RWANDA INSTITUTE FOR CONSERVATION AGRICULTURE

Overview

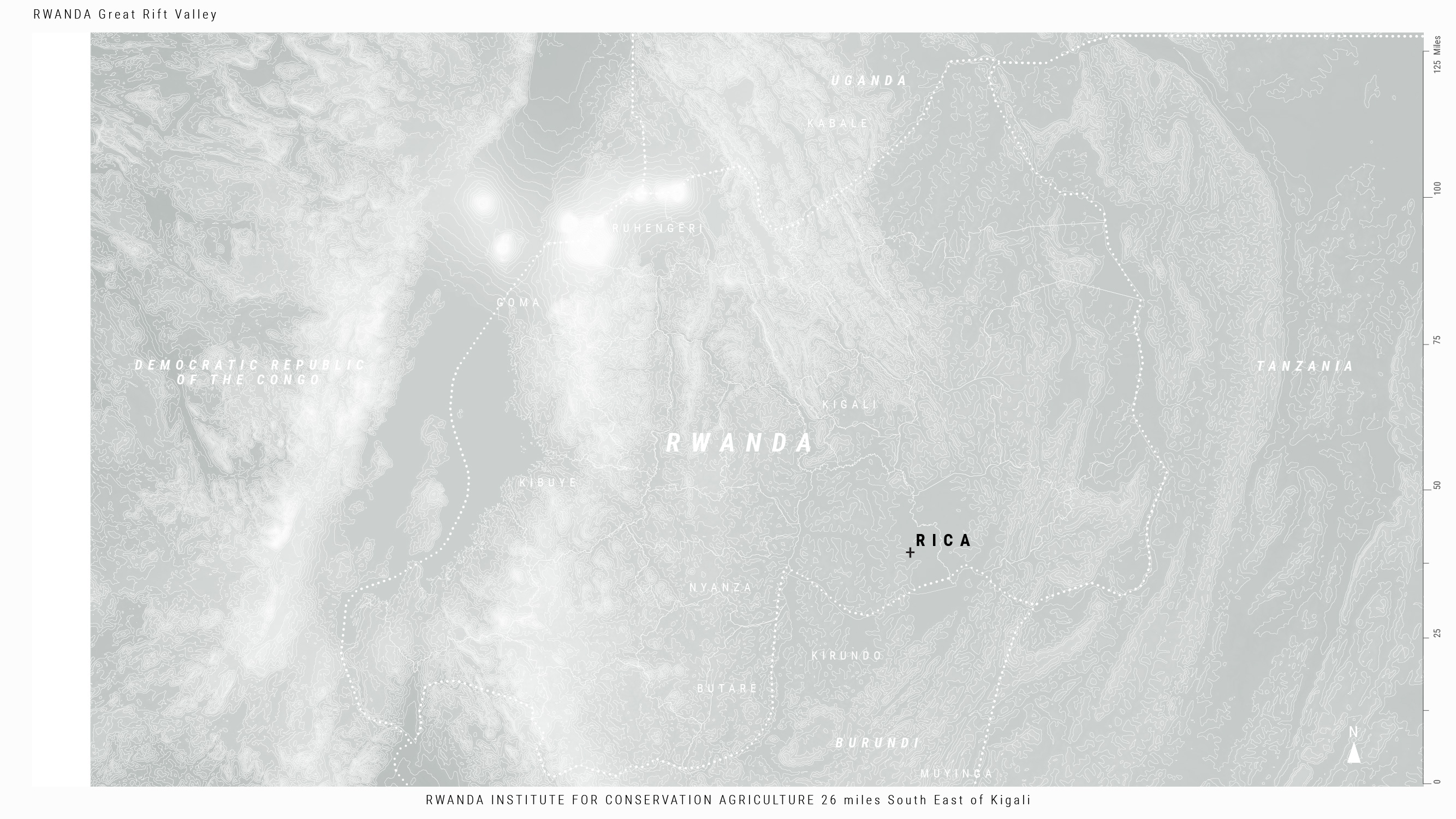

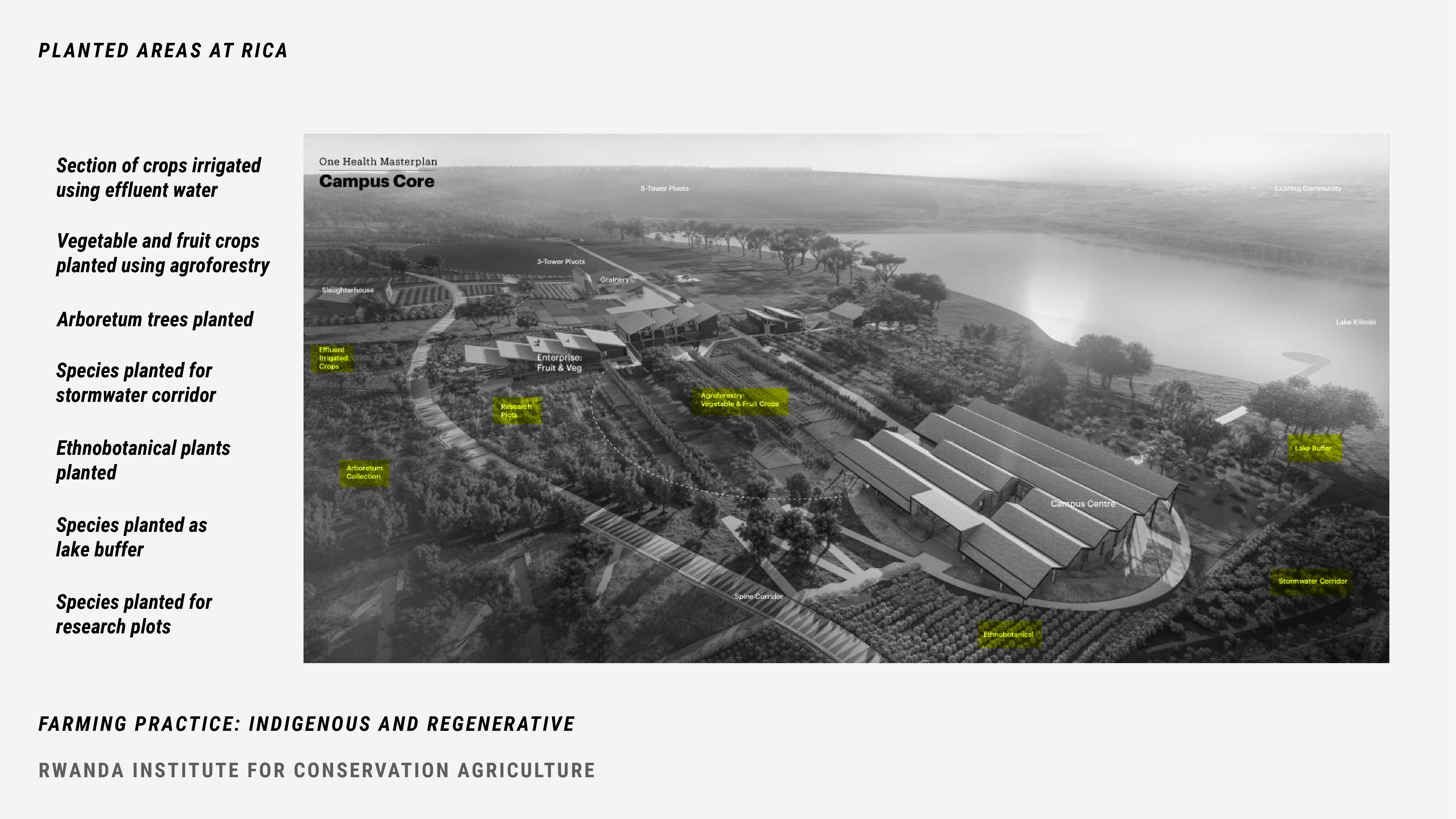

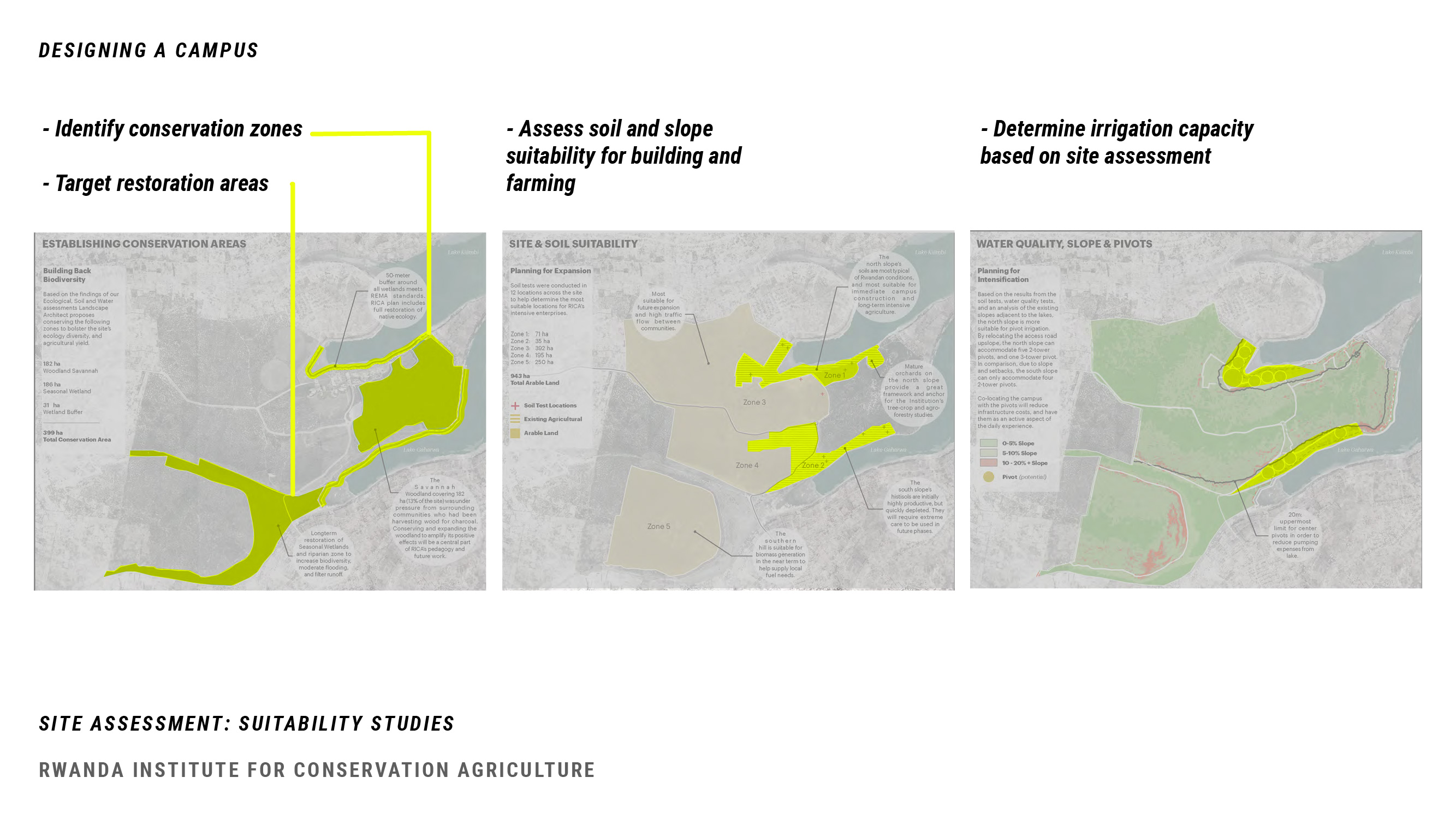

The Rwanda Institute for Conservation Agriculture (RICA) partnered with MASS Design to design and build their new campus in Bugesera, Rwanda, funded through the Howard G. Buffett Foundation. The new campus is a response to the growing problem of food security across Rwanda, due to climate change and increased demand. Rwanda is expected to double in population by 2050. The mission of RICA is to educate young people in Rwanda about creating sustainable food systems as a way to provide food for future generations and transform the farming industry in Rwanda. RICA uses the principles of Conservation Agriculture and One Health, in its educational programming to emphasize the interconnectedness of all species, be it humans, animals or plants. The methodology of the program is hands-on where students learn by doing with an emphasis on incorporating research, community engagement, and other disciplines into the practice of agriculture. The campus is meant to echo the curriculum of the institute by embodying ideas of conservation, biodiversity, and community engagement. Within the campus is a solar farm, water treatment plant and pivot irrigation system. The campus includes not only buildings for classes and housing, but also different agricultural plots for the hands-on learning that is so crucial to the curriculum of the institution. It is the hope of the institute that this new campus will provide the foundation for a bright future for Rwanda’s agriculture industry.

Organizations

• Government of Rwanda: Ministry of Agriculture

• Government of Rwanda: Ministry of Environment

• Howard G. Buffett Foundation

• NASHO Irrigation Cooperative (NAICO)

• ARUP

• Regenerative Design Group

• Remote Group

• MASS Design Group

• PEBL Design

• Government of Rwanda: Ministry of Environment

• Howard G. Buffett Foundation

• NASHO Irrigation Cooperative (NAICO)

