devising their own mitigation plans with an amalgam of resources they can muster from local government, the private sector, and philanthropy.

Instead of addressing the structural social inequities that exacerbated the damage wrought by Hurricane Sandy, the federal government -- using the Netherlands as its guide -- decided to embrace flood prevention projects meant to embody a depoliticized notion of “resilience” and environmentally savvy design. In 2013, one year after the storm, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) launched “Rebuild by Design,” a competition open to scientists, architects, engineers, academics, and other experts to propose climate mitigation projects ranging from large infrastructure projects to small scale residential retrofits. The proposed projects were sited in flood vulnerable areas across the New York Region, with seven different projects ultimately chosen by the committee to plan and build. Many proposals included input from landscape architecture firms, and while the competition may have raised landscape architecture’s public profile, the competition also raised questions about the discipline’s role in enabling this form of resilience planning which favors depoliticized technocratic fixes over addressing structural problems. Some critics question whether by emphasizing “state-of-the-art” and ambitious design, a competition that might have focused on the needs of vulnerable communities had instead become a bidding contest for famous international firms (Depuis et al. 2019).

This dossier examines three different proposals for post-Sandy design:

- The Big U

- Blue Dunes

- Staten Island Buyouts (NY Rising Enhanced Buyout Program)

Both the Big U and Blue Dunes projects were entries in the Rebuild by Design competition. The BIG U, a winning proposal submitted by the Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) and various collaborators, is a combination of sea-walls and berms designed to protect Lower Manhattan from flooding. Blue Dunes, designed by West 8 and WXY Architecture, proposed a chain of barrier islands built from dredge material that would serve as living storm buffers for the entire New York harbor. The Blue Dunes project was not ultimately selected by the competition jurors as a winning proposal, though it remains a strong precedent project to study for future climate designs. In contrast to the previous two projects, the Staten Island Buyouts program was not part of the Rebuild by Design competition, and was instead organized first by community members and later funded under the state’s NY Rising program. The program allowed homeowners in select communities on Staten Island‘s eastern shore to sell their homes to the state to be converted into wetlands into perpetuity.

Although the Rebuild by Design projects and the Staten Island Buyouts are not complete, it is already clear from the processes that have unfolded to date that enormous amounts of capital cannot simply solve or save a city from future and existing threats. Though the three cases differ from each other in terms of physical scale, community engagement, budget, and design philosophy, none provides a long term solution to the climate threats that NYC faces nor engages with the fact that projects conceived on short schedules, swayed by powerful lobbies, and committed to conventional engineering tactics are unlikely to provide lasting coastal resilience (Depuis et al 2019).

Many cities, towns, and counties in the United States will not receive the same large scale public funding packages - that are typically only given in the form of grants by the federal government - that the New York Region received. Even with such funds New York City remains reliant on a range of funding sources. Comparable municipalities will and are devising their own mitigation plans with an amalgam of resources they can muster from local government, the private sector, and philanthropy.

Organizations

• Rebuild by Design

• US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)

• Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA)

• Governor’s Office of Storm Recovery

• Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency

• West 8

• WXY Architecture

• Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG)

• East River Park Action

• US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)

• Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA)

• Governor’s Office of Storm Recovery

• Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency

• West 8

• WXY Architecture

• Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG)

• East River Park Action

• Stevens Institute of Technology

• US Department of Agriculture (USDA)

• NYC Department of City Planning (NYC Planning)

• NYC Department of Parks and Recreation (NYC Parks)

• NYC Department of Transportation (DOT) • NYC Department of Design and Construction (DDC)

• US Department of Agriculture (USDA)

• NYC Department of City Planning (NYC Planning)

• NYC Department of Parks and Recreation (NYC Parks)

• NYC Department of Transportation (DOT) • NYC Department of Design and Construction (DDC)

Key Terms

resilience - adaptation - managed retreat - storm surge - National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) - berm - barrier island - dune - wave attenuation - rewilding - uniform land use review process (ULURP) - green growth machine - gentrification - critical infrastructure - buyout - fair market value (FMW) - cost-benefit analysis (CBA) - tidal flooding - coastal flooding - 100 year flood

Coastal Lands

An estimated one in ten people in the world live in a low-elevation coastal zone. Nearly all major coastal cities are at major risk from rising sea levels due to climate change. As of 2014, nearly 400,000 people and counting live in New York City’s 1% risk floodplain. By 2050, the floodplain is projected to expand to encompass an area, across all NYC boroughs, that is 1.5 times the size of Manhattan island (NYC Office of Emergency Management 2014). The City’s densely populated flood zone is not unique; other cities such as Miami, Kolkata, and Guangzhou have similar conditions and their coastal locations make them vulnerable to the kind of destruction that NYC experienced during Hurricane Sandy.

HURRICANE SANDY

Hurricane Sandy

Warming water temperature trends off the Eastern Seaboard (and globally) are proving to be engines for tropical cyclones, which are called Hurricanes in the US (Knutson et al. 2015). Warmer waters lead to more available heat energy and more moisture in the atmosphere, which increase the likelihood and intensity of storms (Holland et al. 2019). Hurricane Sandy was New York’s first reckoning with the ramifications of this ocean temperature rise, shining a light on what is to come with a changing climate where more communities along the U.S. eastern seaboard will be exposed to higher risks from coastal flooding.

CLIMATE + CONTEXT

Risk and Value

Hurricane Sandy laid bare the ways the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) policies had put coastal communities from New Jersey to Connecticut at high risk of coastal flooding. The agency's flood maps, which determine insurance rates, had not been updated since 1980 when Sandy hit the region (ProPublica 2013). Hurricane Sandy's devastation demonstrated the inadequacy of these flood and homeowners insurance maps to account for catastrophic flooding and risk to human life, and they will need to be continually updated to reflect the current rate of coastal climate change. Continuing to prioritize property values over people’s safety, federal and state strategies have authorized and embraced redevelopment initiatives in areas that remain vulnerable to flooding.

______________________________

1 The 1% risk floodplain refers to an area with a 1% risk of flooding in any given year. This is also known as the 100 year floodplain. These concepts are some of the most widely used metrics to explain flood risk but they are inherently convoluted and misleading. A 100 year flood is not a flood that occurs every 100 years but rather it is a flood that has a 1% or greater chance of occurring in a given year. A 100 year flood today, for example, (even absent future sea level rise projections) has a 26% chance of occurring over the course of a 30 year mortgage (NYC OEM 2014).

