THE GREAT GREEN WALL

Overview

The Great Green Wall is a transnational afforestation initiative that utilizes agroforestry practices to counteract climate change related desertification across the African Sahel. The project, which was initially conceived in the 1950s, found international traction in 2002 as part of the United Nations Council on Combating Deforestation. Since 2002 the Great Green Wall has evolved from being “a line of trees from the east to the west through the Sahel . . . to that of a mosaic of interventions addressing the challenges facing the people in the Sahel and the Sahara” (FAO, 2009). The project — which has been officially underway since 2010 and is estimated to be about 15% complete — utilizes agroforestry techniques rooted in local practice and is managed by a coalition of local, regional, and international organizations.

Agroforestry

The Great Green Wall relies upon the involvement of local farmers and prioritizes the development of agroforestry practices that:

- Rejuvenate old agroforestry parklands through planting tree crops like cashew or through restoring natural species such as the shea nut (Vitellaria paradoxa).

- Protect and manage the natural regeneration of abandoned cropland and degraded non-farmland.

- Encourage and support the local protection and management of forests by local communities and forest-user groups.

- Use rainwater harvesting and other ecological agroforestry practices to restore dried out soil and cropland.

- Improve the management of livestock and grazing areas by pastoralists through the systematic protection and regeneration of trees and shrubs that are important sources of browse for livestock.

- Support sustainable intensification of rain-fed crop production through a combination of improved fertilizers and livestock.

Agencies, Organizations and Policymakers

African Union (AU)

Pan-African Agency of the Great Green Wall (PAGGW) est. 2010

Community of the Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD)

Great Green Wall Initiative of the Sahel (GGWSSI)

United Nations Council to Combat Desertification

FLEUVE 2014-2019 (Local Environmental Coalition for a Green Union)

Permanent Inter-State Committee for Drought Control in the Sahel

European Union

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

Global Environment Facility

United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification

International Union for Conservation of Nature

Sahara and Sahel Observatory

World Bank Group

African Forest Forum (AFF)

African Union Commission (AUC)

Association for the promotion of education and training abroad (APEFE)

Arab Maghreb Union (UMA)

Community of Saharan and Sahelian States (CEN-SAD)

Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)

Pan-African Agency of the Great Green Wall (PAGGW) est. 2010

Community of the Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD)

Great Green Wall Initiative of the Sahel (GGWSSI)

United Nations Council to Combat Desertification

FLEUVE 2014-2019 (Local Environmental Coalition for a Green Union)

Permanent Inter-State Committee for Drought Control in the Sahel

European Union

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

Global Environment Facility

United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification

International Union for Conservation of Nature

Sahara and Sahel Observatory

World Bank Group

African Forest Forum (AFF)

African Union Commission (AUC)

Association for the promotion of education and training abroad (APEFE)

Arab Maghreb Union (UMA)

Community of Saharan and Sahelian States (CEN-SAD)

Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)

European Union (EU)

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)

Global Mechanism of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (GM-UNCCD)

Intergovernmental Authority on Development in Eastern Africa (IGAD)

MDG Center for West and Central Africa (MDG-WCA)

Pan African Farmers Organization (PAFO)

Pan-African Agency of the Great Green Wall

Permanent Interstate Committee for Drought Control in the Sahel (CILSS)

Sahara and Sahel Observatory (OSS)

Secretariat of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD-Secretariat)

United Nations Development Programme – Drylands Development Center (UNDP-DDC)

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)

United Nations Environment Programme – World Conservation Monitoring Center (UNEP-WCMC)

Walloon Region of Belgium

Wallonie-Bruxelles International

World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF)

World Overview of Conservation Approaches and Technologies (WOCAT)

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)

Global Mechanism of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (GM-UNCCD)

Intergovernmental Authority on Development in Eastern Africa (IGAD)

MDG Center for West and Central Africa (MDG-WCA)

Pan African Farmers Organization (PAFO)

Pan-African Agency of the Great Green Wall

Permanent Interstate Committee for Drought Control in the Sahel (CILSS)

Sahara and Sahel Observatory (OSS)

Secretariat of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD-Secretariat)

United Nations Development Programme – Drylands Development Center (UNDP-DDC)

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)

United Nations Environment Programme – World Conservation Monitoring Center (UNEP-WCMC)

Walloon Region of Belgium

Wallonie-Bruxelles International

World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF)

World Overview of Conservation Approaches and Technologies (WOCAT)

Key Terms

INTRO

More than trees - a living landscape mosaic

The Great Green Wall is organized around small-scale community participation and aims to provide food security and community resilience across the Sahel region. Using regenerative planting and farming practices, a mosaic of diverse interventions enrich the soil and transform microclimates to provide better livelihoods for millions of people in an area which stretches nearly 5,000 miles across the African continent.

WHERE / WHO?