• ARUP

• Regenerative Design Group

• Remote Group

• MASS Design Group

• PEBL Design

• Transsolar

Key Terms

MAP

FOOD SECURITY

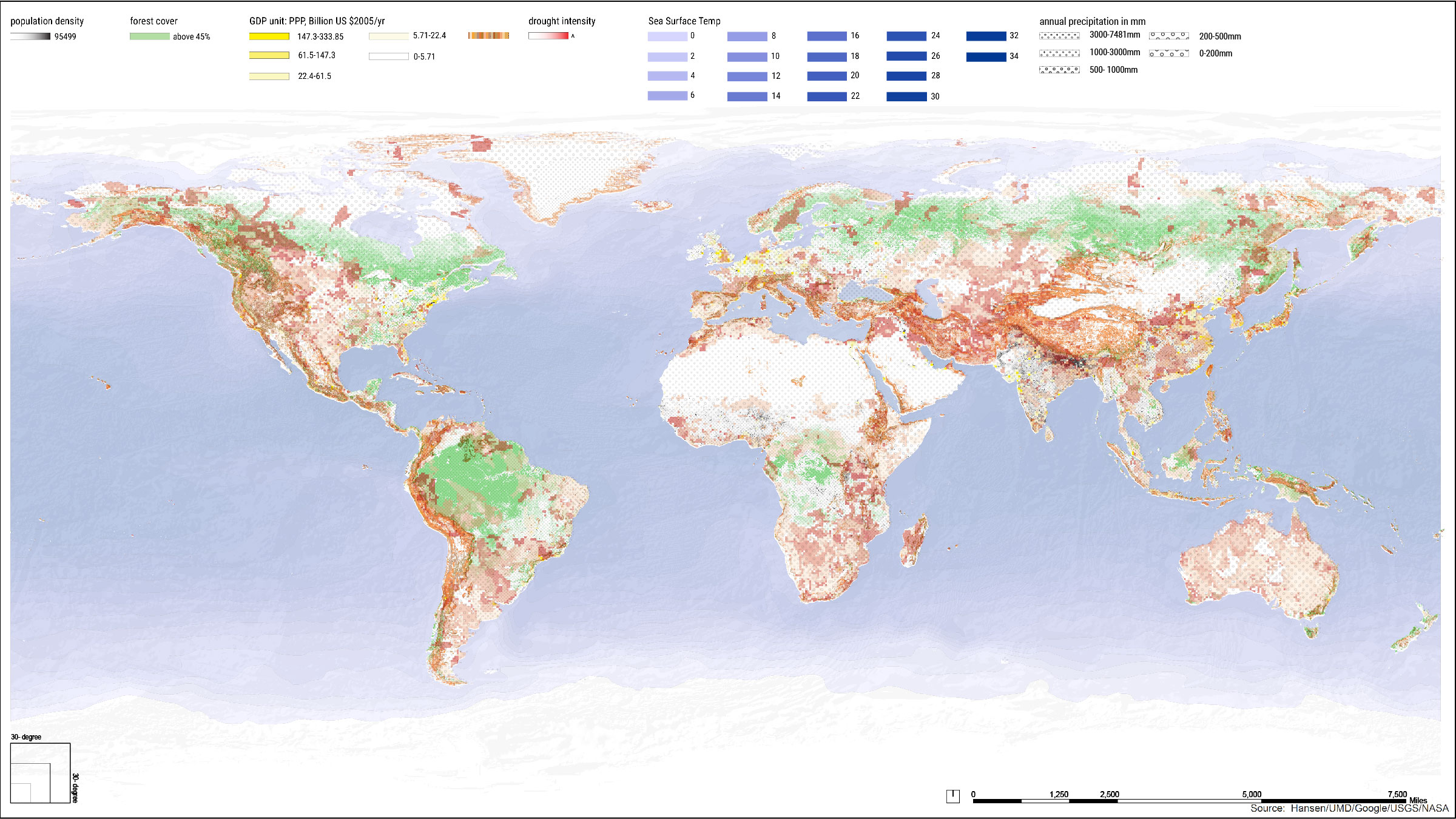

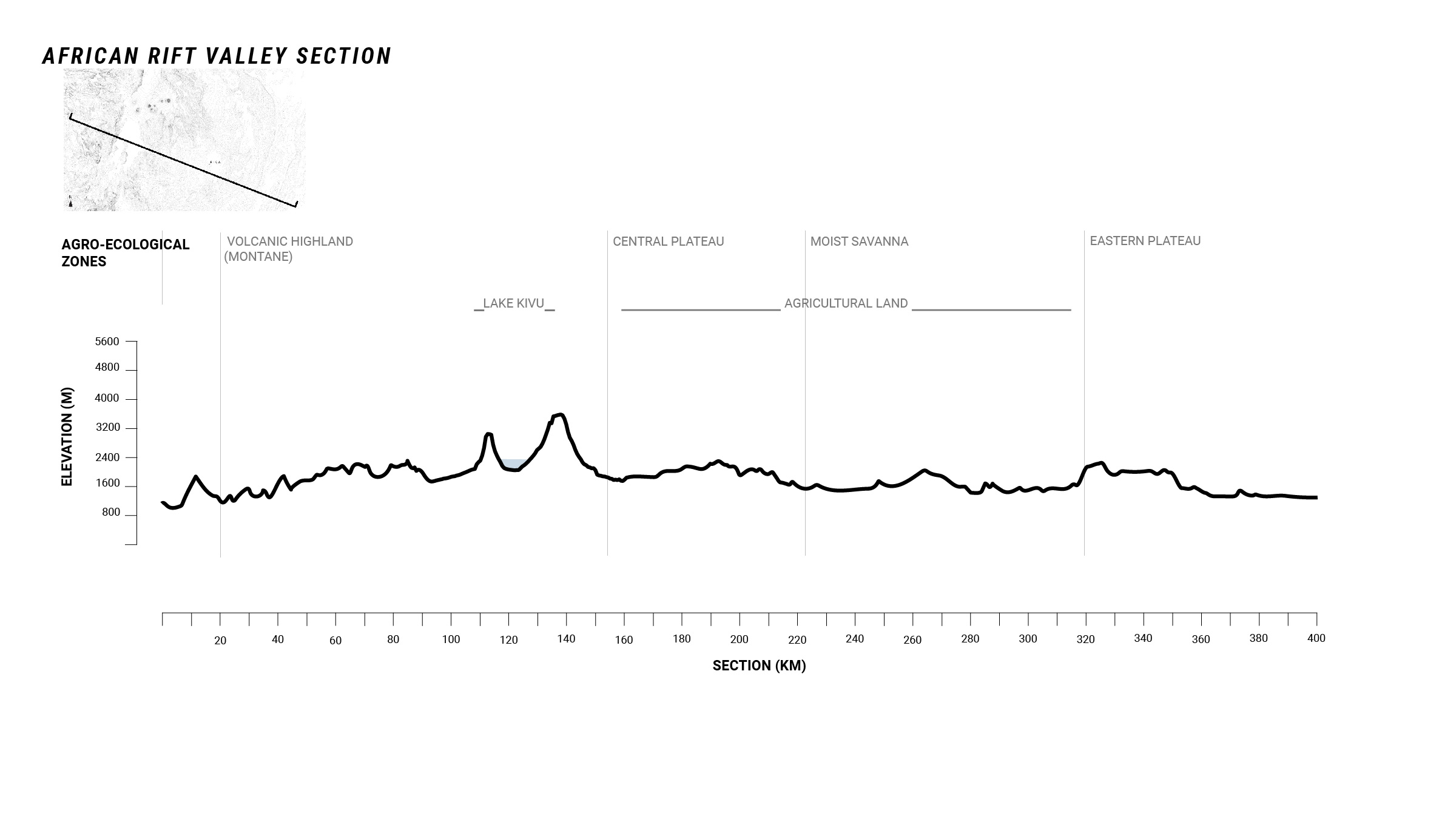

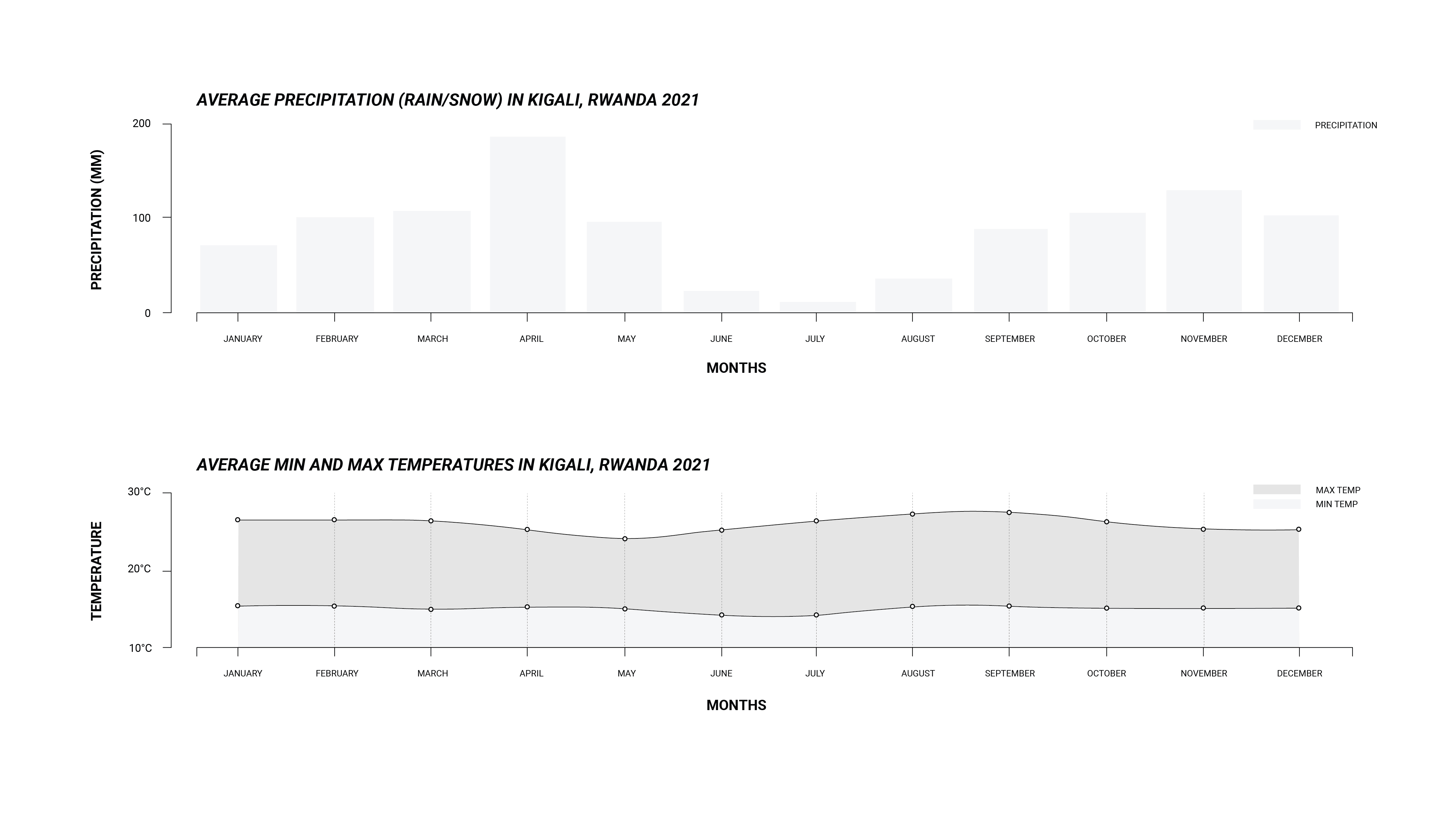

Rwanda is a high altitude country landlocked in the Great Rift Valley. It is the 22nd most densely populated country in the world, and the most densely populated country in mainland Africa. The population is expected to double by 2050. It is also the youngest country in the world, with a largely rural population. This population depends heavily on rain-fed agriculture, which makes the nation severely vulnerable to climate variability, especially shifts in the growing season. While agriculture contributes 40% of the nation’s GDP, 48.7% of the country’s rural population and 22.1% of the urban population are food insecure.