PROJECTS

Selected Cases

These three (3) cases focus on design responses in the wake of Hurricane Sandy in 2012. The Big U and Blue Dunes came out of the Rebuild by Design competition, funded by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) to specifically channel funds to areas impacted by Hurricane Sandy. The proposals that emerged were produced by multidisciplinary partnerships often led by landscape architecture firms. The projects submitted to and selected by the Rebuild By Design program set precedents for coastal resilience and yet, questions about the selection criteria for certain sites and the rejection of unconventional but perhaps farther-reaching proposals remain. For instance:

- What were the prevailing conditions in NYC that made Hurricane Sandy so destructive in some areas and less so in others?

- Which residents and areas were neglected for climate oriented infrastructure and other services in the years before the storm and have their vulnerabilities been adequately addressed by Rebuild by Design-funded projects?

- Who is this so-called climate infrastructure benefitting?

- Upon completion of the funded Rebuild by Design projects, which areas and communities are projected to be among the most protected from a Sandy-strength storm? And which areas and communities will be least protected?

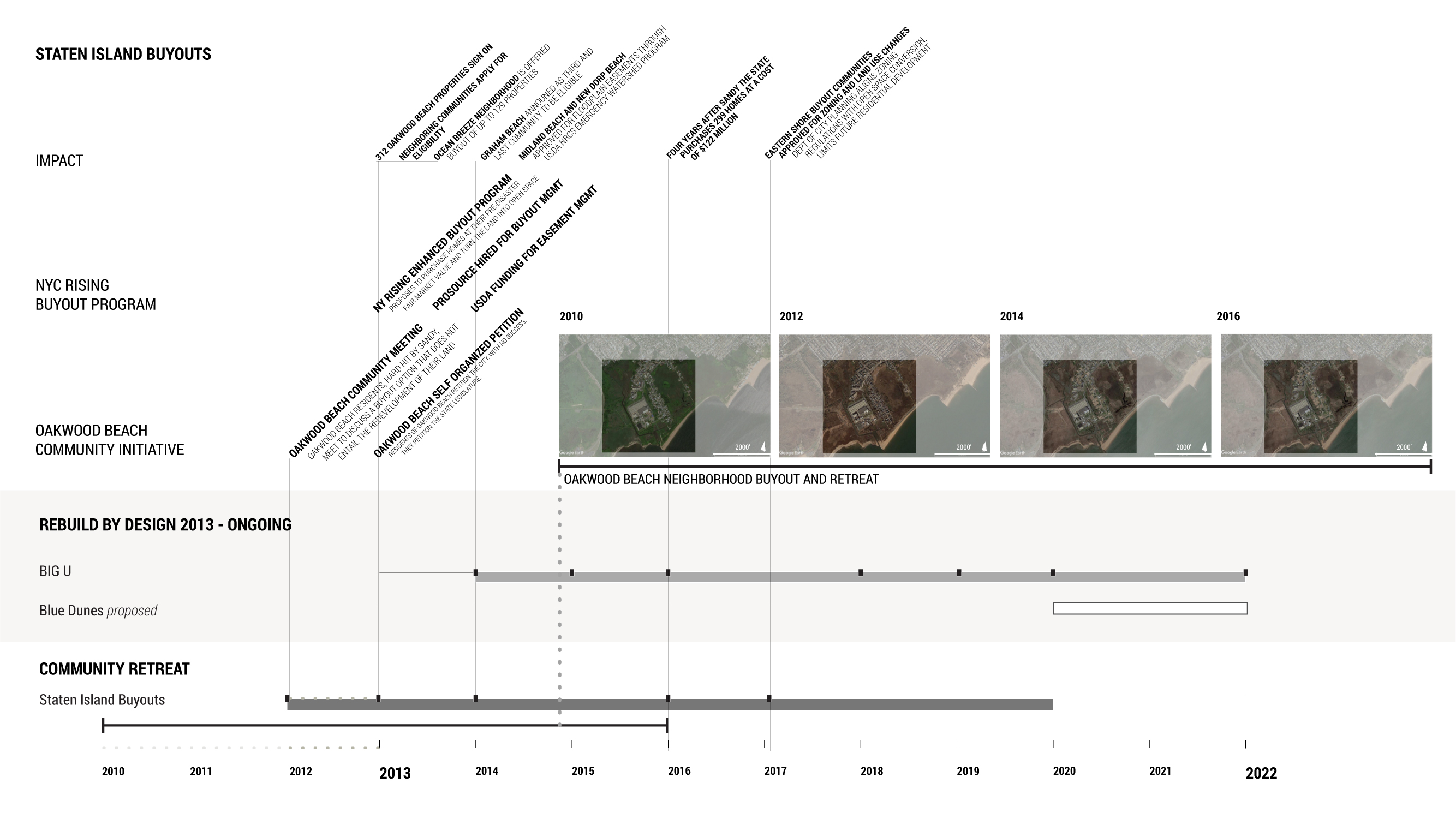

Staten Island Buyouts (NY Rising Enhanced Buyout Program)

Starting in 2012 New York State purchased properties in the Oakwood Beach, Graham Beach, and Ocean Breeze neighborhoods of Staten Island. As of 2020, and with funding provided by HUD’s Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery Program, New York State has acquired over 299 properties at a cost of 255 million dollars. Situated at the southern coast of Staten Island, these communities were among those hit hardest by a 16 foot storm surge that claimed 53 lives across the borough during Hurricane Sandy.

The Staten Island Buyout program is a managed retreat from flood prone areas along the Eastern shore of the island. Residents are paid the pre-disaster fair market value for their homes which are then demolished and the land is transitioned to wetlands, in perpetuity. This specific managed retreat process was funded and facilitated by a state run program entitled the NY Rising Enhanced Buyout Program. The program reduces the vulnerability of the community to future disasters by funding their departure from these hazard zones as well as converting the properties to marshlands which will absorb water to reduce risk in uphill communities.This process was later codified into zoning law in certain high risk flood zones.

The Staten Island Buyout Program poses questions of equity and effective risk mitigation. Homeowners must first get approved through the Governor’s Office’s NY Rising Program to have their properties purchased -- a process that requires administrative and other resources not possessed equally by all residents eligible for the program. Additionally, many of those who have accepted buyouts have resettled a mere five miles from their former homes, raising questions about whether the area designated for such a managed retreat is large enough to sufficiently reduce risks to Staten Island’s coastal populations.