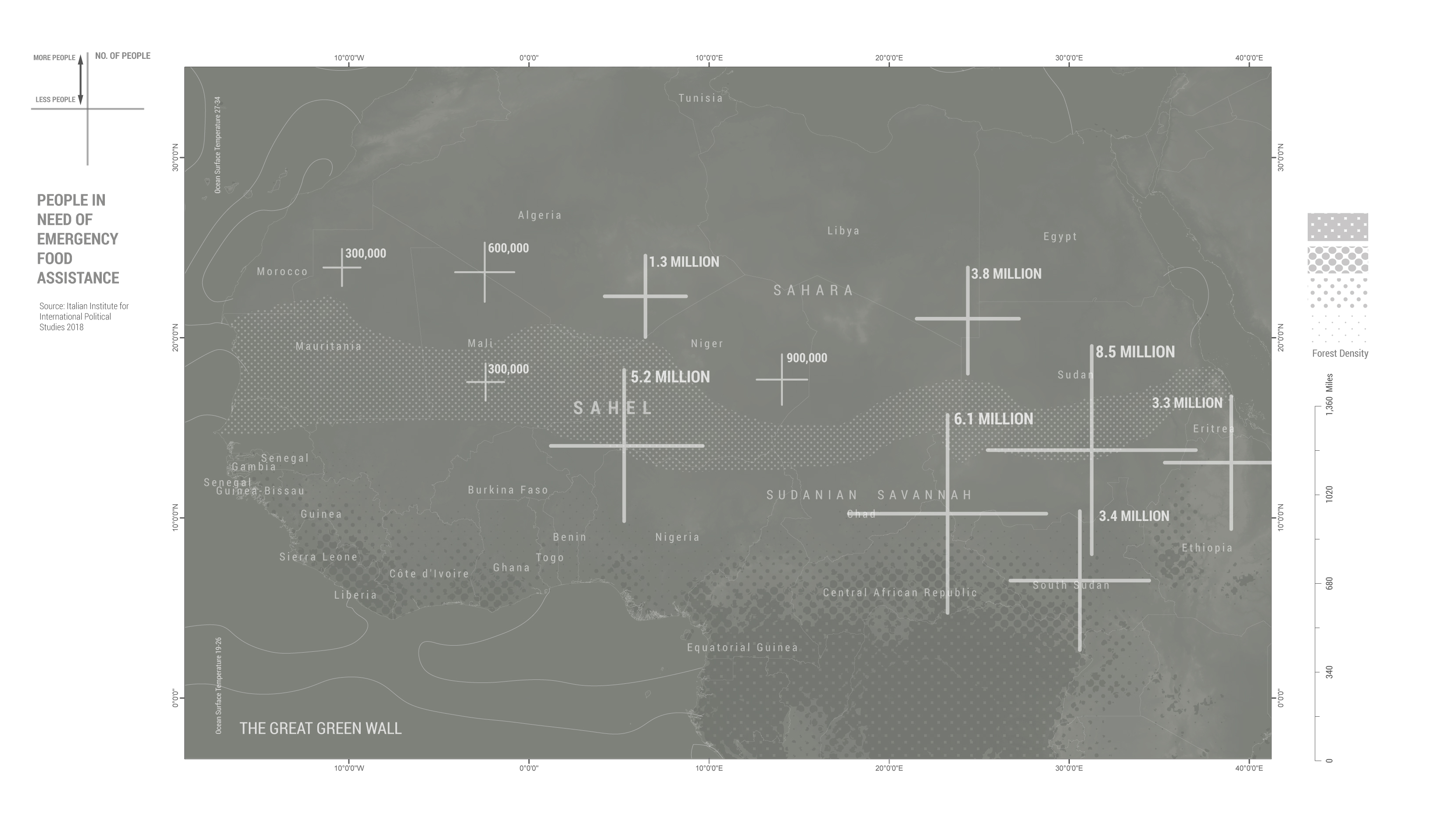

![Fig. 3. The Sahel is a transitional arid and semi-arid region between the Sahara to the north and the Sudanian Savannah to the south. Warming temperatures and decreased rainfall continue to exacerbate poor soil conditions across much of the region. The current iteration of the Great Green Wall is a mosaic of landscape interventions across the Sahel Region.]()

![Fig. 4. A gradient of Dry Subhumid to Hyperarid regions in Northern Africa. The Atlantic multidecadal oscillation (AMO) variability is linked to Sahel rainfall; when there is a cold AMO phase, there are extended droughts over the Sahel. Increasing greenhouse gasses raise the AMO, which leads to increasing rainfall. Aridity biomes adapted from: Niemeijer, David, Robin White and Grégoire de Kalbermatten. “Desertification Synthesis Ecosystems and Human Well-being.” (2005).]()

![Fig. 5. The Sahel is a transitional ecoregion of semi-arid grasslands, savannas, steppes, and thorn shrublands. Over time, sand has shifted - the Sahara is not taking over the Sahel, but it is fluctuating based on intercontinental trends.]()

![Fig. 6. The West African climate has shifted multiple times between humid optima and hyperarid since the end of the last glacial period, leading to massive migrations and the rise and fall of cities. Aridity and Migration Data: Coutros, Peter R. “A Fluid Past: Socio‐Hydrological Systems of the West African Sahel across the Long Durée.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water 6, no. 5 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1365. Maps and Images: Cyon, Nikolaj.Alkebu-lan 1260 AH Presentation. December 16, 2014. https://prezi.com/zqjrcx-uj7d_/alkebu-lan-1260-ah-presentation/ (accessed July 16, 2020)]()

![Fig. 7. Drought conditions contribute to food scarcity - a major problem facing the region which is expected to worsen as the population is predicted to double by 2050. Source: Corda, Tiziana. “A Tale of Two Related Plights: Climate Change and Humanitarian Crises in Africa.” ISPI. Italian Institute for International Political Studies, March 29, 2018. https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/tale-two-related-plights-climate-change-and-humanitarian-crises-africa-19964.]()

![Fig. 8. Famine and migration followed the droughts of the 1910s, 1940s, 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s with partial recovery from 1975-80. Increases in greenhouse gases around the world in the 1980s ended the Sahel drought period. The most recent drought occured in 2012. Image: FAO/Giulio Napolitano. Over the next decade, 50 million people may be displaced – the result of climate change and the depletion of natural resources. 2016. Color Photograph. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. From: FAO, http://www.fao.org/in-action/action-against-desertification/news-and-multimedia/photos/ni-]()

![Fig. 9. 1950’s portrait by Malian photographer Seydou Keita, known for his portraits of people and families taken at his studio in Mali’s capital. Image: Keita, Seydou. Untitled. 1952/1955. Photograph. IPM International Photo Marketing.]()

![Fig. 10. 1960’s portrait by Malian photographer Malick Sidibe, known for his photographs of popular culture in 1960’s Mali. Image: Sidibe, Malick.The whole family on a motorcycle. 1962, Gelatin Silver Print. 50 x 60cm. Courtesy of Fifty one Fine Art Photography.]()

![Fig. 11. 1970’s portrait by Burkinabe photographer Sanlé Sory. Sory lives and works in Bobo-Dioulasso and started photographing his community in 1960 - the year his country became independent. Image: Sory, Sanlé. Les noceurs de Banzon (Banzon’s swingers). 1972. Silver Gelatin Print. Copyright Sanlé Sory.]()

![Fig. 12. Contemporary Tuareg musicians Les Filles de Illilghadad, founded by Fatou Seidi in Illighadad, a village in Niger. They are one of many Tuareg musical groups who have raised awareness about the conflicts facing their communities. The Tuareg reside in multiple countries but don’t have a majority anywhere. Image: López, Álvaro. Les Filles de Illighadad (from left): Fatou Seidi Ghali, Fatimata Ahmadelher, Alamnou Akrouni and Abdoulaye Madassane. The Guardian. 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/aug/01/fatou-seidi-ghali-the-worlds-first-female-tuareg-guitarist.]() The Sahel Region