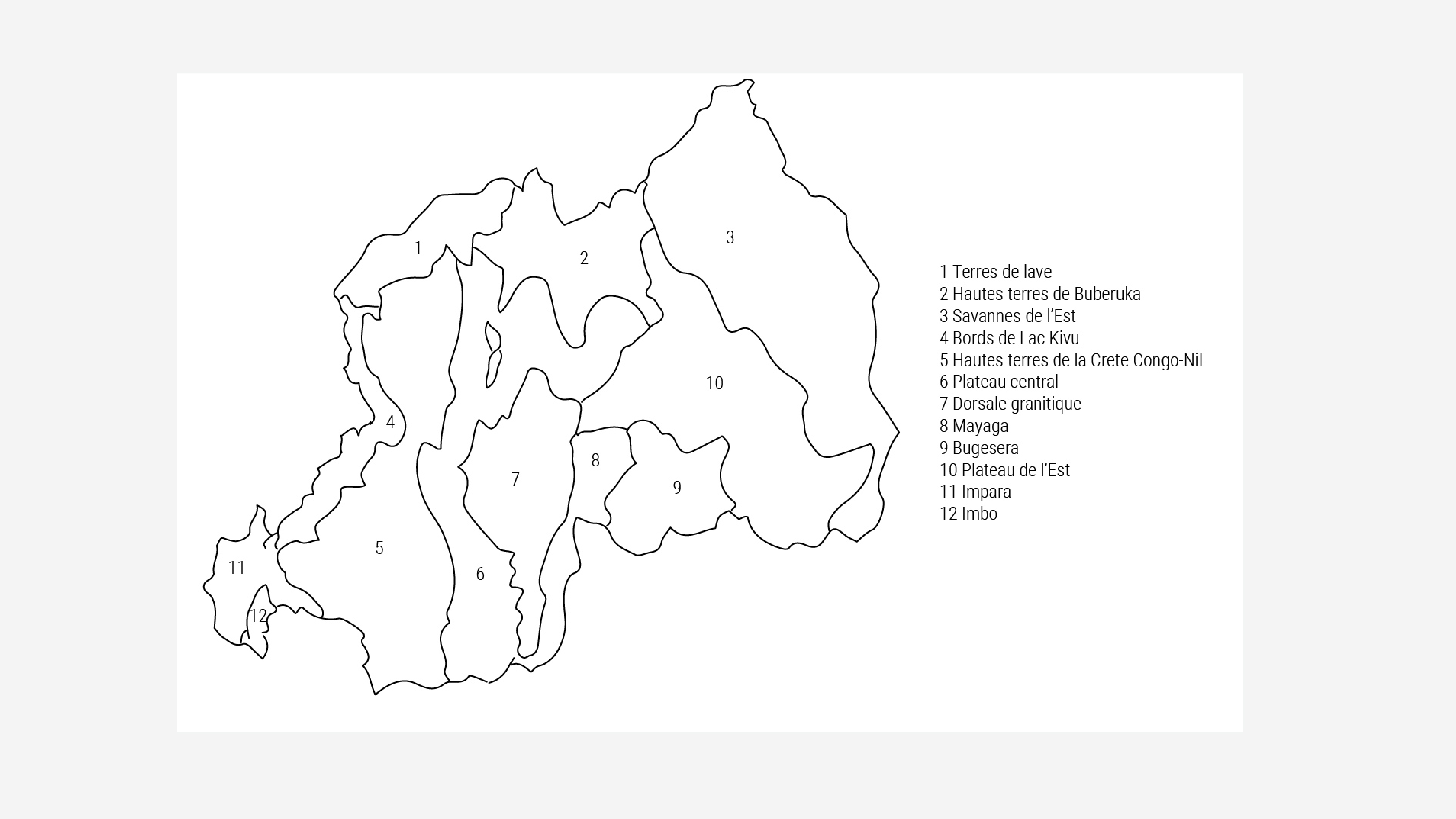

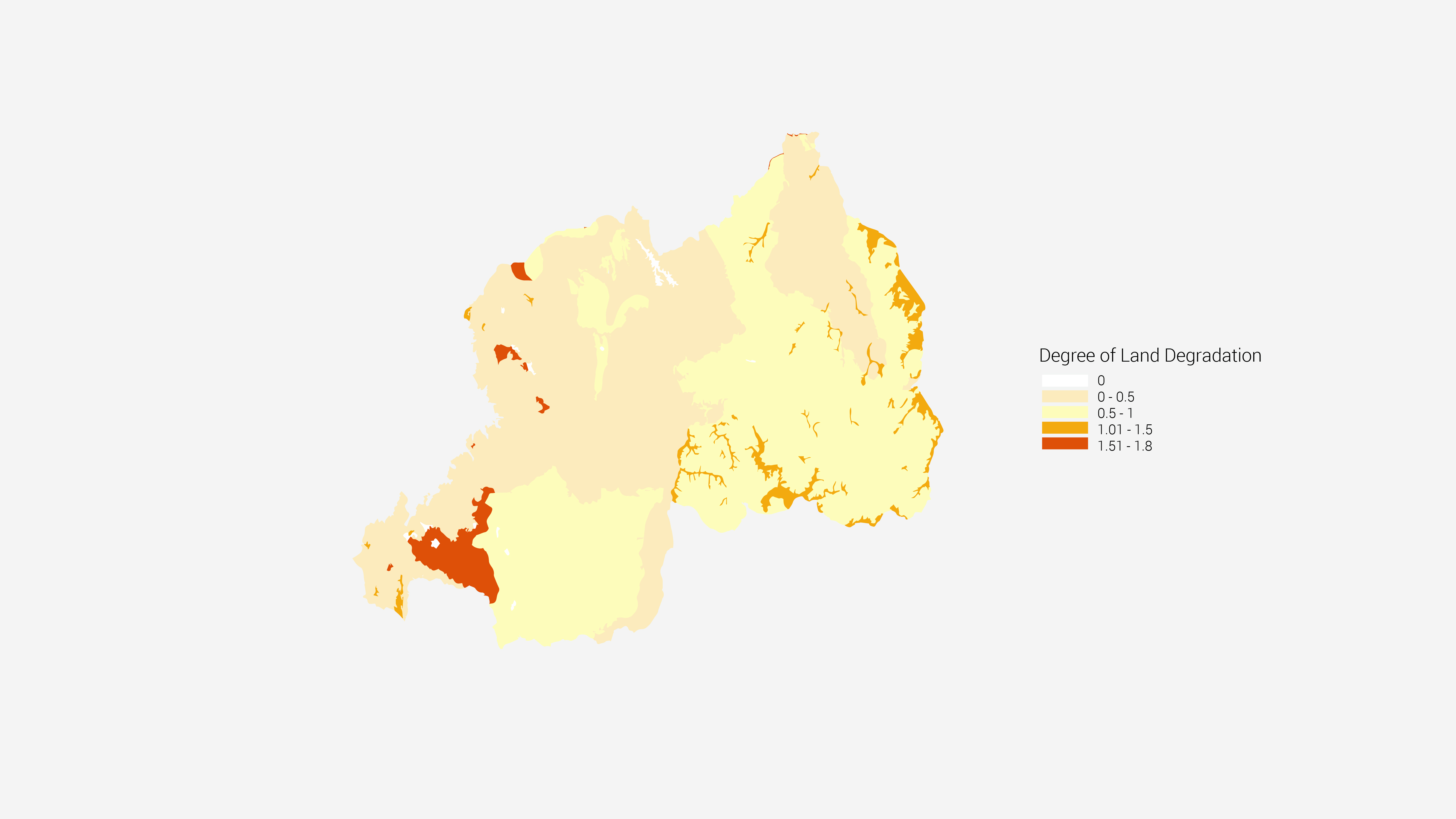

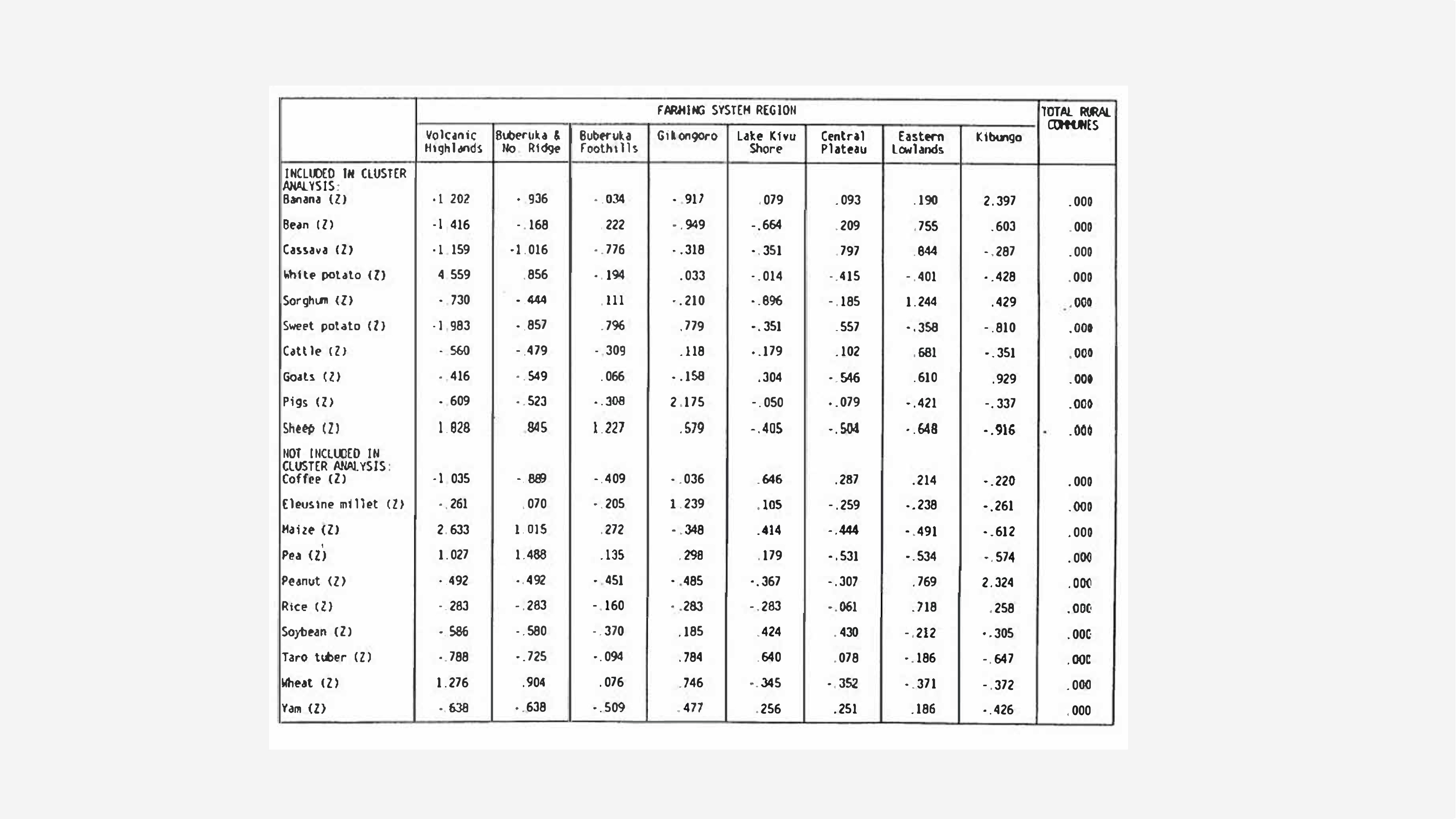

Historically, Rwanda has been geographically divided by Rwandas into customary regions based on ethnic affiliation. Regional agricultural production varies across Rwanda, and shows the influence of cultural, political and economic factors, as well as environmental factors like soil type and sunlight. The farming systems employed in each region still resemble traditional cultural regions, in which the residents of each region decide what crops and animals to plant.

Each region had their own customs and agricultural production. Colonial European cartographers co-opted maps of these traditional regions and mislabeled them for agriculture planning until 1975, when the French agronomist, G. Delepierre created an agro-climatic map with north-south climatic zones based on parallel elevation belts.