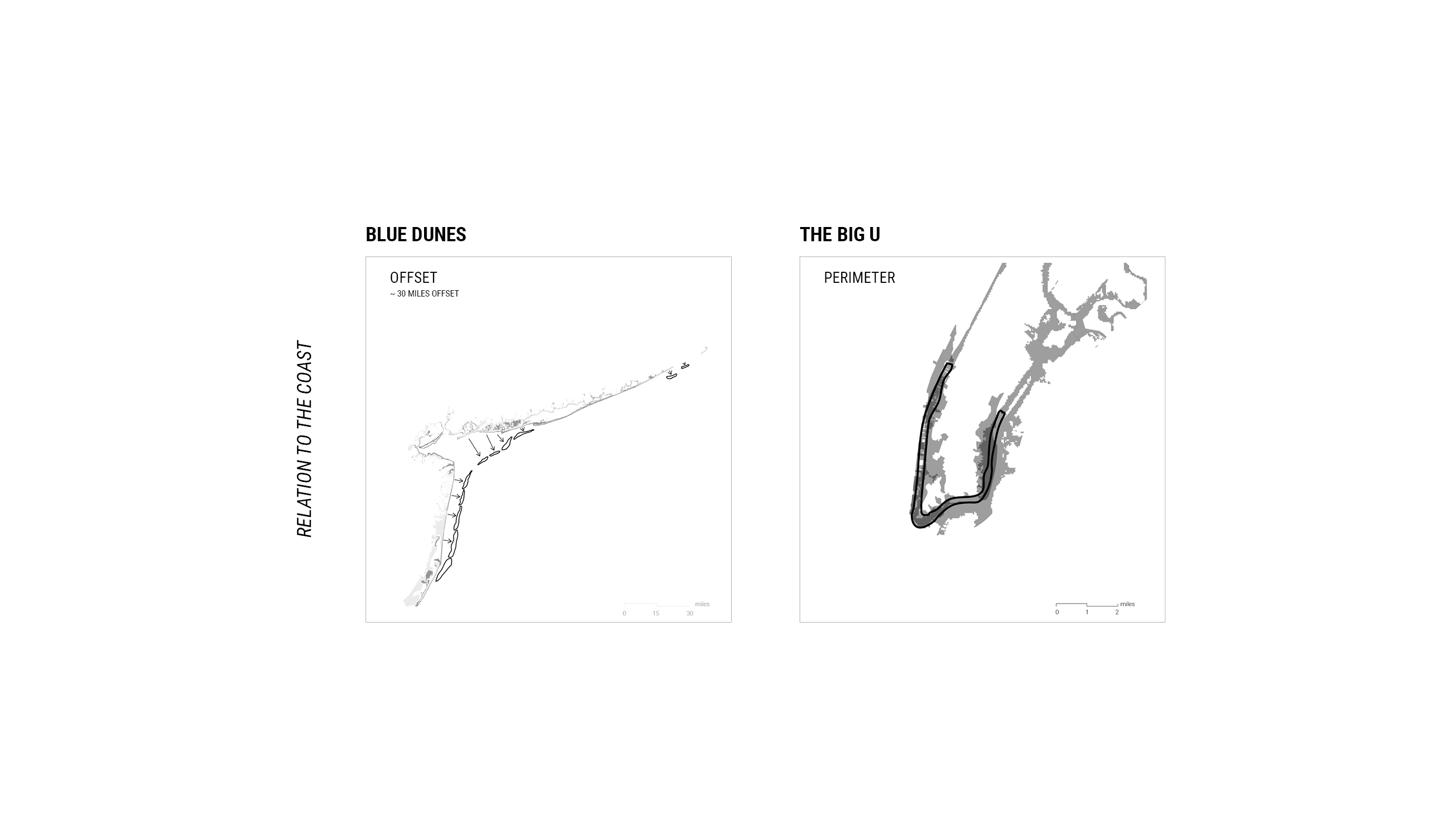

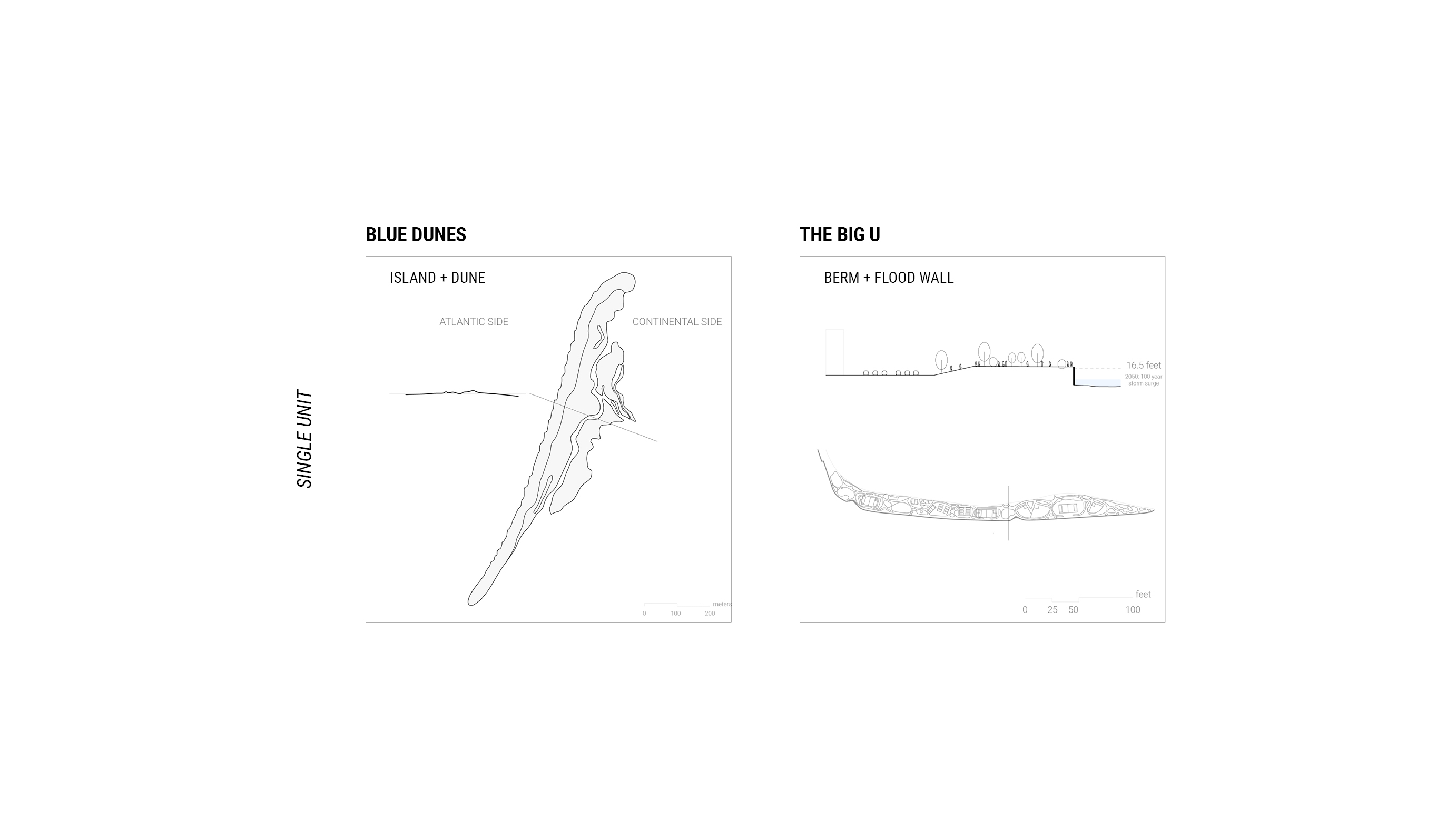

The BIG U

The BIG U is one of the seven project proposals selected by the Rebuild by Design competition for implementation and construction. The concept hinges on building 10 miles of continuous coastal barriers stretching from West 57th Street, down around lower Manhattan, and up to East 42nd Street. Construction of the project has been split into two phases: the East Side Coastal Resiliency phase and the Lower Manhattan Coastal Resiliency Project phase.

During the competition, when the Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) was still crafting its proposal for the East Side Coastal Resiliency part of the project, they sought design input from local residents in the communities projected to be affected by the building of the Big U. Since 2014, however, after HUD awarded NYC $300 million to kickstart the planning and design of the project, BIG was pressured by the city to significantly alter its proposal after value engineering proved the original design infeasible. This late in the process change left significantly less room for community collaboration (DuPuis et al. 2019). The updated proposal for the East Side Coastal Resiliency phase discarded the “Bridging Berm” -- a planted protective hill between the waterfront and the city in the existing East River Park -- and instead called for covering East River Park with landfill in order to create a sea wall 10 foot higher than the original “Bridging Berm” would have been according to the initial proposal (The Water Center 2020) . Local residents were outraged by the change in plans and felt their concerns had been ignored by both the city and BIG; residents also pointed out that the March 2020 deadline to begin construction or forfeit funding rushed the decision making process (East River Action 2020).