The Sahel Region

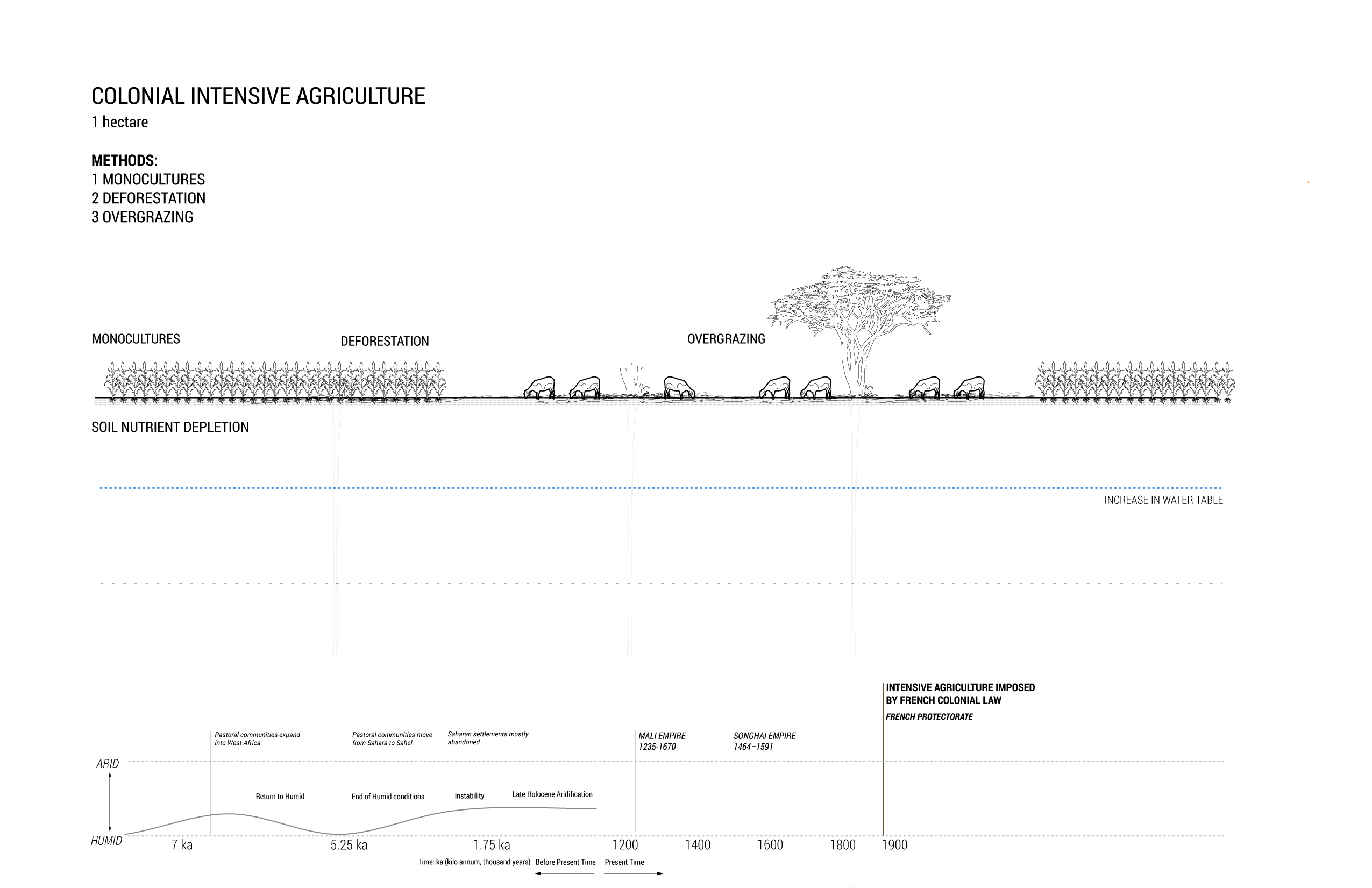

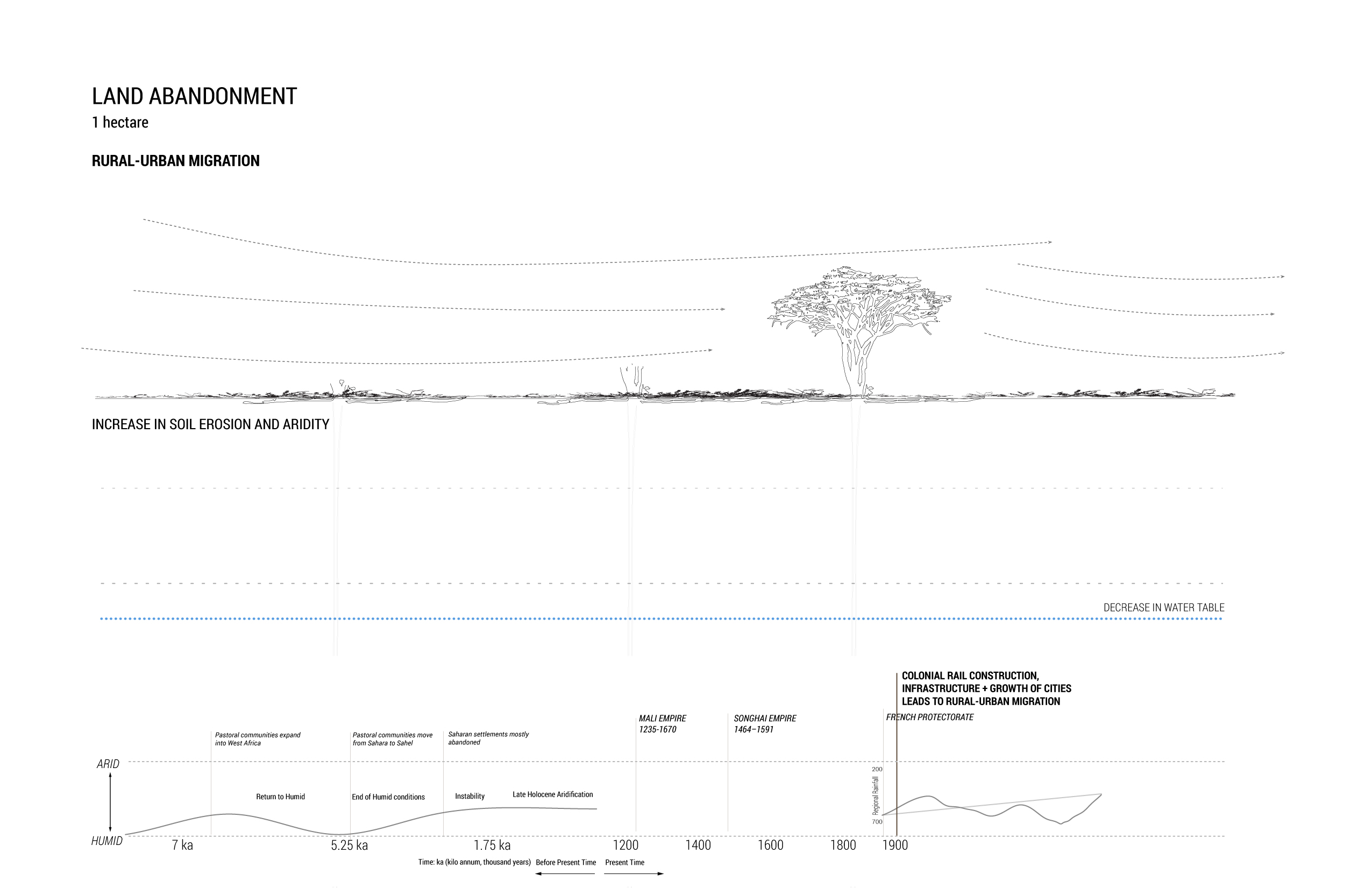

The Sahel is a transitional arid and semi-arid region between the Sahara to the north and the Sudanian Savannah to the south. Warming temperatures and decreased rainfall continue to exacerbate poor soil conditions across much of the region. In addition to being one of the most economically distressed regions of the globe, the area also faces persistent droughts. Both of these contemporary conditions stem, in part, from land policies imposed during the period of French Colonization that began in the late 1800’s and ended in 1958. The Sahel stretches across more than 20 countries and is home to seven major ethnic groups — the largest of which is the Hausa, the Songhai (dominant in the Western Sahel in 15th and 16th centuries), the Mossi who make up the majority in Burkina Faso, and the Tuareg who traditionally are nomadic cattle herders with no recognized homeland.

Process of Desertification

Desertification across the Sahel is a human-made process linked to global warming, increasing human population density, and the development of agrosilvopastoral activities in which water, soil, fauna, and flora are overused and not given enough time to recover.

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE GREAT GREEN WALL

Evolution of the Great Green Wall

Conceived in the 1950s by the English botanist Richard St. Barbe Baker, the idea of a Great Green Wall has evolved from a single line of trees stretching across northern Africa to a mosaic of agroforestry and anti-desertification interventions across 20 countries in the Sahel region. The ongoing evolution of the project is largely driven by individuals and organizations working on the ground in the region. The project operates within the purview of both international and local organizations and NGOs, from the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification to local NGOs like Réseau MARP (Participatory Rural Appraisal Network) in Burkina Faso.