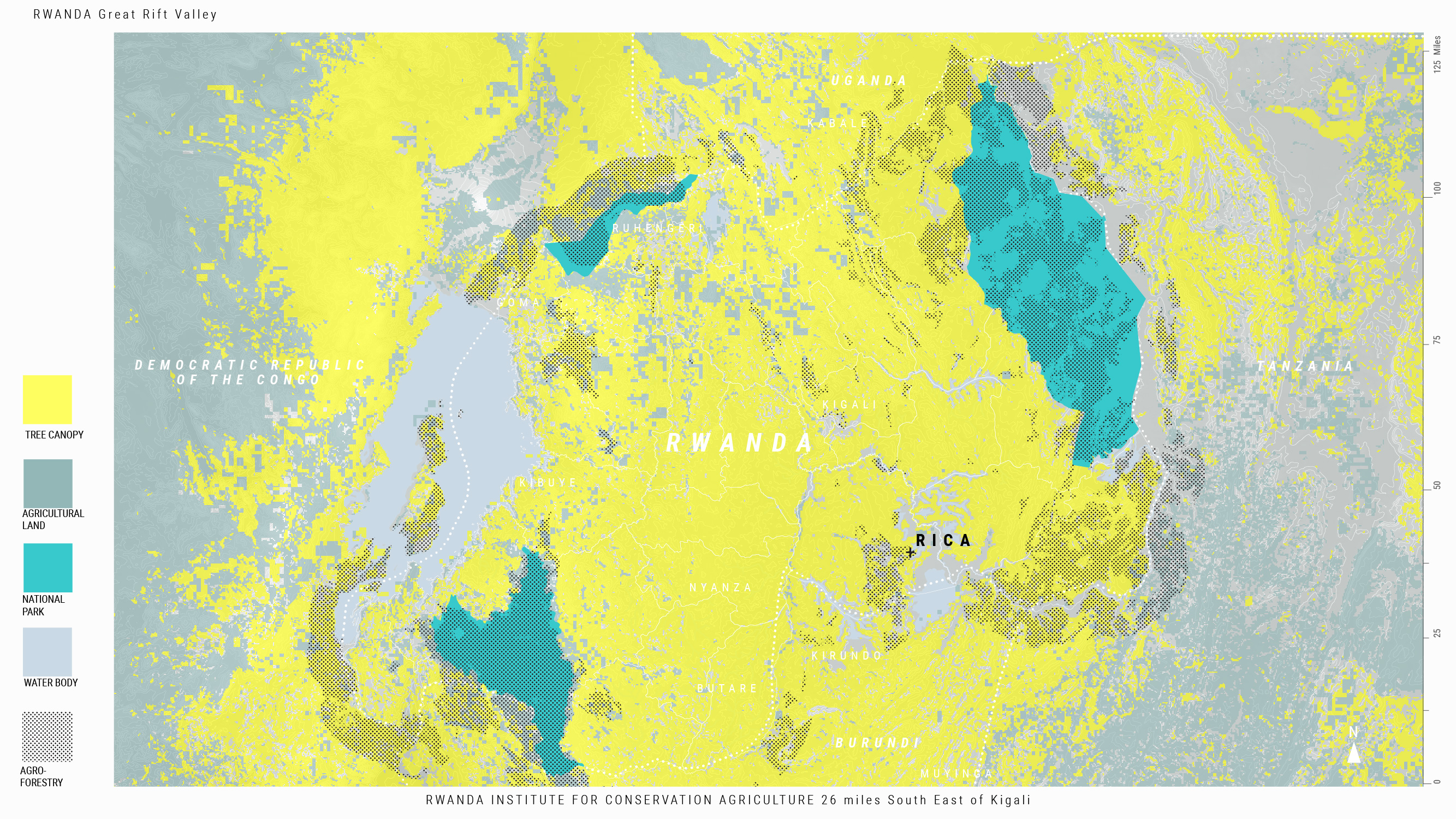

Delepierre’s maps were used to explore crops that could be introduced and grown across the country, replacing indigenous agroforestry and regenerative techniques that Rwandans had used for centuries. These crops, including sweet potatoes, plantains, beans, maize, banana and cassava, were imported by colonists. To cultivate these species, Rwandan farmers used imported pesticides and monocropping to produce larger yields, and deforested large plots of land to plant cash crops in full sun.

The results of these colonial imports are still with the independent nation. The majority of rural farmers farm small plots of less than 0.5 hectares on steep slopes with degraded soils. In 2021, a study in the capital, Kigali, found that only 24.5% of the species available in open-air markets were indigenous to Africa.