Blue Dunes

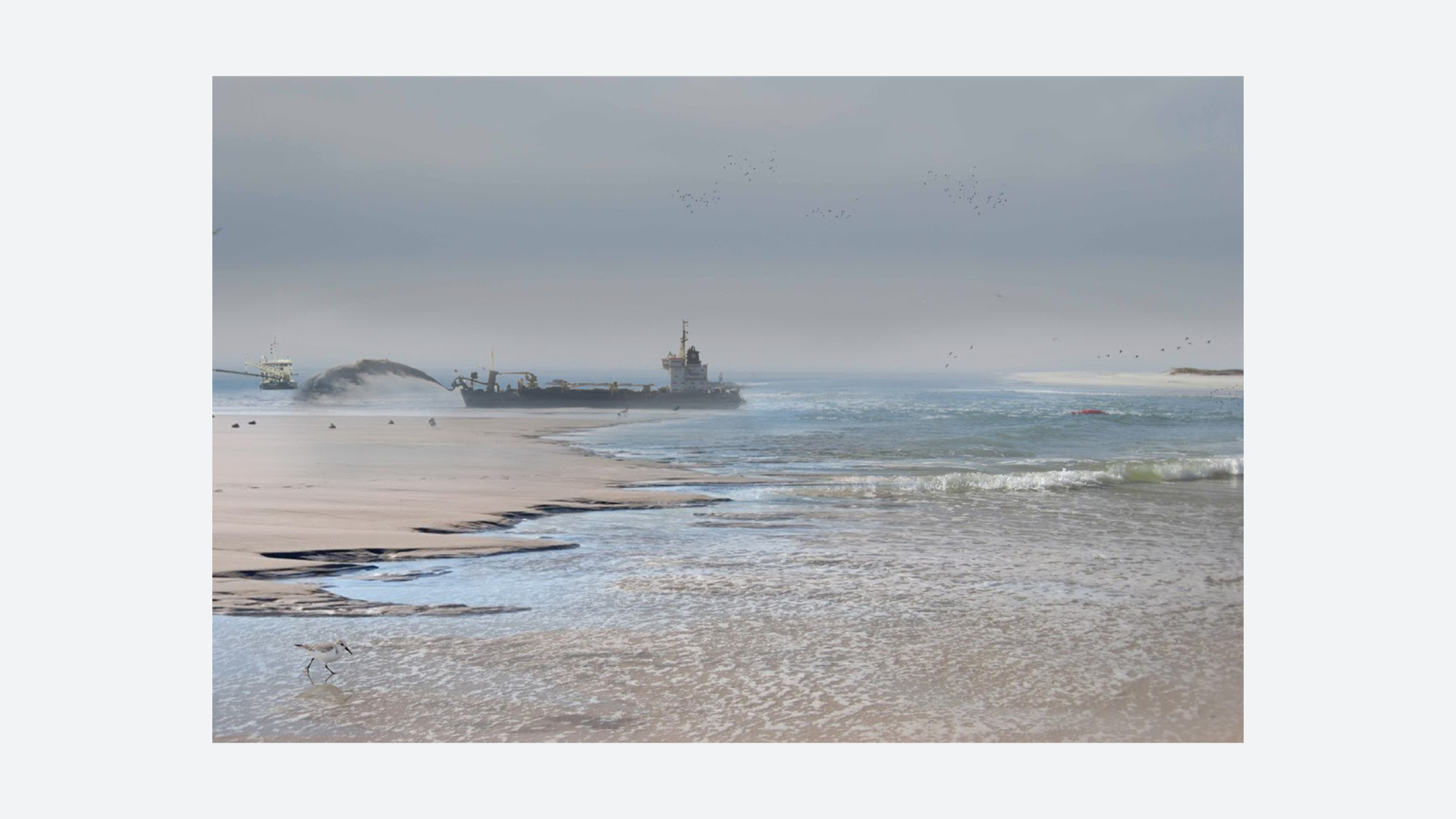

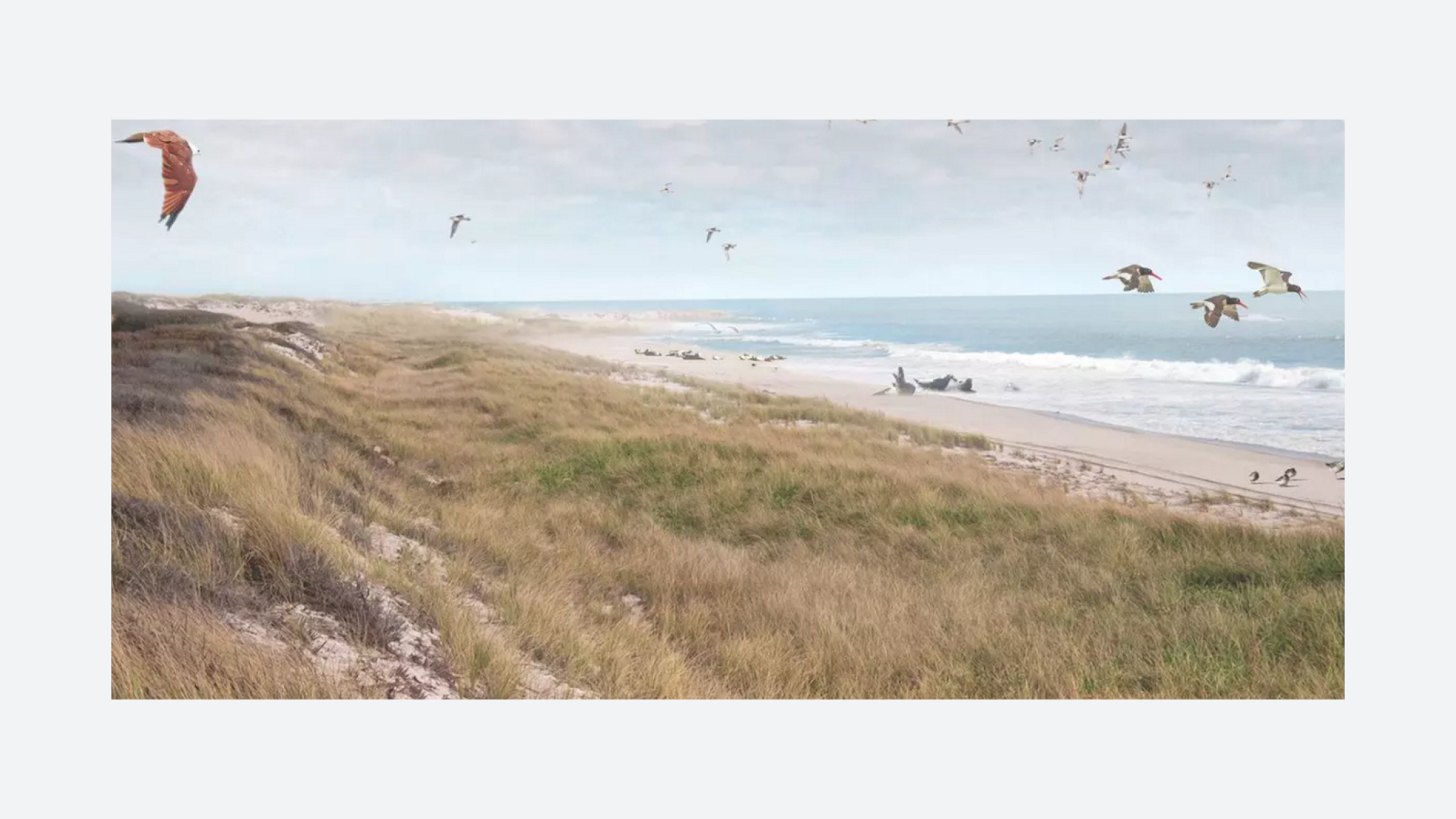

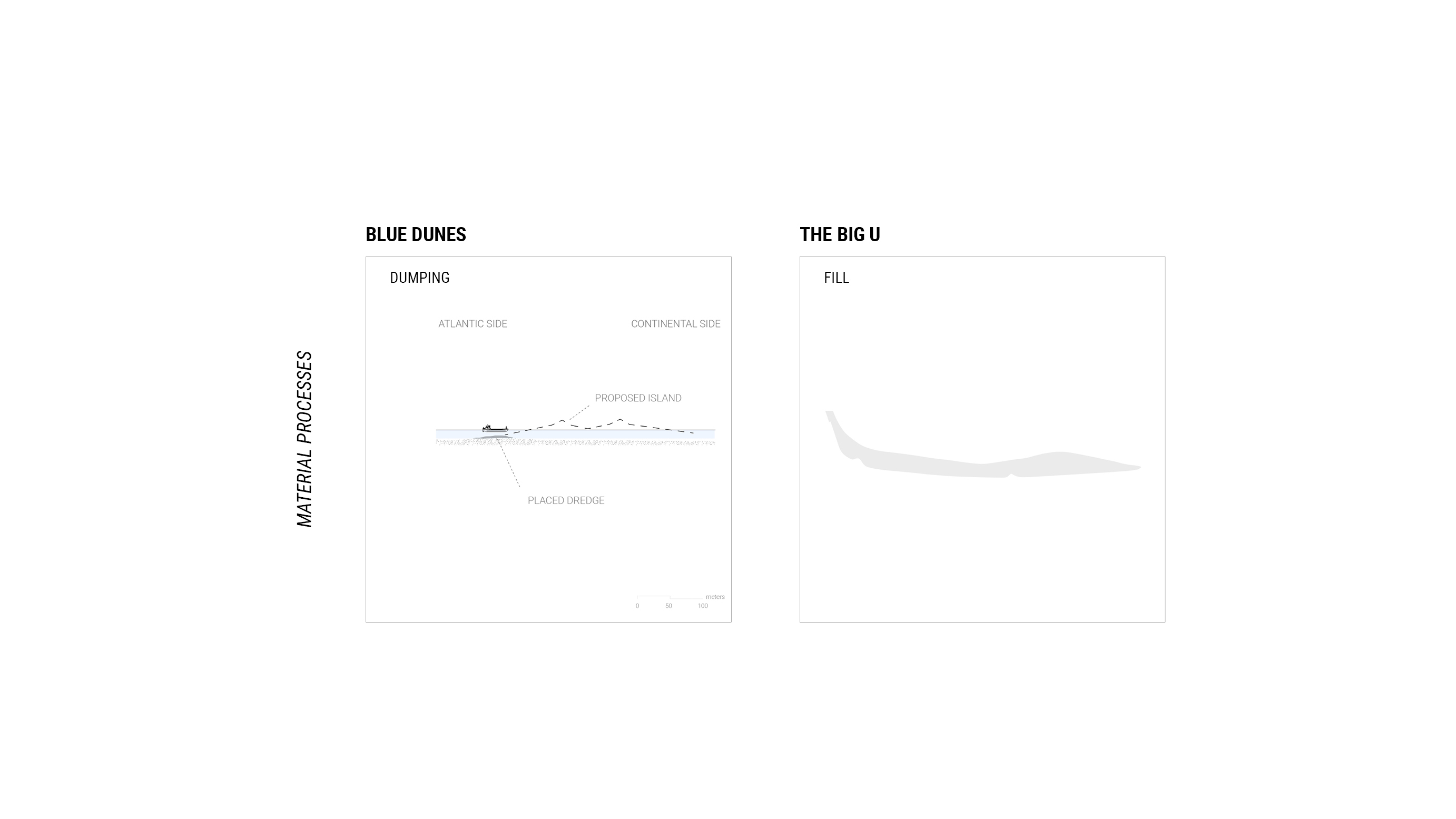

Blue Dunes is a proposal by West 8, WXY Architecture, and various collaborators, centered on building a chain of islands off the New York Harbor, ending at the edges of Long Island and New Jersey. The proposed barrier islands would not only protect the city from increasingly frequent and intense storms but would also be planted with erosion resistant vegetation and accessible to the public as new recreational space in the city.

The Blue Dunes proposal, which made it to the final round of the competition though did not ultimately win, received input from scientists, engineers, planners, economists, and maritime experts. Their contributions led West 8 and WXY Architects to propose the creation of a Blue Dunes Research Initiative dedicated to understanding how barrier islands work from the perspective of physical ocean dynamics, geomorphology and animal habitats.

The human-made/artificial barriers proposed by the Blue Dunes Research Initiative would be built out of material dredged from the sea floor within 5-10 kilometers of the site and made to mimic the geomorphology of coastal dunes and their associated ecological processes and biodiversity. The Blue Dunes project addresses inundation due to storm surge events, but does not address longer-term issues of sea level rise. For this, the design team proposes that this large scale project would work in conjunction with smaller protection projects along existing inhabited coasts.

The project’s multidisciplinary approach attempts to demonstrate landscape architecture’s ability to bring different professions together to design a complex project. However, with that complexity comes logistical challenges including securing cooperation among various stakeholders and across distinct jurisdictions. For instance, federal cooperation would be required to maintain dredging operations and to subsidize state-level insurance premiums for coastal properties.