TECHNIQUES - AGROFORESTRY + AFFORESTATION

Agroforestry

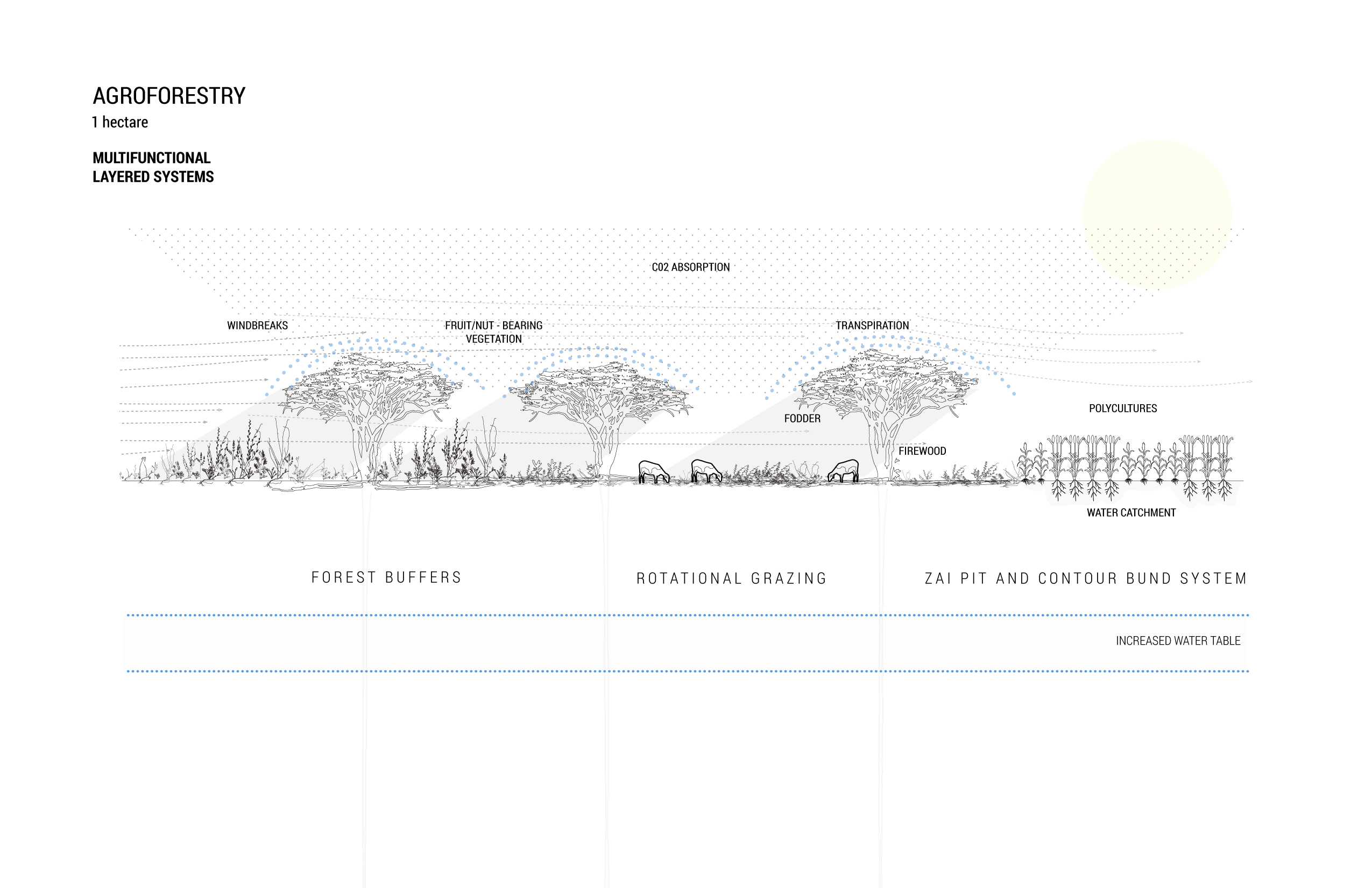

Agroforestry is a collective name for land-use systems and technologies where woody perennials (trees, shrubs, palms, bamboos, etc.) are deliberately used on the same land as agricultural crops and/or animals. Trees shade crops from overwhelming heat, act as windbreaks that protect young crops, and help the soil retain moisture. When tree leaves fall to the ground, they act as mulch, boosting soil fertility and providing fodder for livestock. Improvements to soil fertility and crop yield boost local incomes and transform the microclimate. Agrosilvopastoral systems are land use systems that include crops, forestry, and pastureland. These systems are found in drylands across the globe.