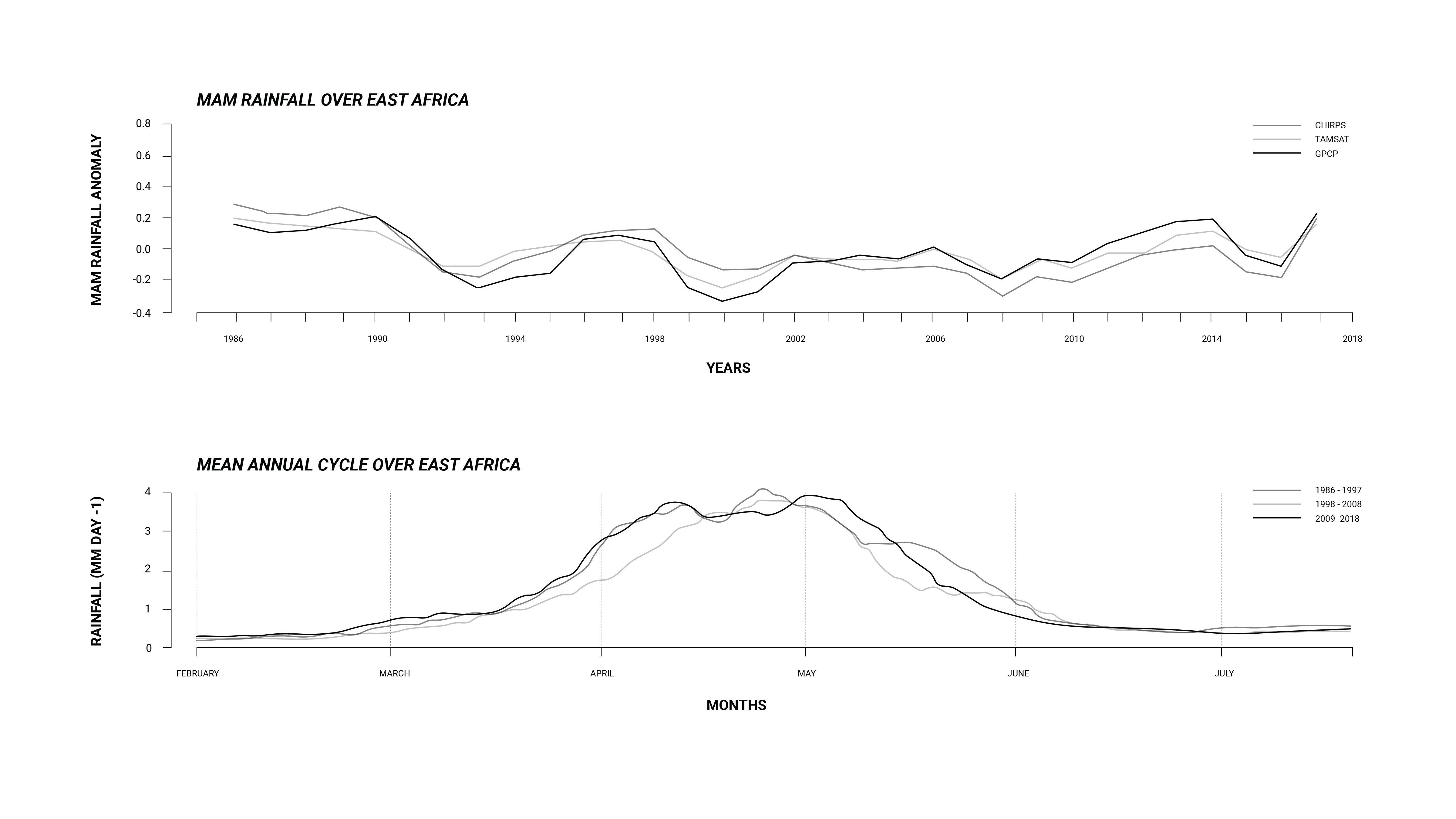

Furthermore, it is projected that east Africa will experience significant and unequal changes in the frequency, intensity and predictability of precipitation, with increased rainfall from December to February and decreased rainfall from June to August. These changes are not expected to be uniform, and will likely occur sporadically, making it difficult to predict and ensure water availability throughout the year. For a nation that relies on rain-fed agriculture, this is a crisis.

REGIONAL CONCERNS

Climate change exacerbates existing concerns over regional security.

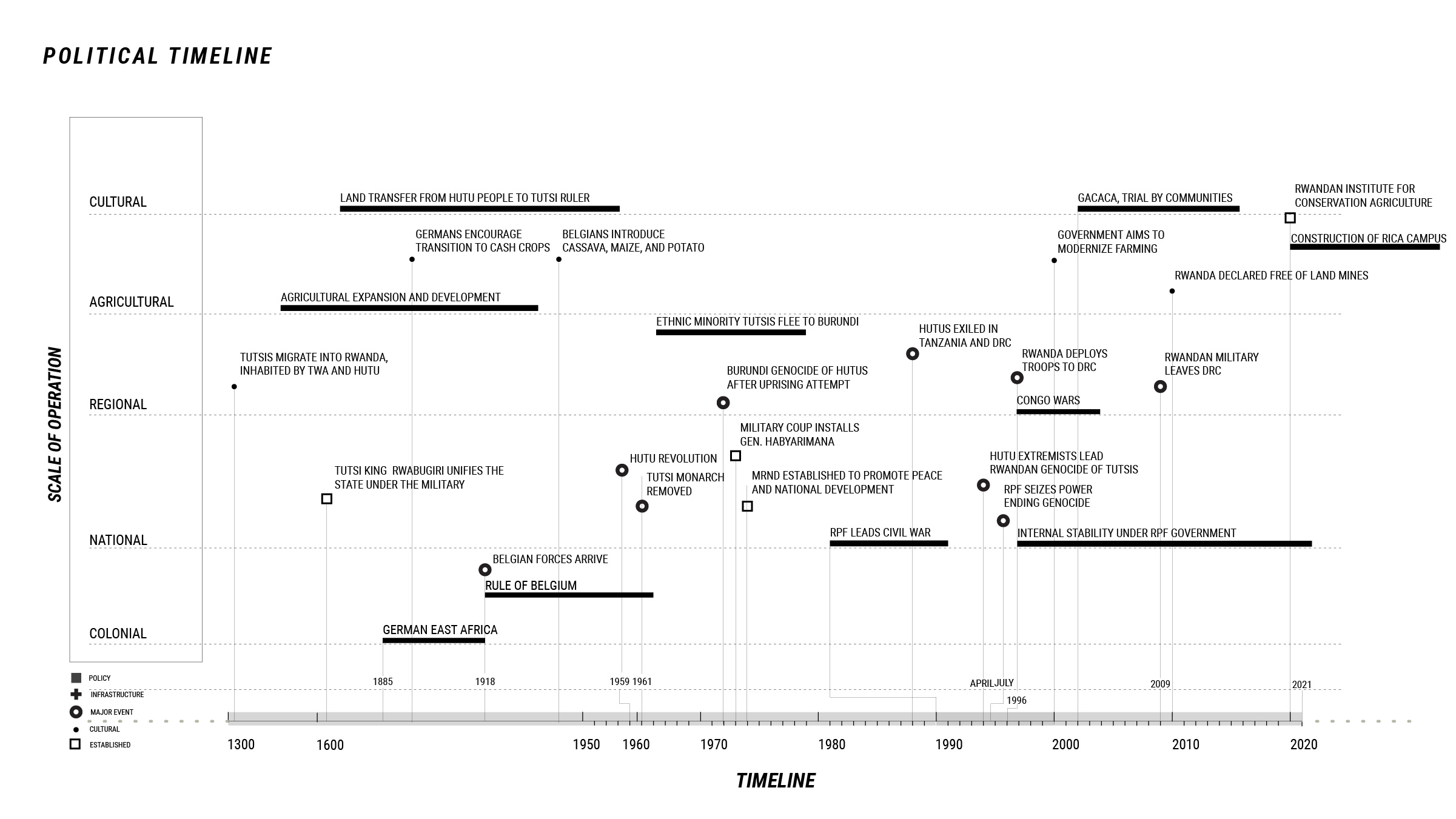

In April 1994, extremist members of the ethnic Hutu majority group orchestrated the Rwandan genocide. Over the course of three months, an estimated 800,000 people were murdered, mostly members of the Tutsi ethnic minority group. The genocide was ended when the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), led by Tutsi refugees living in Uganda, seized power in July 1994. The military leaders of the genocide, alongside many others, escaped to the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), then colonial Zaire. In 1996, Rwanda deployed troops into the DRC, killing many civilians, beginning the First Congo War, and starting years of regional and civil warfare in eastern DRC. In 2013, regional conflict reached a height when the UN investigated Rwanda for backing the DRC-based insurgent group M23, which seized power over the DRC capital of Goma. The DRC remains politically unstable, with a proliferation of armed groups across the country.

Almost three decades later, in 2021, the RPF, led by President Paul Kagame, is still in power. The constitutional republic government has made efforts to improve health, increase agricultural output and food security, and promote women’s empowerment. Rwanda is politically stable in comparison to its neighboring states in eastern Africa, but there is currently no overarching structure for peace and security efforts in the region.

The political instability in the region has made it challenging to regulate and curb habitat destruction, which has led to a significant loss of biodiversity for both cultivated and uncultivated flora and fauna.