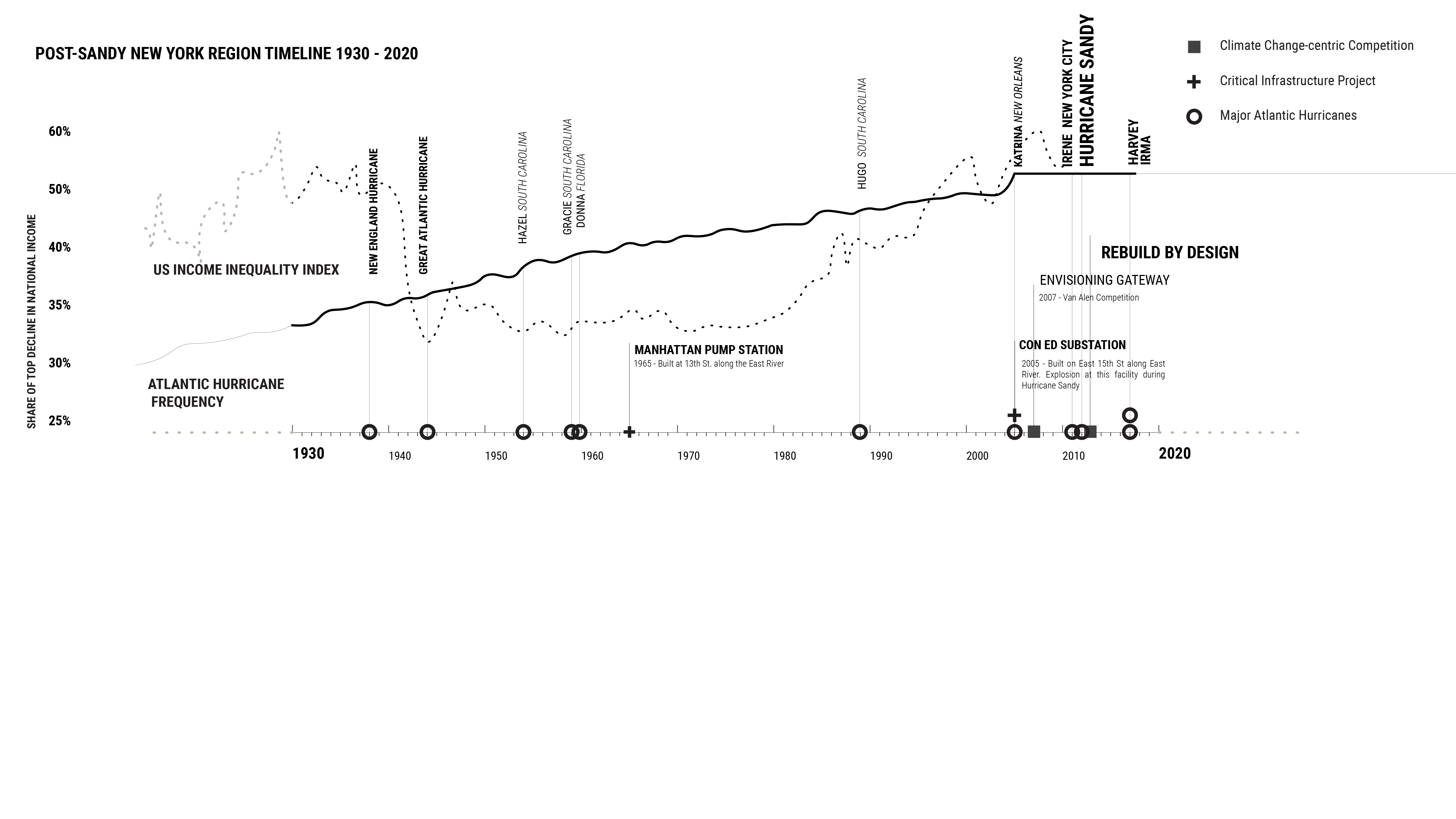

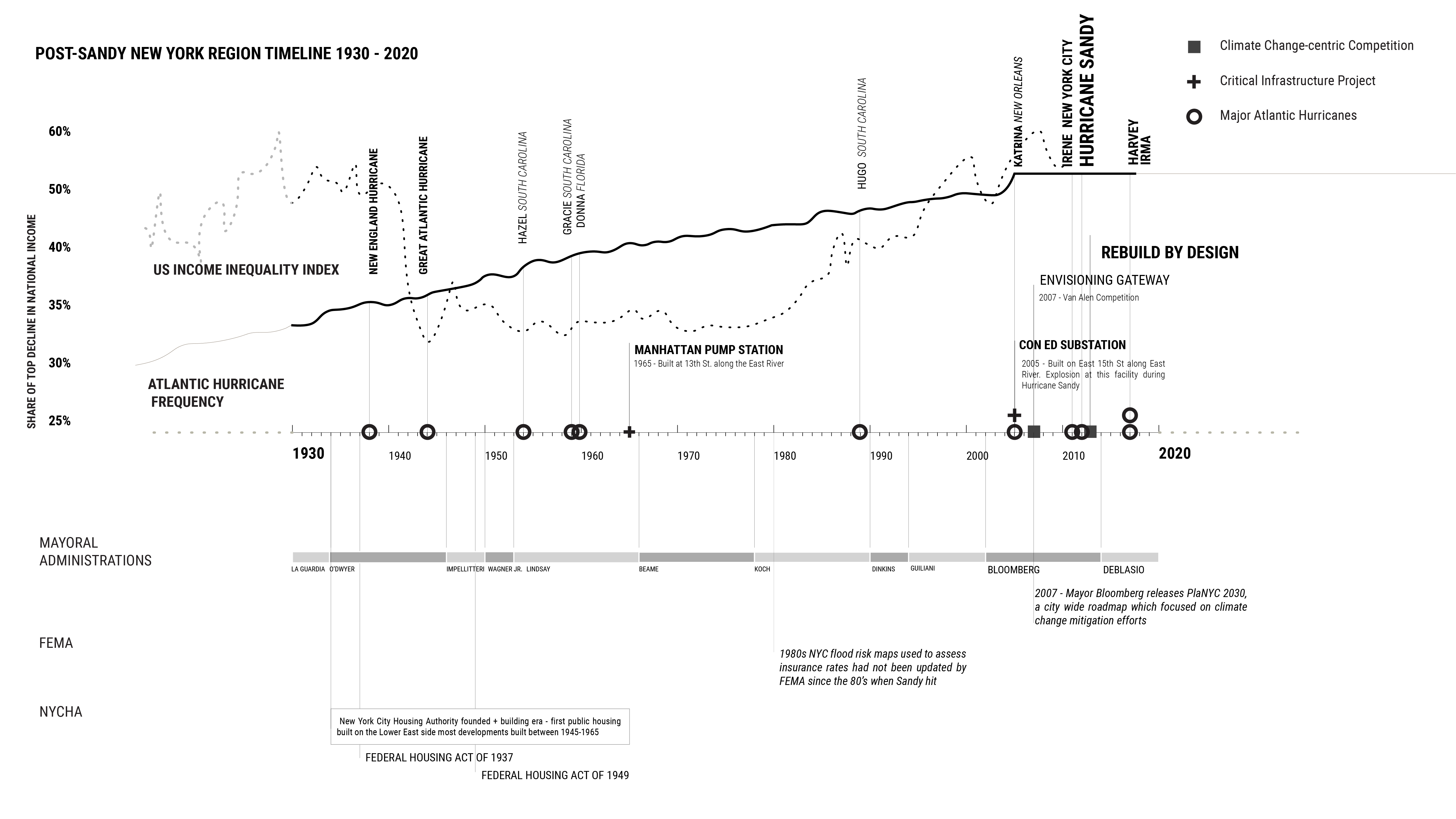

PRE-SANDY/POST-SANDY TIMELINE

Crisis in Context

The damage caused by Hurricane Sandy sparked intense interest in climate change planning and climate resilient design in the New York City region. At the same time, both the storm damage and administrative efforts to rebuild coastal areas seem to have exacerbated long-standing inequities in the area. A timeline of the city’s efforts to rebuild coastal areas after Sandy reveals that funding priorities followed existing patterns of inequitable and uneven distribution, project proposals were more individualistic and less collaborative than they could have been, and fast-moving deadlines encouraged rebuilding to the way things were before the storm rather than addressing the problems that had made communities vulnerable to begin with.

SCALAR COMPARISON

Comparing BIG U + Blue Dunes

The Blue Dunes and the Big U proposals are visually represented by their respective architecture firms in a variety of ways. By examining the projects through a one to one comparison, we can better understand the landscape techniques and details (including scale, material, and construction processes) often obscured by promotional renderings.

CONCLUSIONS

Viewpoints of Hurricane Sandy’s Spatial Legacy

“Starting this fall, New York City will demolish our big, beloved park on the unwealthy (sic) side of the Lower East Side and East Village. Everything must go–shady lawns, picnic areas, ballfields, running track, amphitheater, the compost yard, historic buildings, and 1,000 trees… The city will build a 1.2 mile sea wall and cover the park with eight feet of landfill for flood control. It will also cause a health crisis for our already suffering neighborhood with many people of color, elderly and low-income residents. It is an environmental disaster and an environmental injustice.” – East River Park Action on the East Side Coastal Resiliency Project phase of the BIG U

“Taken in this context, the rewilding of three small neighborhoods along Staten Island’s waterfront seems like just a drop in the bucket. But this new process of planned relocation may soon encompass much larger swaths of land as coastal areas become increasingly uninhabitable and humans are forced to relocate away from densely populated waterways.” – Nathan Kensinger, Photographer and Filmmaker, in Curbed New York

“...although FEMA does not track where people go following voluntary buyouts, an independent study of 323 buyout participants post-Sandy found that over 20 percent moved to areas with flood hazards at least as high as their original locations, and 321 of 323 moved to neighbourhoods with higher poverty levels.” – A.R. Sider in "Social justice implications of US managed retreat buyout programs”