CASE STUDY - BURKINA FASO

Burkina Faso Case Study

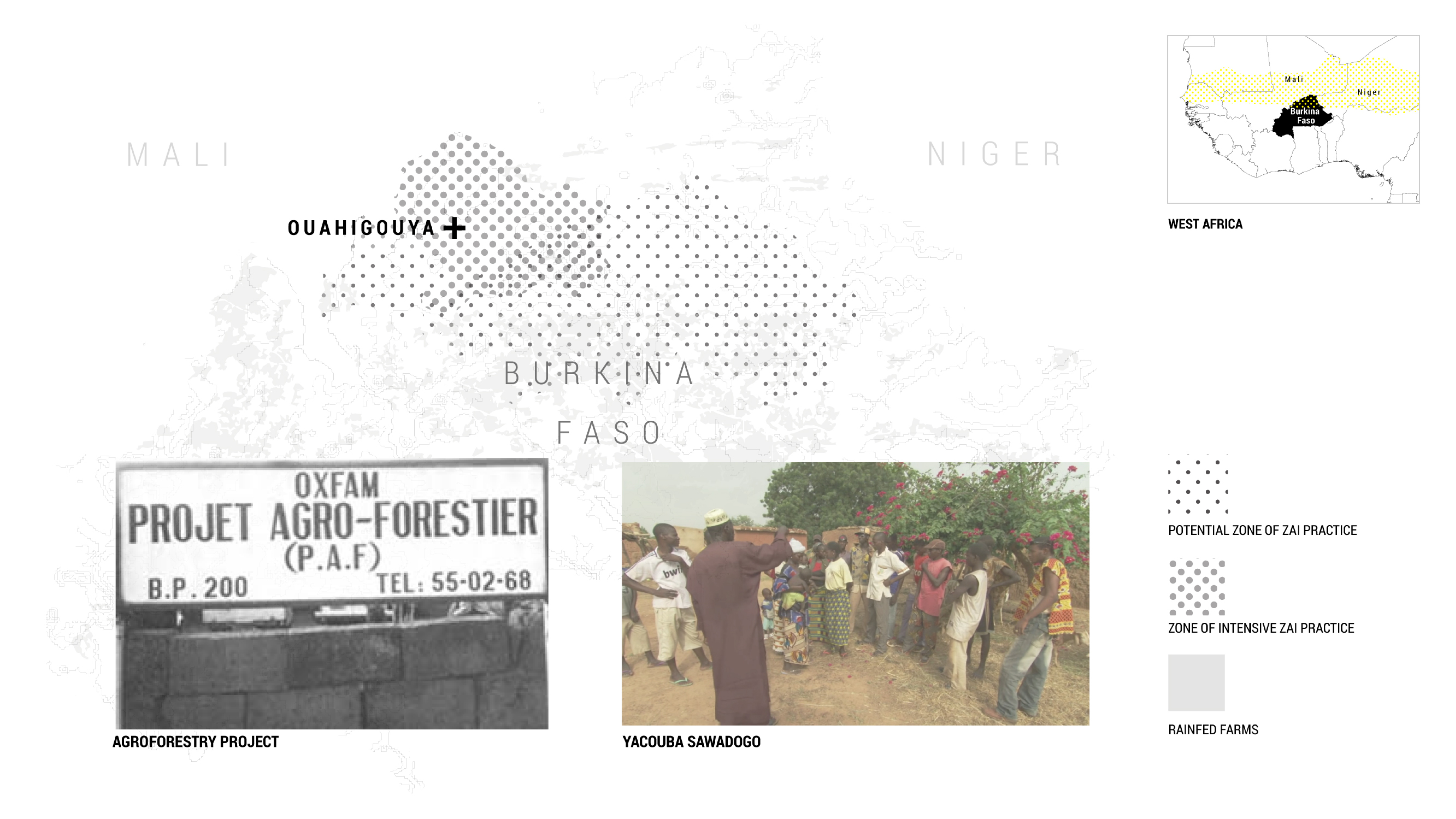

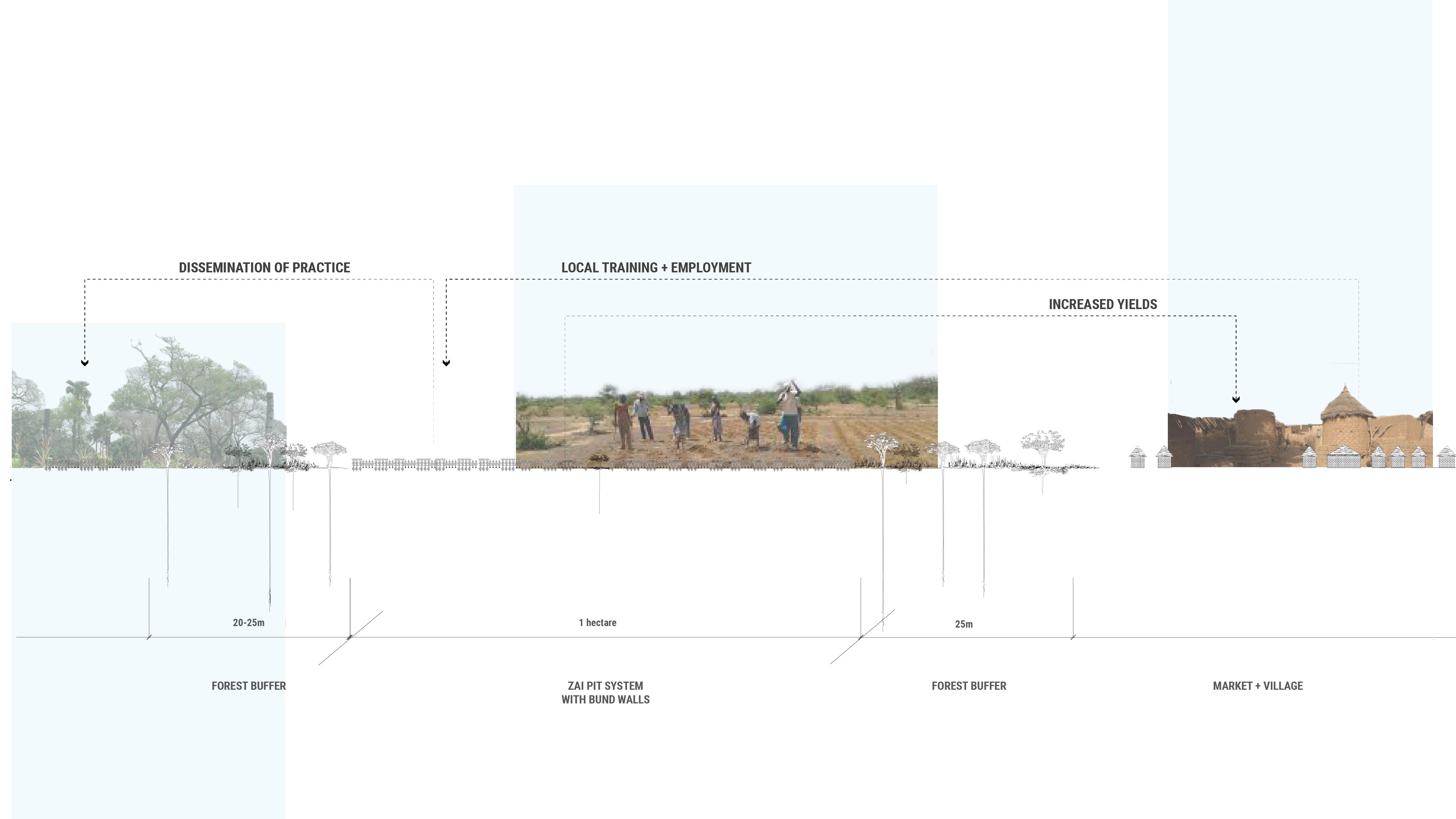

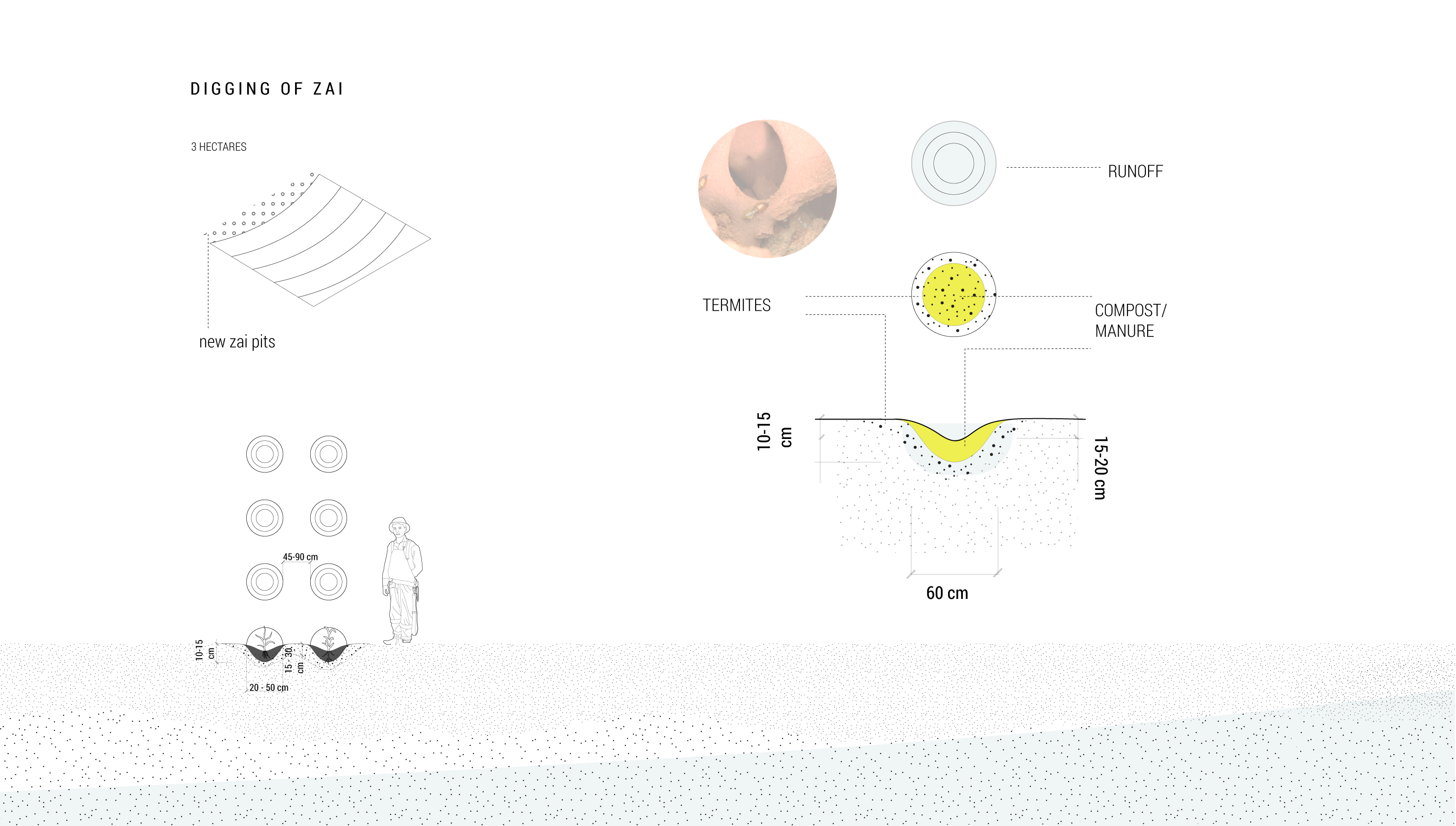

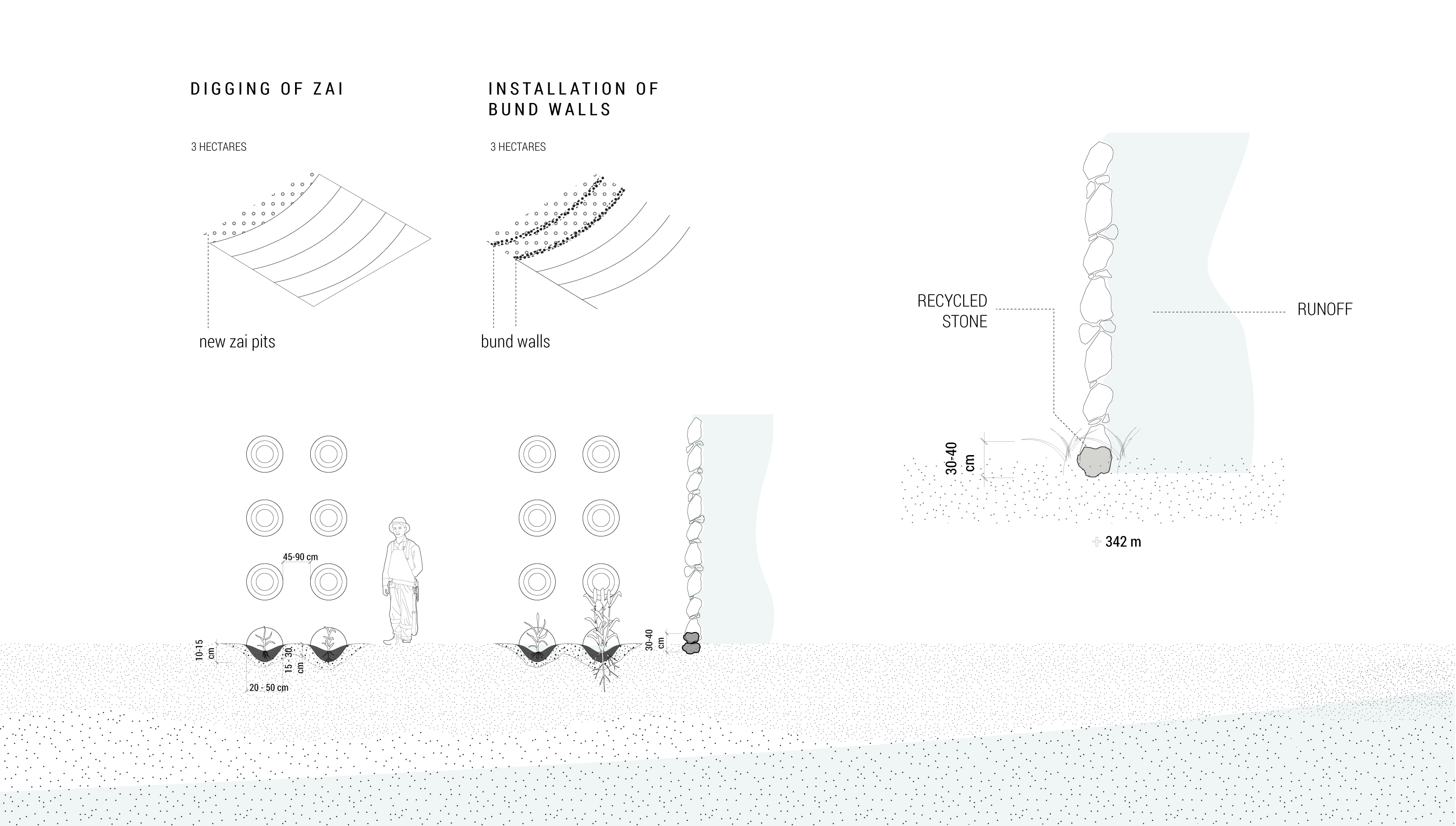

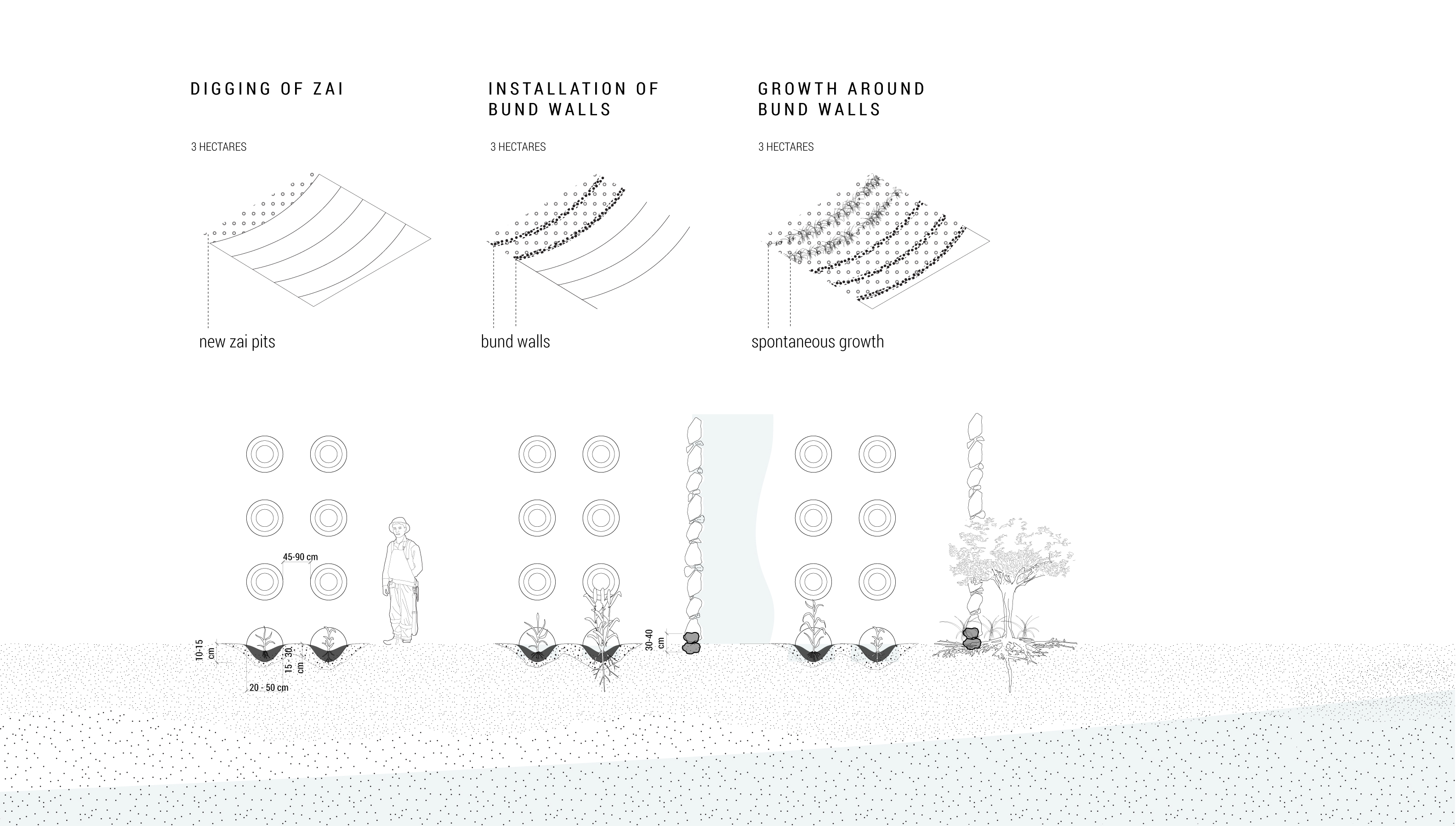

The implementation of the Great Green Wall varies by country and locale. In the 1980s, farmers helped shift the emphasis of Oxfam’s agroforestry project (PAF) in the Yatenga region in Burkina Faso by prioritizing food production rather than planting trees. The PAF project followed the defunct GERES project which was abandoned due to its failure to involve local residents. In Burkina Faso, a landlocked country in West Africa, the “Zai” pit technique that has been used for centuries in order to grow crops in the arid Sahel has become a prominent method in the construction of The Great Green Wall in northern Burkina Faso. Zai pits are small planting pits that measure 7 to 11 inches wide and 4 to 8 inches deep.

Sawadogo’s Zai Pit Methods