FARMING PRACTICE: INDIGENOUS AND REGENERATIVE

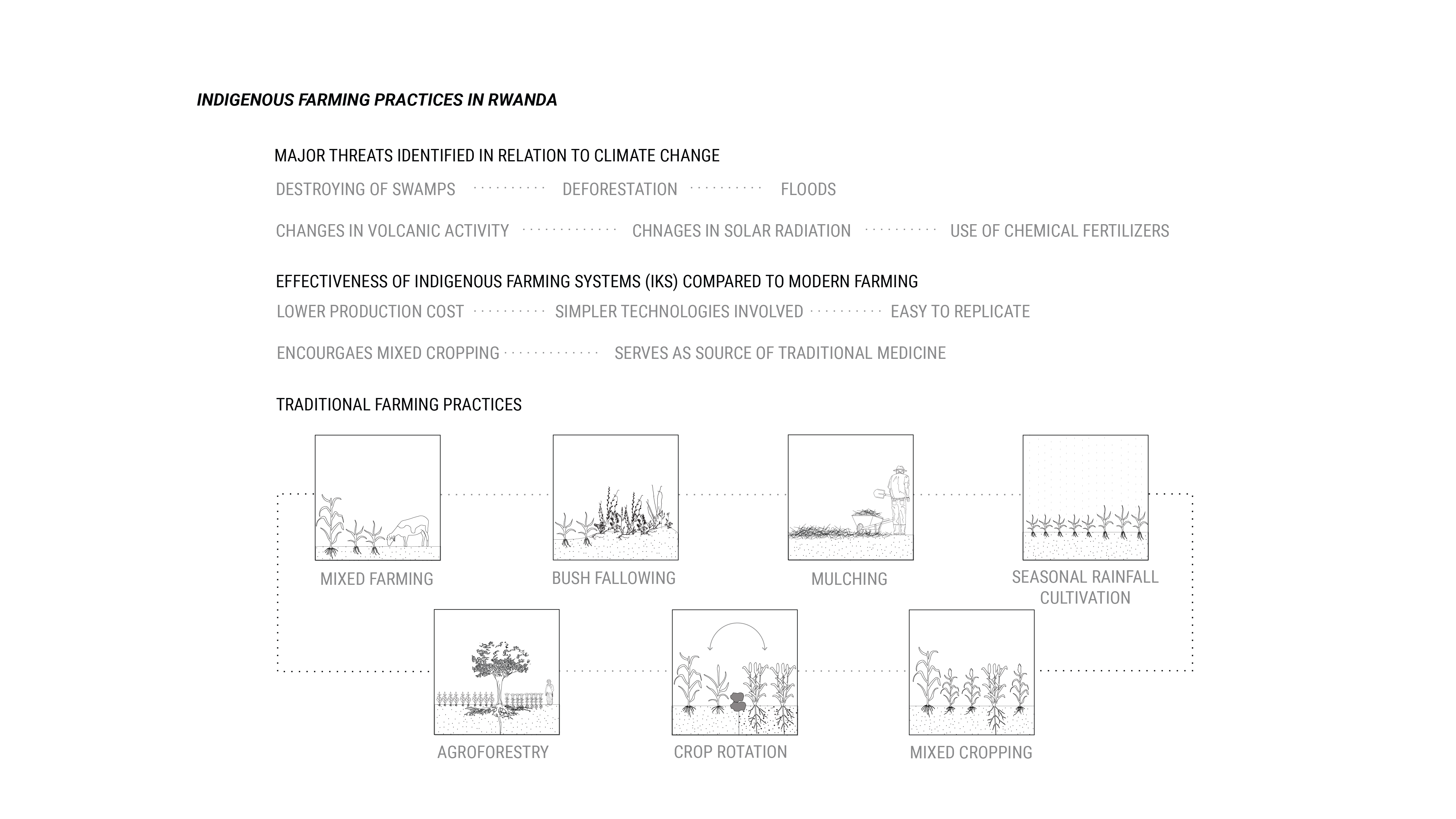

In addition to the loss of biodiversity from habitat destruction, the major consequences of the colonial importation of foreign agricultural practices include the loss of genetic diversity in crops planted as monocultures, soil degradation, and the loss of the traditional knowledge systems. Indigenous agriculture techniques have been passed down orally in Central Africa, and have evolved over generations to be flexible and adaptable to combat environmental change through trial and error. Knowledge erosion is a key threat to indigenous farming practices, as the probability of finding a resource to combat climate change decreases as knowledge is lost across generations.

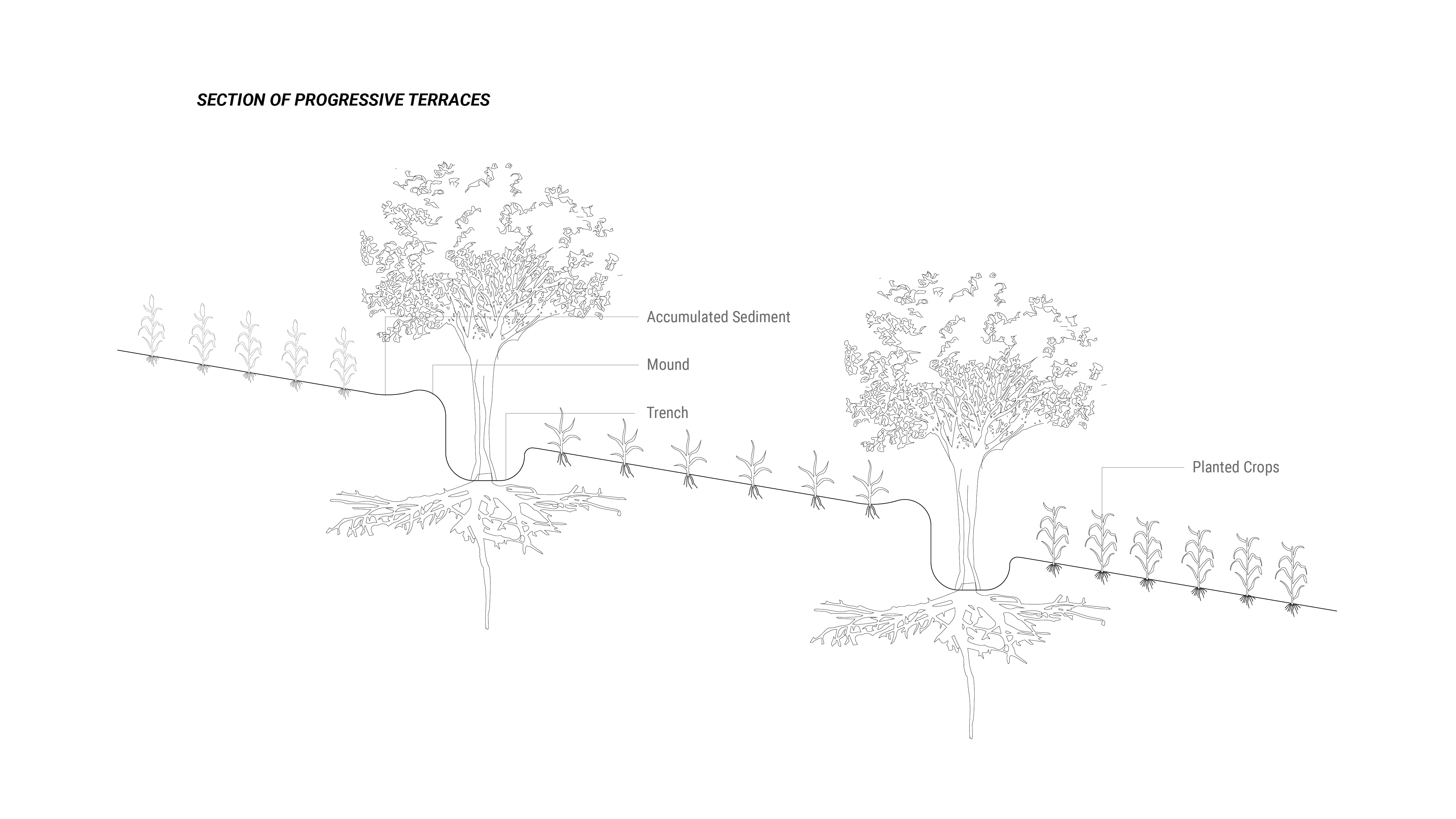

Before colonization, Rwandan smallholders and farmers planted many different species on small plots of land. Indigenous Rwandan farming practices evolved in response to the steep topography throughout the nation. Techniques including ridge building, or terracing, are used. On plateaus, Rwandan farmers create flat top ridges and plant vegetables, maize, groundnuts, round and sweet potatoes and legumes. Contoured ridges prevent soil erosion and retain moisture.