Viewpoints on Rebuild by Design

“Can a design competition be considered a success if it fails to deliver projects that wouldn’t otherwise have materialized? Should we replicate this model — which has spurred intense rivalry between communities for limited resources, perpetuated a cycle of public officials over-promising results to vulnerable residents, and exacerbated planning fatigue — and export it to other places? Should we be running splashy contests in coastal cities saturated with design talent, places that will devise climate adaptation plans with or without HUD and Rockefeller, as the rest of the nation drowns and burns? In capitalist democracies, there is typically a short window for completing major infrastructure projects in the post-disaster period, when national funding pours in and the complex politics of managed retreat and urban development are temporarily shaken up. Cities that get a chance to make a generational investment in infrastructure, resettlement, and equitable adaptation cannot afford to squander it.” – Billy Fleming, Director of the Ian McHarg Center, Faculty at Weitzman School of Design, in ”Design and the Green New Deal” Places Journal, 2019

“Today, most of Rebuild by Design’s winners are substantially funded and moving methodically from design to approval to construction. As the projects take shape, Rebuild has come to represent an unconventional but important approach to governance, demonstrating how enlightened political thinking can improve the built environment – a lesson that has taken on new urgency in the aftermath of the recent presidential election.” – Karrie Jacobs, Editor at Architect Magazine, in “Rebuild by Design’s Enduring Legacy” Architect Magazine

Viewpoints on New York City’s Resilience

“Rep. Max Rose (D-Brooklyn, Staten Island, Brooklyn) suggested that [New York City Mayor Bill] de Blasio spent too much time touting flood prevention efforts in Lower Manhattan before the storm [Hurricane Isaias] at the expense of much of the rest of the boroughs. Council-member Justin Brannan (D-Brooklyn) who represents the Dyker Heights and Bay Ridge neighborhoods in south Brooklyn has pushed for the city’s utility company Con Edison to bury their power lines so as to reduce risk of fire during major storms. ‘Resiliency needs to be holistic,’ tweeted Brannan..” – Clifford Mitchell in “Isaias Delivers Power Outages and Powerful Reminder of NYC’s Vulnerability, Years After Superstorm Sandy” The City

“We tell ‘A Tale of Two Sandys’ to characterize these two genres: on one hand, the crisis was seen as a weather event that created physical and economic damage, and temporarily moved New York City away from its status quo; on the other hand, Hurricane Sandy exacerbated crises which existed before the storm and continued afterwards in heightened form, including poverty, lack of affordable housing, precarious or low employment, and unequal access to resources generally” – “A Tale of Two Sandys” 2013

“As New Yorkers, we cannot and will not abandon our waterfront. It’s one of our greatest assets. We must protect it, not retreat from it” – Mayor Michael Bloomberg, mayor when Hurricane Sandy hit New York in 2012, in 2013

“Dutch models are simply accepted as best practices, or even as ‘portable solutions’ that can be applied in any context around the world. We need more ‘counterplans’ that give voice to the vulnerable, elevate local knowledge, and reveal alternative models of resilience. - Lizzie Yarina in “Your Sea Wall Can’t Save Us” Places Journal

SOURCES

Hurricane Sandy:

Cohen, Jarrett. Tracking A Superstorm. NASA. June 6, 2013. https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/11269.

Knutson, Thomas R., Joseph J. Sirutis, Ming Zhao, Robert E. Tuleya, Morris Bender, Gabriel A. Vecchi, Gabriele Villarini, and Daniel Chavas. "Global projections of intense tropical cyclone activity for the late twenty-first century from dynamical downscaling of CMIP5/RCP4. 5 scenarios." Journal of Climate 28, no. 18 (2015): 7203-7224.

Holland, Greg, and Cindy L. Bruyère. "Recent intense hurricane response to global climate change." Climate Dynamics 42, no. 3-4 (2014): 617-627.

NYC Office of Emergency Management. NYC’s Risk Landscape: A Guide to Hazard Mitigation. City of New York. 2015. Accessed September, 2020. www1.nyc.gov/assets/em/downloads/pdf/hazard_mitigation/nycs_risk_landscape_a_guide_to_hazard_mitigation_final.pdf.

Bergren, Erin, Jessica Coffey, Daniel Aldana Cohen, Ned Crowley, Liz Koslov, Max Liboiron, Alexis Merdjanoff, Adam Murphree, and David Wachsmuth. "A Tale of Two Sandys." (2013).

Keenan, Jesse M., David A. King and Derek Willis. “Understanding Conceptual Climate Change Meanings and Preferences of Multi-Actor Professional Leadership in New York.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 18, no. 3 (2015): 261-285.

Al Shaw, Christie Thompson. “Federal Flood Maps Left New York Unprepared for Sandy - and FEMA Knew It.” Accessed September 25, 2020. https://www.propublica.org/article/federal-flood-maps-left-new-york-unprepared-for-sandy-and-fema-knew-it.

Big U:

DuPuis, E. Melanie, and Miriam Greenberg. “The right to the resilient city: progressive politics and the green growth machine in New York City.” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 9, no. 3 (2019): 352-363.

Kensinger, Nathan. “NYC Will Remake the East River Waterfront to Fight Climate Change. It May Not Be Enough.” Curbed NY. October 17, 2019. Accessed July 03, 2020. https://ny.curbed.com/2019/10/17/20918494/nyc-climate-changeeast-Side-coastal-resiliency-photos.

Feldman, Eileen. “The East Side Coastal Resiliency Project Environmental Impact Statement: A Model for the Integration of Coastal Protection into Livable Spaces.” Water Center. University of Pennsylvania, March 19, 2020. https://watercenter.sas.upenn.edu/the-east-side-coastal-resiliency-project-environmental-impact-statement-a-model-for-the-integration-of-coastal-protection-into-livable-spaces/.

“History and Resources.” East River Park ACTION. Accessed September 25, 2020. https://eastriverparkaction.org/resources/.

Blue Dunes:

Keenan, Jesse M., and Claire Weisz, eds. Blue Dunes: Climate Change by Design. Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2016.

Staten Island:

Siders, Anne R. "Social justice implications of US managed retreat buyout programs." Climatic Change 152, no. 2 (2019): 239-257

Sherry, Virginia N. “$100 Million and Counting for Staten Island Buy-out Program.” SILive, August 29, 2014. https://www.silive.com/eastshore/2014/08/buy-outs.html.

Kensinger, Nathan. “Four Years after Sandy, Staten Island's Shoreline Is Transformed.” Curbed NY. Vox Media, October 27, 2016. https://ny.curbed.com/2016/10/27/13431288/hurricane-sandy-staten-island-wetlands-climate-change.