The farmer-innovator Yacouba Sawadogo adapted the traditional technique of Zai pit farming and combined them with PAF’s contour stone bunds to reduce runoff destruction of the Zai pit. Yacouba Sawadogo's Zai pit farming methods conserve water, build soil fertility, and have been shown to increase crop yields by up to 100%. Over a 7-10 year period, and following Sawadogo's guidance, farmers first dig Zai pits, adding compost or manure and termites to the beds in which they plant millet or sorghum. Second, farmers install low bund walls made of stone to capture water and seeds. In time, these bund walls are removed and reused to build additional bund walls as the crops grow. The line of stones becomes a line of plants which acts to slow the water further and additional tree and crop seeds caught in the runoff sprout at the upstream edge of the rocks. In the last stage of Zai pit farming, grasses are replaced by shrubs and trees, which further enrich the soil.

Impact

Today, 53% of farmers in the Yatenga Province of Burkina Faso have adopted Zai and stone contour bunds due to the combined efforts of Yacouba Sawadogo, the PAF, and other community members and organizations. But the Great Green Wall continues to face many challenges. Stone contours can only be built if there is a reliable supply of stones appropriate for construction; and the stone bunds can only support vegetation if there is adequate rainfall. Additionally, finding enough animal manure with sufficient quality to enrich the soil is difficult to attain. And not all farmers have the same resources to implement new techniques. Those with access to vehicles can transport stones to their farms more easily than those without, and the bulk of the building stone bunds falls disproportionately on women. Finally, competition arises between local groups attempting to practice sustainable farming and foreign NGOs eager to assist and implement their own agendas. The web of relationships at a range of scales can lead to overlap between the jurisdiction of NGOs, extension services, and the state.

REFERENCES

Kabore-Sawadogo, Seraphine, Korodjouma Ouattara, Mariam Balima, Issa Ouedraogo, San Traore, Maurice Savadogo and John Gowing. “Burkina Faso: A cradle of farm-scale technologies.” in Water Harvesting in Sub-Saharan Africa, eds. William Critchley and John Gowing.

Sawadogo, Hamado. “Using soil and water conservation techniques to rehabilitate degraded lands in northwestern Burkina Faso” in Sustainable Intensification: increasing productivity in African food and agricultural systems. Eds Jules Petty, Camilla Toulmin and Stella Williams. New York: Earthscan, 2011.

Batterbury, Simon. “Reviewed Works: Burkina Faso: New Life for the Sahel? By Robin Sharp”. African Affairs 95, no. 381 (1996): 599-604.

FAO. Great Green Wall for the Sahara and Sahel Initiative: The African Wall. Addis Ababa: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2009. http://www.fao.org/3/ap603e/ap603e.pdf

Reij, Chris, Gray Tappan and Melinda Smale. Agroenvironmental Transformation in the Sahel. International Food Policy Research Institute, 2009.

Wang, Shih-Yu and Robert R. Gillies. “Observed Changes in Sahel Rainfall, Circulations, African Easterly Waves and Atlantic Hurricanes since 1979.” International Journal of Geophysics (2011): 1-14.