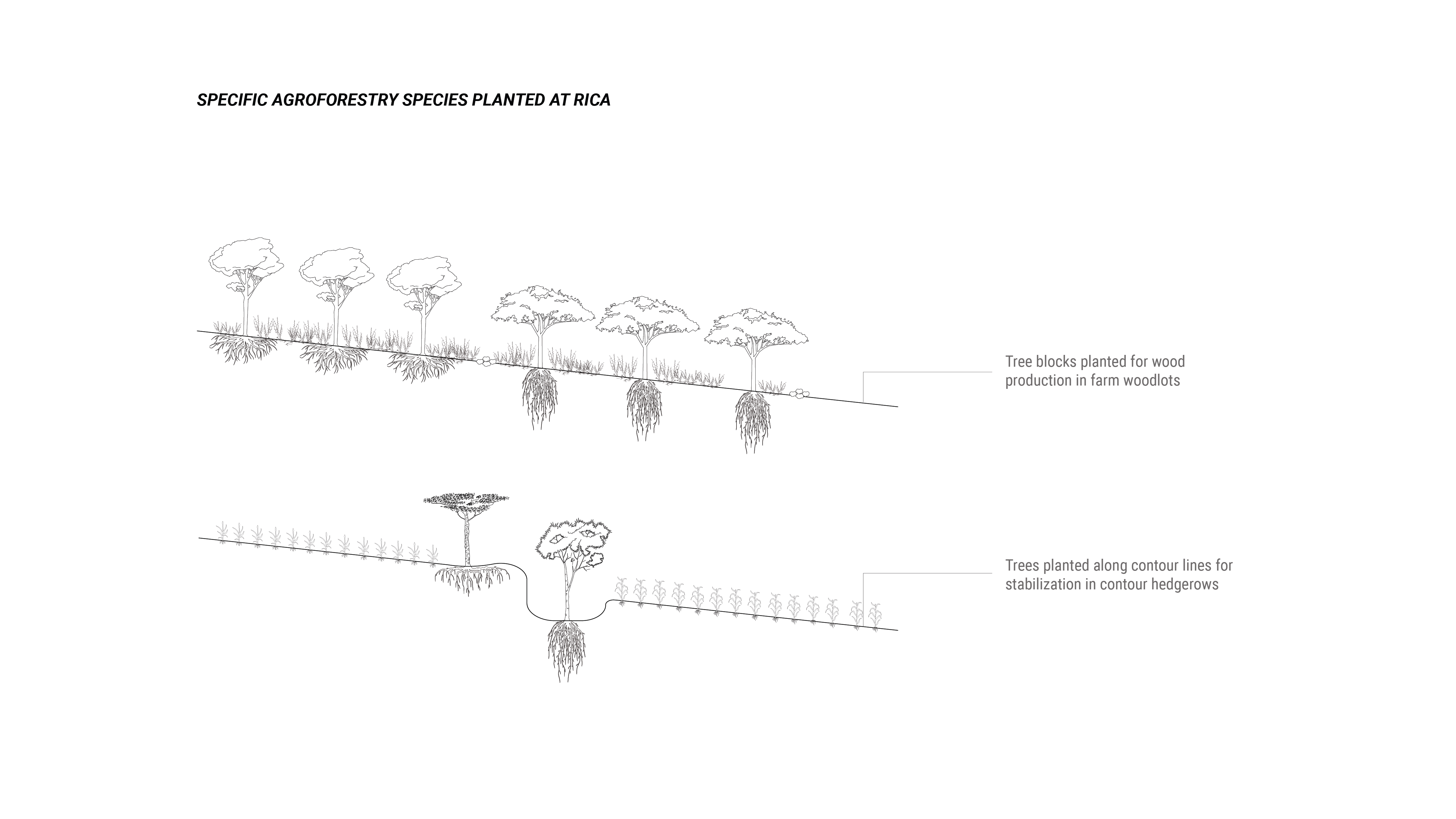

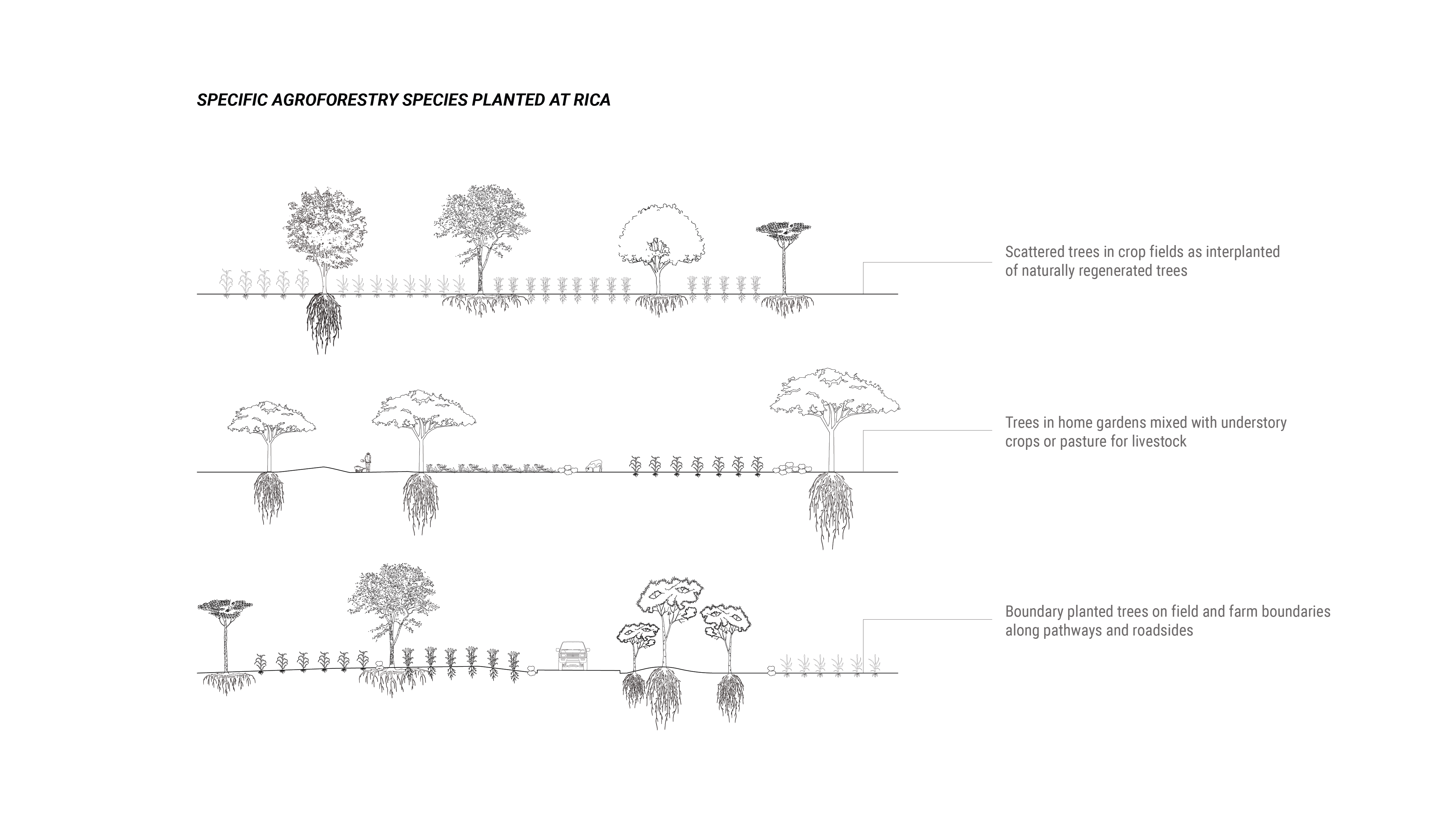

Mixed farming and mixed cropping, including planting different edible and non-edible species together, increases resilience by ensuring that some crops will survive in the event of an environmental disaster like a flood or heatwave. Leguminous plants are usually intercropped with other plants, and planted during fallow periods to increase the nitrogen content in soil. In addition to mixed planting, rotational cropping is common. Beans, Ipomoa, maize and groundnut are commonly planted, followed by cassava, taro and yam tubers. Rwandan farmers also practice agroforestry by integrating animals, including sheep, into pastures with a canopy of trees and shrubs that provide forage for the animals and protect the soil from erosion.

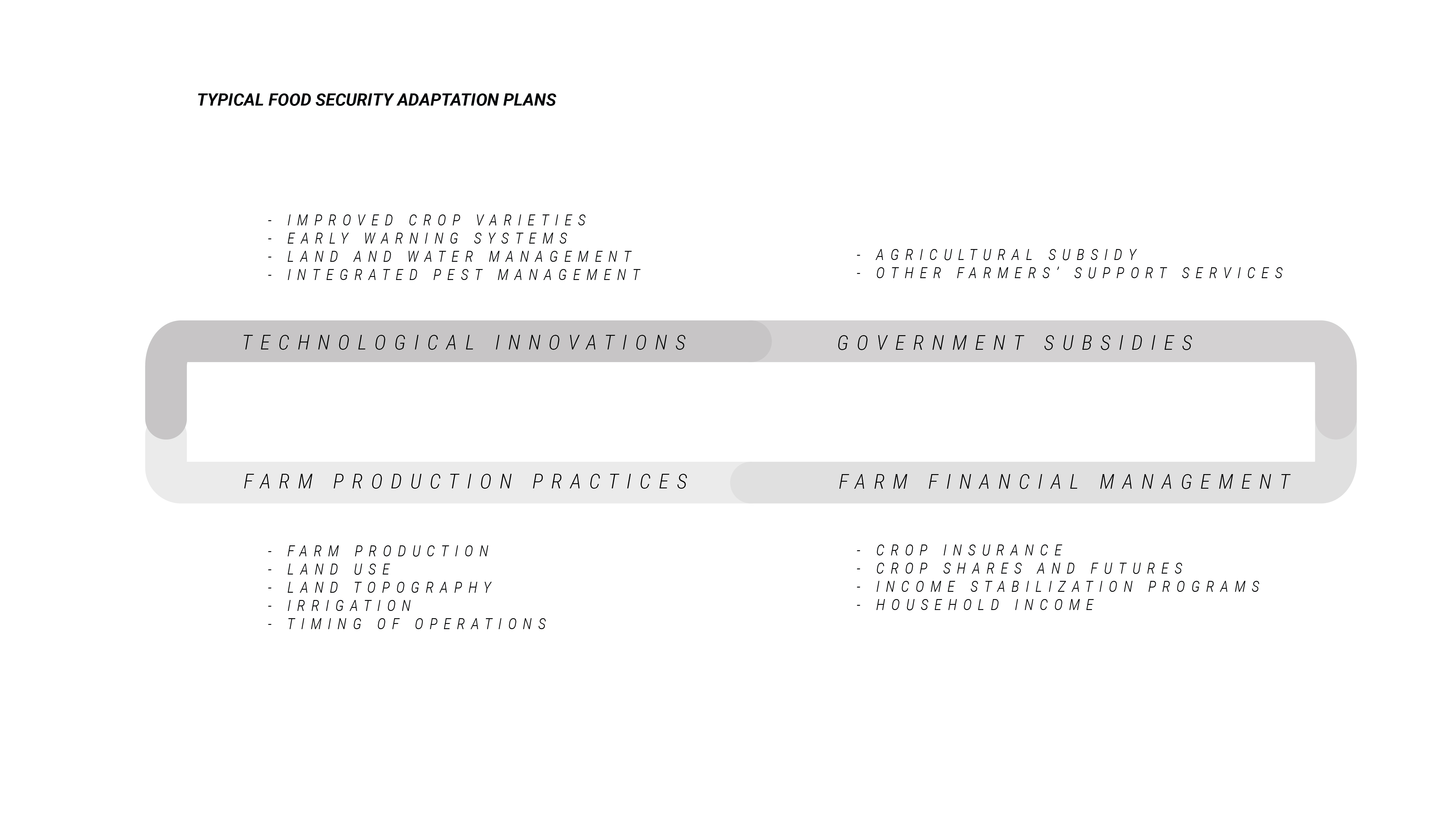

Indigenous knowledge shapes how Rwandan communities interact with their climate, and including these knowledge systems in farming practices can increase farmers' resilience to climate change. The Rwandan government has acknowledged the need to incorporate indigenous knowledge into economic advancement strategies, including farming systems. The Rwandan Institute for Conservation Agriculture (RICA) aids this mission by educating college-aged Rwandans on the campus in Bugesera, Rwanda.

EDUCATIONAL FRAMEWORK

RICA is an undergraduate institution that awards a single degree: a Bachelor of Science in Conservation Agriculture. The school was funded by American philanthropist Howard G. Buffett, who sought to build a land-grant institution in partnership with an African government. Buffett approached President Kagame to build the university in Rwanda due to the unique agricultural challenges and stable government. The school was built as a collaboration between landscape architects, environmental designers and engineers and farmers.

The program focuses on the concept of One Health: that human, ecological and animal health are linked. The curriculum is taught over 3 years, and uses a combination of classroom learning and practical internships, as well as field experience. During the first year, students live on a 2 acre plot of land on campus, where they live a smallholder farmer’s experience alongside 20 classmates. The second year, students are exposed to enterprise scale agribusiness in five different divisions: vegetables, mechanization and irrigation, row and forage crops, dairy and poultry and swine. The third year, the students choose two enterprises to specialize in and work with communities on a practicum project. The school partners with smallholder farmers who are part of the NASHO Irrigation Cooperative (NAICO) in the Eastern Province.

After completing their education, most graduates become entrepreneurs and start their own smallholding agricultural operations. Others manage co-operative agriculture programs, start commercial enterprises to support farmers, or work in government or education roles.

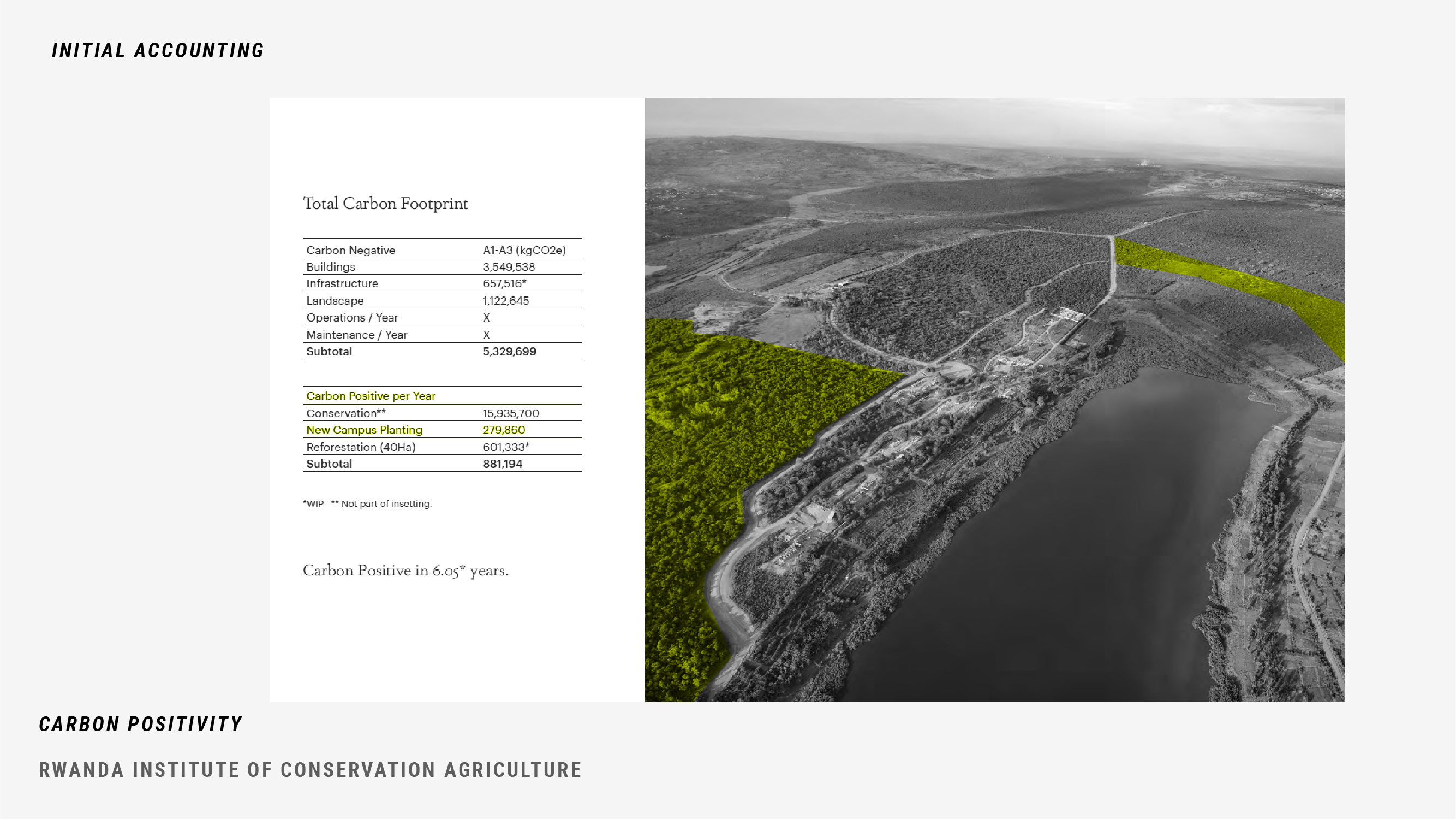

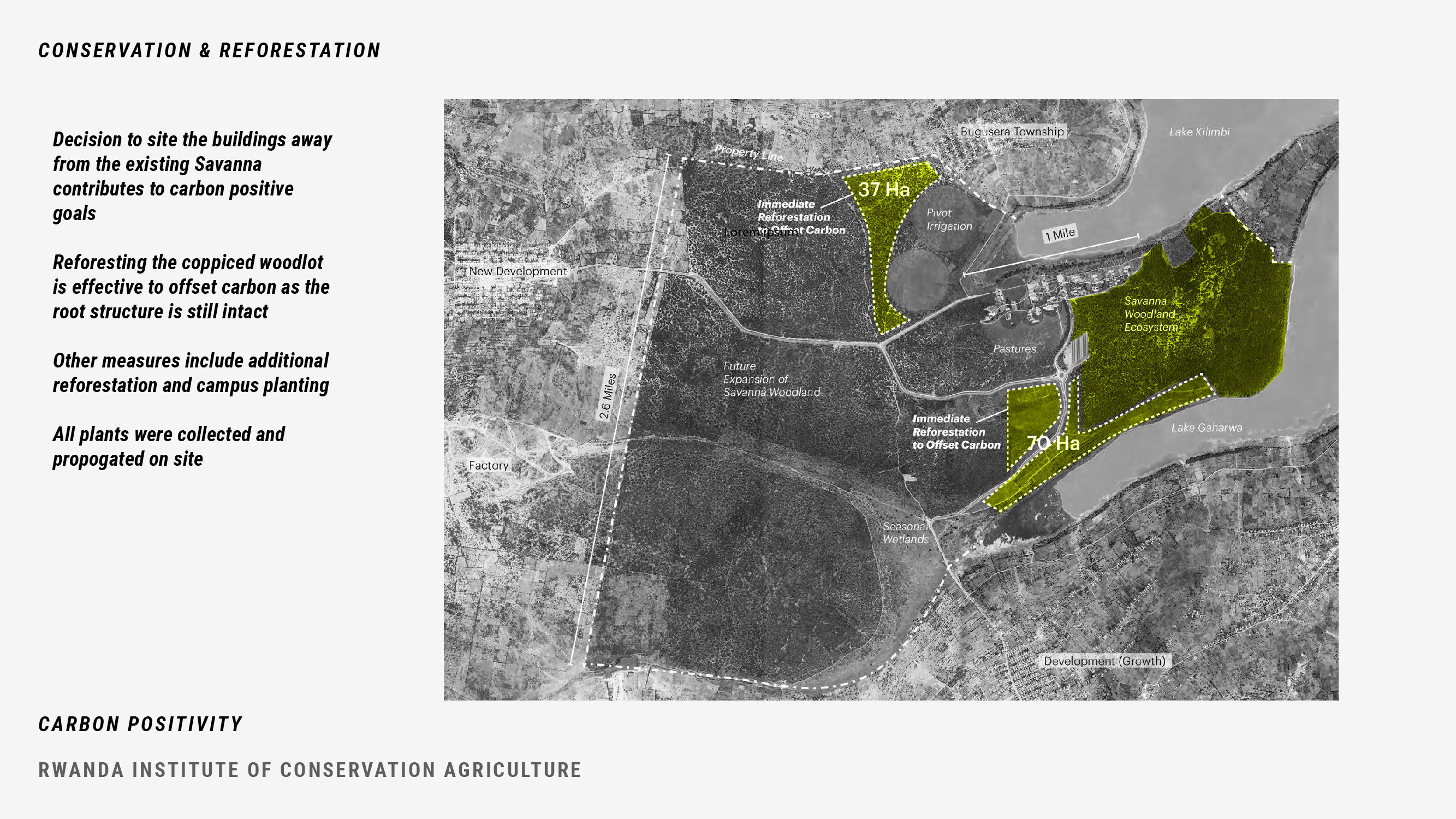

CARBON POSITIVITY

The RICA project connects its educational mission of responsible land management to the development of its own campus. The project has aggressive carbon accounting goals, seeking carbon positivity within less than a decade of operation. Working with the environmental design consultants Atelier Ten, and in consultation with local ecologists, the design team has made a series of decisions to minimize the impact of the project.

First, in the siting of the buildings, the team rejected the initial plan to place the structures under the expansive shade trees of the existing savanna. The decision to conserve existing ecological function and structure was the single most important factor towards carbon positivity. In addition, the team is developing a series of reforestation strategies taking advantage of former woodlots and cleared areas where the root structure is still intact and carbon sequestration can be most effective. In a commitment to supporting local material and labor, nearly all of the materials for the project have been sourced on site and within a short radius. Teams of local craftspeople have built custom fittings and furniture. All seeds and plants have been collected and propagated on site. And the facility is powered by solar energy. The project demonstrates a commitment to local material, labor, energy and to preserving and cultivating the biodiversity of the campus. It is exemplary in its approach to managing resources and building capacity for change on site and beyond. The process has been facilitated by close collaborations across design disciplines. In addition to providing architectural, landscape architectural, engineering, and ecology services in-house, MASS design started a construction company to build the project and controlled the budget. While perhaps not replicable as a project delivery structure, this consolidation has allowed for maximum coordination towards a carbon-positive future.

CONCLUSION

The Rwanda Institute for Conservation Agriculture addresses the national problem of food security by mobilizing students to study agriculture while living and working in collaboration with smallholder farmers on the RICA campus. While the school educates the next generation of farm leadership, it also demonstrates using design thinking and regenerative techniques to conserve and steward land on the campus site. This was made possible by the strong multi-disciplinary working relationship between the local team working on the ground and MASS Design.

The curriculum integrates practical, hands-on skills with theory to create a network of Rwandan farmers who can leave the campus and bring their knowledge of indigenous, resilience-building techniques and the associated worldview across the nation.

SOURCES

ASLA. “Rwanda Institute for Conservation Agriculture.” 2020 Professional Awards. https://www.asla.org/2020awards/397.html

Baraka, Eugene. “Rejection of African Indigenous Food: The Case of Rwanda.” Thesis presented at the University of Netherlands. 2021.

Delepierre, G. Les Regions Agricoles du Rwanda. Bulletin Agricole du Rwanda 8, no. 4 (1975): 216-225.

Eyong, Charles Takoyoh. Indigenous Knowledge and Sustainable Development in Africa: Case Study on Central Africa. Bonn, Germany: Center for Development Research, 2007.

Olson, Jennifer M. Rwanda Society-Environment Project Working Paper 2. Michigan State University Department of Geography, 1994.

Ndayambaje J D, Mukuralinda A , Njoki C, Niyitanga F, Bambe J C, Kinuthia R , Kuria A , Muthuri C. Trees for Food Security-2 Project: Rwanda Highlights. Canberra: World Agroforestry, 2021.

Taremwa, Nathan K., Damascene Gashumba, Anastase Butera and Thimmaiyah Ranganathan. “Climate Change Adaptation in Rwanda through Indigenous Knowledge Practice.” Journal of Social Sciences 46, no. 2 (2016): 165-175.

Transsolar. “Rwanda Institute for Conservation Agriculture RICA, Bugesera District, Eastern Province, Rwanda.” 2021. https://transsolar.com/projects/rwanda-institute-for-conservation-agriculture-rica